Myanmar's Long Road to National Reconciliation (40 page)

Read Myanmar's Long Road to National Reconciliation Online

Authors: Trevor Wilson

In general, opposition strategies have focused on elite-level politics, rather than grass-roots democratization. However, both approaches are necessary — while neither is sufficient in itself. Change at the national level is urgently needed, but sustained democratic transition can only be achieved if accompanied by local participation and ‘development from below’.

13

More recently, an ICG report published in 2004 suggested that capacity-building for institutions outside the military is necessary — for example, for the civil service as well as for political and civil society groups and the business sector.

14

The report concludes that decades of hierarchical decision-making have stifled initiative and creativity at the same time as corruption and absenteeism have grown due to poor wages and working conditions. The report makes a number of pertinent recommendations including the following:

1. That restrictions limiting funding to narrowly defined humanitarian projects should be relaxed, in order to allow institution of broader sustainable livelihood programs with a longer timeframe;

2. That NGOs and agencies of the United Nations (UN) should collaborate more effectively and use their comparative advantage to greater effect;

3. That human rights and development protection agencies should cooperate more;

4. That international agencies should not “crowd out” or impede the development of local networks.

15

For these recommendations to be effective, it is essential that long-term development strategies be adopted and that investment in the capacities of both local groups and individuals through the delivery of more focused humanitarian assistance be promoted.

The earlier ICG report quotes Aung San Suu Kyi on linking development assistance to empowerment: “It is not enough merely to provide the poor with material assistance. They have to be sufficiently empowered to change their perception of themselves as helpless and ineffectual in an uncaring world.” The report goes on to point out that in practice this requires introducing democratic organizational structures into community development work and encouraging creative and independent thinking.

16

The notion that formal political change is a pre-requisite for all other change should be questioned. The case for “bottom-up” civil society growth is rapidly gaining credence. Paolo Freire reminds us that:

This then is the humanistic and historical task of the oppressed: to liberate themselves and their oppressors as well. The oppressors, who oppress, exploit, and rape by virtue of their power, cannot find in their power the strength to liberate either the oppressed or themselves. Only power that springs from the weakness of the oppressed will be sufficiently strong enough to free both.

17

Empowerment of all people, not simply reform of formal government structures, is necessary and whilst it would be naïve to suggest that civil society can grow unimpeded by formal government mechanisms of control, it will be shown quite clearly in the following section that distinct possibilities exist and that substantial steps have already been taken to that end.

Without going into a detailed typology of NGOs in Burma/Myanmar, some general distinctions can be made. There are, broadly speaking, four types of NGO: International NGOs;

• Government-sponsored NGOs (sometimes referred to as GONGOs), such as the Myanmar Maternal and Child Welfare Association and the more politically-oriented Union Solidarity Development Association. These should not be seen as civil society organizations;

• Local NGOs. Many of these have a religious affiliation, and there are also some that, although they have links with government departments (for example, the Myanmar Anti-Narcotics Association), do have more autonomy than the GONGOs;

• Small community-based organizations that cover a range of local functions such as organizing funerals and festivals, of which there are an amazing number in the country, about 214,000, according to David Steinberg.

18

This paper will deal primarily with international NGOs and the more established local NGOs.

There has been some debate about what constitutes a local NGO in Burma/ Myanmar. A recent publication,

Directory of Local Non-Government Organizations in Myanmar, March 2004

listed sixty-two local NGOs.

19

In order to be included in the directory, these groups had to meet a certain number of criteria, including having an office in Yangon, being non-profit, voluntary, independent, self-governing, socially accountable, human-welfare oriented, acting as an intermediary, socially progressive and having clear leadership. Funding for the compilation of this directory was provided by Save the Children UK, Oxfam Great Britain, and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Myanmar. Limitations of the funding meant that only NGOs with offices in Yangon could be surveyed, so this does not by any means represent the entirety of organizations in the country.

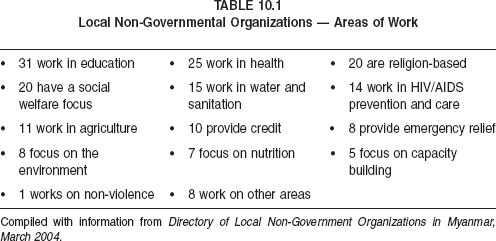

Table 10.1

shows the numbers of local NGOs that work in various areas.

While most organizations are small, one or more are present in all states and divisions. Sixty-four work in Yangon, the greatest number, whilst the smallest number of local NGOs in a State or Division is three, in Tanintharyi Division in the south. The majority have some religious affiliation, although groups such as the Myanmar Medical Association (MMA) and the Myanmar Literary Resource Centre are also represented. The goals of these organization cover a wide and varied ground, from providing drinking water for people at pagodas, monasteries, and other places to contributing to the “development of the Myanmar forest resources and natural environment, and entailing such statements as “transforming Myanmar into a learning society and develop human resources through non-formal education”, and “bringing about a higher health standard for everyone through high-standard effective quality nursing”. Some local NGOs are relatively small and cater for a specific number of beneficiaries, as, for example, some of the orphanage programs, while others, such as the MMA, have a country-wide affiliation with thousands of members.

