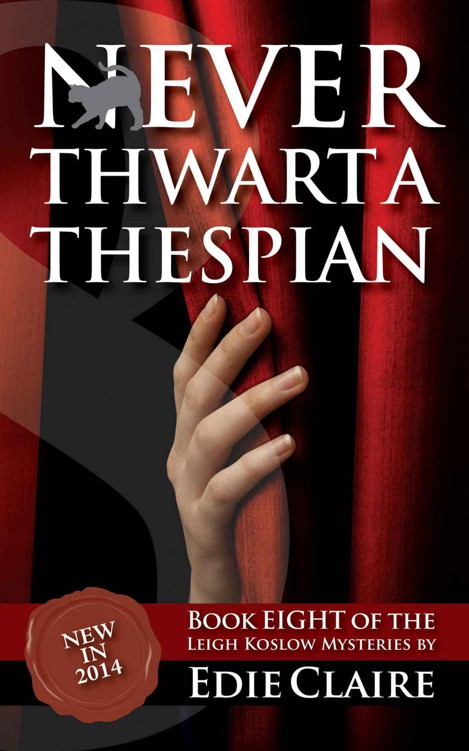

Never Thwart a Thespian: Volume 8 (Leigh Koslow Mystery Series)

Read Never Thwart a Thespian: Volume 8 (Leigh Koslow Mystery Series) Online

Authors: Edie Claire

Tags: #thespian, #family secrets, #family, #show, #funny mystery, #women sleuths, #plays, #amateur sleuth, #acting, #cozy mystery, #cats, #pets, #dogs, #daughters, #series mystery, #theater, #mystery series, #stage, #animals, #mothers, #drama, #humor, #veterinarian, #corgi, #female sleuth

NEVER THWART A THESPIAN

Copyright © 2014 by Edie Claire

This book is a work of fiction. The names, characters, places, and incidents are products of the writer's imagination or have been used fictitiously and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to persons, living or dead, actual events, locales or organizations is entirely coincidental.

All Rights Are Reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the author.

Dedication

For Jami, Jan, Justin, Kim, Mark, Rick, Sarah, Trina, and

all my other beloved acting buds with AOG.

It was the best of times.

Period.

Chapter 1

“Isn’t it the most glorious place you’ve ever seen?!” Bess crowed, spreading her arms wide above her head and nearly toppling backwards off the crumbling concrete steps in the process. “Just look at it!”

Leigh pulled back the hand she’d flung out in case her aunt actually did topple backward, then looked. Bess’s ability to view the decrepit monstrosity of a building before them through rose-colored glasses came as no surprise. The fact that the lenses of her current pair of 80s-vintage plastic sunglasses were, in fact, tinted red was pure coincidence.

“I’m looking,” Leigh replied drily.

Bess turned to her niece with a glare. “No negative Nellies!” she admonished. “I have your mother for that. You have to open up your mind to the

possibilities!”

Leigh took another look. The sight was by no means new to her; growing up in West View, a suburb north of Pittsburgh, she had passed by the red brick building on the borough’s main drag thousands of times. But she couldn’t remember ever being impressed. Even during her childhood, its bizarre facade had raised questioning eyebrows. The structure had originally been built as a church, which would explain the large, square tower to the right of the double front doors. According to Leigh’s mother Frances, the top of the tower had once been edged with brick and mortar crenelations surrounding a giant wooden steeple and metal cross. After the building was sold to a fraternal order, however, a few of their more boisterous members had tried to remove the steeple with a wrecking ball while “under the influence,” knocking off not only the spire but a good bit of the surrounding masonry besides. The result was a tower that looked like it had a giant mouth open to the sky — a mouth with half its teeth knocked out.

Leigh struggled for an optimistic comment. “Maybe it looks better inside?”

Bess’s lips twisted ruefully. “Not really,” she admitted. “But it will when we’re done with it!”

Leigh tensed. “We?”

“Why, of course,” Bess replied, leading her niece up the remaining steps toward the front doors. “You didn’t think I would be so crass as to cut you out of such an important family project, did you?”

Leigh’s steps halted. “You do realize that putting the words ‘family’ and ‘project’ in the same sentence makes me want to run screaming, right?”

Bess merely chortled. “It’s going to be marvelous!” She inserted a key into the door lock, struggled with the mechanism a moment, then pushed open the creaking wooden door. “After you, kiddo,” she insisted, stepping back and gesturing Leigh inside.

