Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols (102 page)

Read Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols Online

Authors: Kate Raphael

Tags: #Arts & Photography, #Architecture, #Buildings, #History, #Middle East, #Egypt, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Social Sciences, #Human Geography, #Building Types & Styles, #World, #Medieval, #Humanities

Another possibility is that the repairs were initiated by Baybars and only completed by Barka Khan, who took credit for the whole work and had his name entered on the inscription. According to Rabbat, Barka Khan acted in the same manner in Cairo: “He [Barka Khan] had his name attached to a number of structures in and around the citadel, but these had all been built by his father.”

233

As for the date, the Īlkhānid siege of 673/1275 appears to have caused more damage than the Mamluk sources care to reveal. Although the siege failed, the Īlkhānid army that assembled in front of al-Bīra’s walls numbered 30,000 men and 70 siege machines. The damage may ell have been considerable even though the siege lasted only nine days.

234

It seems likely that the repairs done by Barka Khan or/ and Baybars were due to damage caused during this siege.

The fortress of al-Bīra was constructed in a manner similar to that seen in the Ayyubid phase at ,

, ,

, and Mount Tabor: the towers were better built than the curtain walls. When the Mamluks rebuilt the curtain walls they did not change or improve the existing Ayyubid structure. The width of the curtain wall along the western side is approximately 2m while the walls of the southwest

and Mount Tabor: the towers were better built than the curtain walls. When the Mamluks rebuilt the curtain walls they did not change or improve the existing Ayyubid structure. The width of the curtain wall along the western side is approximately 2m while the walls of the southwest

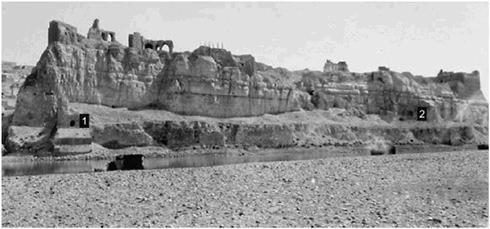

Figure 4.35

Al-Bīra, cliffs adorned with with curtain walls

corner tower (F) run between 2.5 and 3.3m. This however must be viewed with some reservations, since there are very few sections where the curtain wall is preserved and can be measured.

The plan followed a similar idea to that at , where there are only short stretches of curtain wall between the towers. The towers dominated the scene, while the curtain wall played a negligible part.

, where there are only short stretches of curtain wall between the towers. The towers dominated the scene, while the curtain wall played a negligible part.

Mighty towers

I could identify only two towers when I surveyed the site (towers F and E), though eight square towers can still be seen in the early twentieth-century photographs. What with the high vertical cliffs and the decision to make do with curtain walls of no great thickness, much of the defense depended on the towers. Both Ibn Shaddād and agree that the towers were built by Baybars.

agree that the towers were built by Baybars.

235

The masonry is of high quality. Pillars were inserted in the southeast tower in order to strengthen the wall structure (

Figure 4.36

); the same technique can be seen at the fortifications of Caesarea and the fortress of Shayzar.

236

Most of the towers had three floors, each pierced with arrow slits. In addition, archers could be positioned along the slanting base of tower F, where two levels of arrow slits can still be seen on the southern side (

Figure 4.37

). A

chemin de ronde

allowed archers to move easily from one position to the other.

237

Like Mamluk arrow slits elsewhere during this period, those of al-Bīra are spacious and have a large chamber that could accommodate a pair of archers. The only evidance of a machicoulis is in tower A.

Judging from the architectural evidence, and the inscription by found in tower F (see below) it seems he enlarged and renovated the entire tower in 1301.

found in tower F (see below) it seems he enlarged and renovated the entire tower in 1301.

The nā’ib’s quarters (?)

The large corner tower (F) contains the remains of a rather elaborate building resembling the plan of the governor’s residence found in several fortresses.

238

The center of the building is dominated by a square hall with a large room on either side.

239

A deep, elongated niche in the southern wall may have served as the . The central hall was covered by a dome decorated with a short inscription. The masonry is of the highest quality, consisting of smooth ashlars with simple decorative patterns created by using a fine mason’s comb. Since the dome has collapsed a substantial part of the building is covered in rubble (

. The central hall was covered by a dome decorated with a short inscription. The masonry is of the highest quality, consisting of smooth ashlars with simple decorative patterns created by using a fine mason’s comb. Since the dome has collapsed a substantial part of the building is covered in rubble (

Figure 4.38

).

The inscription found in this building (no longer

in situ

) and published by van Berchem gives a precise date, stating that it was renewed in 700/1301 by during his second reign (1298–1308). Since the sultan was 16 years old, the orders were issued by the ruling junta in

during his second reign (1298–1308). Since the sultan was 16 years old, the orders were issued by the ruling junta in name. This is clearly shown by the mention of the sultan’s helpers in the inscription. Both Creswell and Sinclair identified this building as a mosque.

name. This is clearly shown by the mention of the sultan’s helpers in the inscription. Both Creswell and Sinclair identified this building as a mosque.

240

However, residences of similar plans and dimensions were built at Najm, Shawbak and Karak; the latter has been ascribed to

Najm, Shawbak and Karak; the latter has been ascribed to and dates to the early fourteenth century.

and dates to the early fourteenth century.

241