Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols (31 page)

Read Muslim Fortresses in the Levant: Between Crusaders and Mongols Online

Authors: Kate Raphael

Tags: #Arts & Photography, #Architecture, #Buildings, #History, #Middle East, #Egypt, #Politics & Social Sciences, #Social Sciences, #Human Geography, #Building Types & Styles, #World, #Medieval, #Humanities

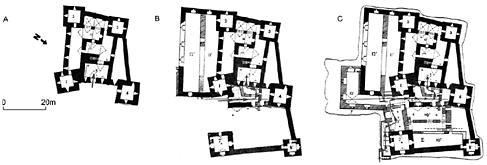

Figure 1.9

Postern at the northern wall of

Figure 1.10

Suggested stages in the development of the gate at

(1214–15) the main entrance was relocated to the corner tower in the east (

Figure 1.10c

). A corridor with a staircase led to a wide, arched gate with a portcullis. The external archway was decorated with a crude pattern of pigeons. The gate was given further protection by adding machicoulis allowing archers a vertical view down to the foot of the wall and moat. This is the only Ayyubid fortress of this group where the machicoulis can still be seen (

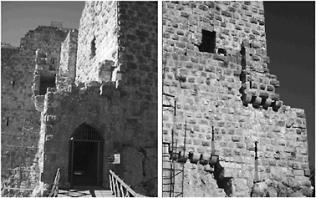

Figure 1.11

).

They resemble a closed hanging balcony projecting from the wall resting on stone corbels. From them archers could fire in a direct vertical line or drop molten lead, boiling oil, rocks and missiles.

166

They are small and cramped and were probably difficult to operate from.

Other than the main gate, the fortress did not have any posterns. As suggested above, this was possibly due to the relatively small size and compact plan, although an emergency exit would appear a necessity even in small fortresses.

The bent gateway was a simple construction. Although there are variations in size and form, the Ayyubids used this design and improvised upon it as they saw fit. The gate tower with the bent entrance as it appears in can be found in

can be found in

Figure 1.11 , machicolations above the main entrance belonging to the last building phase (1214–15)

, machicolations above the main entrance belonging to the last building phase (1214–15)

Frankish fortresses of both the twelfth and thirteenth centuries;

167

it continued to be used throughout the Mamluk period with relatively few innovations.

Curtain walls

The construction of all four fortresses on solid bedrock had two important advantages. The first was the almost absolute protection given to the walls and towers against enemy sappers. The second advantage was that there was no need to dig a foundation trench for the wall. The first stone course in and Mount Tabor was laid directly on the bedrock surface. This method of construction can still be seen today in Druze villages near

and Mount Tabor was laid directly on the bedrock surface. This method of construction can still be seen today in Druze villages near .

.

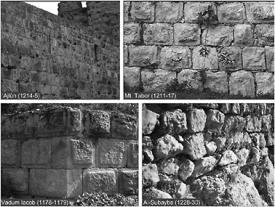

The basic structure of the curtain walls in Frankish and Ayyubid fortresses is similar. In both, the main part is constructed of a thick and wide core, traditionally consisting of stones neither dressed nor hewn. What holds the core together and gives solidity to the whole structure is a very generous amount of mortar. The core is faced with courses of stone blocks (

Figure 1.12

). The variations on this relatively straightforward building technique are surprisingly quite interesting. The core plays an extremely important role in the construction. If it is poorly composed the sapper’s work is made much easier. Once the stones of the outer wall are removed, breaking through the core would take little time and effort. In both Mount Tabor and the core was made of rocks and mortar with no apparent method and order. This technique, or rather lack of one, may have caused flaws within the core, considerably weakening it.

the core was made of rocks and mortar with no apparent method and order. This technique, or rather lack of one, may have caused flaws within the core, considerably weakening it.

Figure 1.12

Masonry along Ayyubid curtain walls and the Crusader curtain wall at Vadum Iacob

At the masonry along the curtain wall is of highest quality. It may well be that the small size of the fortress allowed the architect to spend a substantially higher percentage of his funds on finer quality masonry and better building techniques.

the masonry along the curtain wall is of highest quality. It may well be that the small size of the fortress allowed the architect to spend a substantially higher percentage of his funds on finer quality masonry and better building techniques.