Leigh complied. Her aunt’s affectionate use of the term “kiddo” had bothered her when she was a teenager, but now that she was on the gray side of forty, she took it as a compliment. She stepped through the doorway into what must once have been a church vestibule. A few ancient-looking metal coat racks were crammed along the far wall, while other doorways led left and right. The scuffed black and white tile floor was littered with shards of plaster and curls of paint that had peeled from the butter-yellow ceiling and walls.

Leigh stepped over the debris and moved hesitantly toward the right doorway. “Shouldn’t we be wearing hardhats or something?”

“Oh, piffle!” Bess retorted, pushing her sunglasses to the top of her head and moving on into the next room. “It may look a bit shabby at the moment, but it’s not like it’s been

condemned

or anything! If it had been, I could never have convinced Gordon to buy it — not that I didn’t have to sell that miser half my soul in any event.” She let out a huff. “Two different inspectors agreed that despite its appearance, the building

is

structurally sound. It just needs a little TLC; that’s all.”

Leigh hid a smile. From what she knew of Gordon Applegate, who happened to be one of her husband Warren’s financial management clients, the man was no miser. He was one of Pittsburgh’s most generous philanthropists.

He was also — ordinarily — not an idiot.

“I’ve been meaning to ask,” Leigh said tentatively, stepping into the old sanctuary after her aunt while keeping a watchful eye toward the ceiling for falling beams. “How

did

you get Mr. Applegate to invest in this little venture?”

Bess gave a dismissive flick of her left hand while her right hand searched for a light switch. “The man’s got more money than God and he’s had the hots for me ever since I played Gertrude in Hamlet. Oh, here we are. Ta-da!”

The lighting in the cavernous room changed from eerily dim to slightly less dim. Leigh took a couple steps forward and looked around. The space was as wide as it was deep, with large windows on either side and a raised platform at the opposite end. Behind the platform was an empty odd-shaped area bounded by half-walls that Leigh suspected had once housed a choir loft and organ pipes. Doors on either side of the former chancel led back into the rest of the building. The high, arched ceiling was bedecked with ancient rotating fans, a few of which were missing blades. The entire room was coated with a thick layer of dust and the worn brown carpet beneath their feet was beyond filthy. All in all, Leigh was pleasantly surprised. Knowing her Aunt Bess, the room could just as easily have contained a disassembled carnival ride or an elephant graveyard.

“Interesting,” Leigh conceded. “How old is it?”

“Going on a hundred years,” Bess replied proudly, her eyes twinkling. “The cornerstone was laid in 1915. By an independent Baptist congregation, I believe.”

Leigh walked further out into the room. Her gaze rested on the area behind the chancel, and a queer prickling started at the base of her neck. She stopped moving.

“Unfortunately, the people who built it didn’t stay here very long,” Bess continued. “It was owned by several different congregations, but all of them seemed to have trouble meeting the mortgage. I barely remember, when I was little, these windows having stained glass in them. There was a particularly pretty one out over the front doors — it showed the women at the empty tomb on Easter morning. But all the stained glass was removed and sold ages ago.”

At the word “tomb,” a wave of cold slid down Leigh’s spine. Her shoulders shivered. What was wrong with her?

“The last congregation that owned it put on the classroom addition in the back — that was in 1961,” Bess explained. “I bet that decision made for some lively church meetings, because they’d hardly used it two years before the loan went into default—” she broke off her lecture and took a step closer to Leigh. “What’s up, kiddo? You feeling all right?”

“I’m fine,” Leigh insisted, trying to make it the truth. “I just got a weird vibe or something.” She gave herself a shake and looked around again. It was just an empty room. “After the last church defaulted, is that when the Narwhals bought it?”

Bess chuckled. “Oh, you remember them, do you?”

“Their sign was hard to miss,” Leigh answered, remembering the giant wooden plaque that had occupied the front-window space throughout most of her own childhood. The Fraternal Order of the Narwhal, a group of businessmen her normally charitable father had once derided as “morons of a feather, flocking together,” had commissioned a local painter to immortalize their mascot, a medium-sized species of whale with a single horn sprouting from its forehead. The result was a freakish cartoon that Leigh and her cousin Cara had argued bitterly over during their elementary days. Cara had been certain that the painting showed a volcano spewing lava — Leigh thought it looked like chocolate pudding with a spoon sticking out.