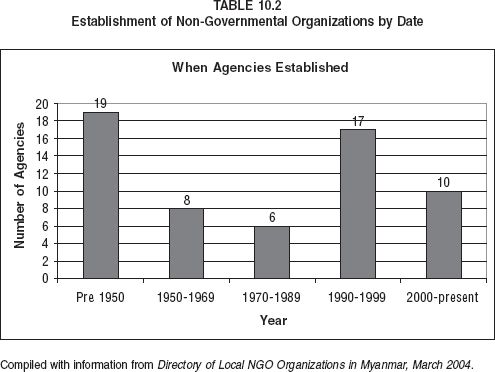

Table 10.2

shows the number of local NGOs established at different periods, and although a number date from before the 1950s, a marked growth has occurred over the past fourteen years.

Apart from the International Committee of the Red Cross, about forty international NGOs are working inside Burma/Myanmar.

20

Some have been operational for over ten years, while the majority have entered the country within the past five years (since the publication of the article by Marc Purcell mentioned above). Their focus, both in terms of sectoral as well as geographic area, is varied, ranging from the more specific health-related programs run by the Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) alliance members to the broad-based community development approach followed by organizations such as World Vision. Whilst HIV/AIDS is a key component of many organizations’ programs, most other development sectors are addressed: re-forestation, disaster relief, vocational training, street children and child rights, agricultural development, micro-credit, anti-trafficking, water and sanitation are just some of the ever-increasing areas covered.

International NGOs themselves can be seen to offer a number of concrete contributions to the development of civil society in Burma/Myanmar. While this paper will focus on two international NGOs only, it is important to identify some of the more common elements of international NGO programs. Though they relate primarily to the first and second generation of Korten’s NGO strategies, they do, nonetheless, relate directly to civil society building.

1. First, most international NGOs have a community presence and rely on the commitment of volunteers to implement parts of their programs. These volunteers often form into well-established groups that play a primary role in the delivery of humanitarian aid. Often, they act as the interface between the international NGO and the community.

2. Second, international NGOs invest in the development of their national staff by fostering both technical and leadership skills. Although this training is insufficient to meet all the needs, a small but growing cadre of development professionals is being created. As a result, the work of international NGOs is increasingly being directed by national staff who are gaining increasing confidence in the identification, design, implementation, and evaluation of development projects. While only one international NGO is headed by a Myanmar national, all have nationals in senior management positions.

3. Third, community mobilization around specific issues, whether it be AIDS or water and sanitation or micro-credit, is a common strategy followed by international NGOs. This has brought about an understanding within communities of the importance of participatory democratic decision-making processes and lays the foundation for the greater involvement of civil society at a local level.

4. Fourth, working at a community level automatically puts international NGOs into close contact not only with local authorities but also with government-sanctioned NGOs such as the Myanmar Maternal and Child Welfare Association (MMCWA), USDA, and others. This kind of local-level interaction does have the potential to create meaningful dialogue around development issues. Another element in this interaction is that many international NGO programs work quite closely with government ministry officials at the local level, particularly with officials of the Ministry of Health in relation to work on HIV.

5. Fifth, advocacy before the United Nations is another valuable, though perhaps under-utilized, strength of international NGOs, since, except in a few instances, the United Nations does not work directly at community level. International NGOs have the ability to advocate with, and on behalf of, community groups and individuals when approaches on development and humanitarian issues are made to the UN. To a considerable extent UN agencies rely on international NGOs having this direct access to communities. In the absence of any consistent and structured means through which communities or NGOs can advocate to the government, advocating to the UN as an intermediary is at least a step in the right direction.

The following section will look at aspects of programs being implemented by a number of international NGOs, primarily World Vision Myanmar and the Burnet Institute. These two organizations have totally different responses to their role as development organizations in the country and therefore provide an interesting contrast to the broader analysis of the role

of international NGOs in the building of civil society. The information in these sections is based on the author’s personal experience in both organizations.

World Vision Myanmar has been operating in Burma/Myanmar since the early 1990s. Beginning with some very small health and HIV-related programs, it now has one of the largest international NGO programs in the country, with a budget of some US$5 million per year and a staff of over 230 people. World Vision Myanmar operates in most states and divisions, and covers a broad range of sectors, from relief to HIV prevention and care, micro-enterprise development, and work with street children. The mainstay of World Vision’s presence in the country has become the Area Development Program (ADP) — broad-based community development programs that are funded primarily through the child sponsorship mechanism and that focus on a township area (generally a population of around 70,000 people). ADPs generally have a mix of activities, in sectors such as health, education, income generation and micro-credit schemes, water and sanitation, programs for the disabled, skills-training activities, anti-trafficking activities, HIV prevention and care, and social enhancement programs (with a focus on addressing domestic violence), and follow a long-term development plan that may cover up to fifteen years. Both ADPs and the more focused sectoral initiatives (such as street children) follow a participative approach in the development and implementation of interventions.

21