“Ah, yes,” Bess agreed. “The Narwhals. Bunch of puffed-up dandies, pretending to be entrepreneurs. ‘Successful local merchants,’ indeed. They wound up defaulting just like everyone else! But to answer your question, no, they weren’t the first fraternal order to buy this place. That would be the Adders, back in the sixties. They were even crazier — used to conduct meetings wearing rubber snakes around their necks.” She gave an exaggerated shudder that jiggled her generous curves. “I dated one of them once. Lord help me, I’d have been better off with the snake.”

Leigh grinned. Her thrice-married aunt’s exploits with the opposite sex were legendary. Where reality ended and legend began was anyone’s guess, but Leigh knew better than to underestimate. “So they were the ones who got drunk and knocked off the steeple?”

“Bingo!” Bess said cheerfully, stepping up onto the platform. She turned around and faced an imaginary audience, lifting her hands to either side. “Thank you. Thank you all so much!” She moved her hands over her heart; her eyes filled with actual tears. “It’s true. I always believed in this place. And now, tonight, in your presence, the dreams of the North Boros Thespian Society have finally been realized. After twenty years of rented gymnasiums, barns, school auditoriums, and church basements, at long last we have our very own dedicated theater extraordinaire! Bless you. Bless you all!” She blew a kiss to the audience, then with a sweeping flourish took a bow so low and so dramatic she wound up collapsed on one knee, emotionally spent.

Leigh applauded, throwing in a whistle for good measure. Her aunt didn’t move. “Um… Aunt Bess?” she asked after a moment.

“Yes?” Bess answered, her face still to the floor.

“You can’t get up again, can you?”

“Not a chance, kiddo.”

Leigh stepped onto the chancel and gave her aunt a hand. As Bess regained her footing, Leigh glanced around the empty choir loft and organ pipe area with a frown. What

was

it about the place that creeped her out so much? “You really think you can turn this building into a theater?” she asked skeptically.

“Of course!” Bess declared, affronted. “It’s the perfect space. All we need to do is clean it up a little. We may not even have to rent chairs! There are loads of them in the basement, left over from when the place was a banquet hall. The society already owns some basic lighting equipment and flats and curtains and such. Getting everything ready for opening night in eight days won’t be easy, but it’s definitely doable!”

Leigh whirled to face her aunt. “Eight days? Opening night? Are you kidding me?” The room might not be filled with rotting elephant carcasses, but every possible surface was choked with dust, peeling paint littered the filthy carpet like snow, and she was pretty sure the spots on the choir railing behind her were bat guano. “You can’t get a show together in eight days

and

get this place suitable for the public!”

“I don’t see why not,” Bess countered. “The cast has been rehearsing for weeks already. All they need is a venue!”

Leigh started to get the picture. “So you’ve been planning all this for a while now.”

Bess smirked. “My dear, I’ve had my eye on this building for a

decade.

I bit my fingernails to the bone waiting for the borough to get possession of it and get it to a sheriff’s sale after that hustler Marconi took off and left it to rot. Blast that man… so many wasted years!”

Leigh searched her memory for the reference. “Oh, you mean the guy who wanted to turn it into a strip club?”

Bess’s expression soured. “That’s him.”

Leigh tried not to laugh. She remembered all too well the degree of apoplexy her mother had suffered upon learning that a “gentleman’s club” was moving smack dab into the middle of their beloved and heretofore perfectly Godly hometown. Frances Koslow had mobilized every women’s and/or religious organization in the borough (including both the Girl Scouts and the Indian Princesses) to protest against it, leaving no yard without a sign, no business without a publicly visible statement of support for the cause (lest their customer traffic mysteriously decline), and no zoning board member with a good night’s sleep until the necessary permit was denied. The fact that Frances’s twin sister Lydie, Cara’s mother, had joined the crusade was not surprising, since the two were always supportive of each other. But Leigh had been puzzled at the zeal shown by her Aunt Bess, who rather than being one to jump onto her younger sister’s moral high horse, usually enjoyed knocking Frances off of it.

“So

that’s

why you joined the ‘West View Citizens Against Indecency and Moral Turpitude!’” Leigh cried.

Bess’s lips pursed. “Let’s just say sacrifices were made.”

Leigh grinned. “I hope the North Boros Thespian Society appreciates you.”

Bess smiled slyly. “Oh, they will. We’ll get this theater yet, don’t you worry!”