Notebooks (26 page)

Authors: Leonardo da Vinci,Irma Anne Richter,Thereza Wells

Tags: #History, #Fiction, #General, #European, #Art, #Renaissance, #Leonardo;, #Leonardo, #da Vinci;, #1452-1519, #Individual artists, #Art Monographs, #Drawing By Individual Artists, #Notebooks; sketchbooks; etc, #Individual Artist, #History - Renaissance, #Renaissance art, #Individual Painters - Renaissance, #Drawing & drawings, #Drawing, #Techniques - Drawing, #Individual Artists - General, #Individual artists; art monographs, #Art & Art Instruction, #Techniques

All the surfaces of solid bodies turned towards the sun or towards the atmosphere illumined by the sun, become clothed and dyed by the light of the sun or of the atmosphere.

Every solid body is surrounded and clothed with light and darkness. You will get only a poor perception of the details of a body when the part that you see is all in shadow, or all illumined.

The distance between the eye and the bodies determines how much the part that is illumined increases and that in shadow diminishes.

The shape of a body cannot be accurately perceived when it is bounded by a colour similar to itself, and the eye is between the part in light and that in shadow.

67

67

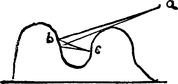

What portion of a coloured surface ought in reason to be the most intense? If

a

is light and

b

illuminated by it in a direct line, then

c

on which the light cannot strike is light only by reflection from

b

, which let us say is red. Then the light reflected from this red surface will tinge the surface at

c

with red. And if

c

is red also it will appear much more intense than

b

; and if it were yellow you would see there a colour between red and yellow.

58

a

is light and

b

illuminated by it in a direct line, then

c

on which the light cannot strike is light only by reflection from

b

, which let us say is red. Then the light reflected from this red surface will tinge the surface at

c

with red. And if

c

is red also it will appear much more intense than

b

; and if it were yellow you would see there a colour between red and yellow.

58

The surface of an object partakes of the colour of the light which illuminates it, and of the colour of the air that is interposed between the eye and this object, that is to say of the colour of the transparent medium interposed between the object and the eye.

68

68

Colours seen in shadow will reveal more or less of their natural beauty in proportion as they are in fainter or deeper shadow. But colours seen in a luminous space will reveal greater beauty in proportion as the light is more intense.

Colours seen in shadow will display less variety in proportion as the shadows in which they lie are deeper. And evidence of this is to be had by looking from an open space through the doorways of dark churches, where the pictures painted in various colours all appear covered by darkness. Therefore at a considerable distance all shadows of different colours will appear of the same darkness. In an object in light and shade the light side show its true colour.

69

69

Of the nature of contrasts

Black garments make the flesh tints of the representations of human beings whiter than they are, and white garments make the flesh tints dark, and yellow garments make them seem coloured, while red garments show them pale.

70

70

Of the juxtaposition of one colour next to another

so that one sets off the other

so that one sets off the other

If you wish the proximity of one colour to make attractive another which it borders, observe that rule which is seen in the rays of the sun that compose the rainbow, otherwise called the Iris. Its colours are caused by the motion of the rain, because each little drop changes in the course of its descent into each one of the colours of that rainbow, as will be set forth in the proper place.

71

71

Of secondary colours produced by mixing other colours

The simple colours are six, of which the first is white, although some philosophers do not accept white or black in the number of colours, because one is the cause of colours and the other is the absence of them. Yet, because painters cannot do without them, we include them in their number, and say that in this order white is the first among the simple, and yellow is second, green the third, blue is the fourth, red is the fifth, and black is the sixth.

White we shall put down for the light, without which no colour can be seen, yellow for the Earth, green for the Water, blue for the Air, red for Fire, and black for the darknesses which are above the element of Fire; for there is no matter of any density there, which the rays of the sun must penetrate, and, in consequence, illuminate. If you wish briefly to see all the varieties of composed colours, take panes of coloured glass and look through them at all the colours of the country, which are seen beyond them. Then you will see that the colours of things seen beyond the glasses are all mixed with the colour of the glass and you will see which colour is strengthened or weakened by this mixture. For example, if the glass is yellow in colour, I say that the visual images of objects which pass through that colour to the eye can either be impaired or improved, and the deterioration will happen to blue, black, and white more than to all the others; and the improvement will occur with yellow and green more than with all the others. Thus you will examine with the eye the mixtures of colours, which are infinite in number; and thus you can make a choice of colours for new combinations of mixed and composed colours. You may do the same with two glasses of different colours held before the eye and thus continue experimenting by yourself.

72

72

Make the rainbow in the last book on Painting but first write the book on colours produced by the mixture of the other colours, so that you may be able to prove by those painters’ colours the genesis of the rainbow colours.

73

73

Every object that has no colour in itself is tinged either entirely or in part by the colour set opposite to it. This may be shown for every object which serves as a mirror is tinged with the colour of the thing that is reflected in it. And if the object is white, the portion of it that is illumined by red will appear red; and so with every other colour whether it be light or dark.

Every opaque and colourless object partakes of the colour of what is opposite to it: as happens with a white wall.

74

74

Any white and opaque surface will be partially coloured by reflections from surrounding objects.

75

75

Since white is not a colour but is capable of becoming the recipient of every colour when a white object is seen in the open air all its shadows are blue . . . that portion of it which is exposed to the sun and atmosphere assumes the colour of the sun and the atmosphere, and that portion which does not see the sun remains in shadow and partakes only of the colour of the atmosphere. And if this white object did neither reflect the green fields all the way to the horizon nor yet face the brightness of the horizon itself it would undoubtedly appear simply of the same hue as the atmosphere.

76

76

Of colours of equal whiteness that will seem most dazzling which is on the darkest background, and black will seem most intense when it is against a background of greater whiteness. Red also will seem most vivid when set against a yellow background, and so will all the colours when set against those which present the sharpest contrasts.

77

77

How white bodies should be represented

If you are representing a white body let it be surrounded by ample space, because as white has no colour of its own it is tinged and altered in some degree by the colour of the objects surrounding it. If you see a woman dressed in white in the midst of a landscape that side which is towards the sun is bright in colour, so much so that in some portions it will dazzle the eyes like the sun itself; and the side which is towards the atmosphere,—luminous through being interwoven with the sun’s rays and penetrated by them—since the atmosphere itself is blue, that side of the woman’s figure will appear steeped in blue. If the surface of the ground about her be meadows and if she be standing between a field lighted up by the sun and the sun itself, you will see every portion of those folds which are towards the meadows tinged by the reflected rays with the colour of that meadow. Thus the white is transmuted into the colours of the luminous and of the non-luminous objects near it.

78

78

Every body that moves rapidly seems to tinge its parts with the impressions of its colour. This proposition is proved from experience; thus when the lightning moves among the dark clouds its whole course through the speed of its sinuous flight resembles a luminous snake. In like measure if you move a lighted brand its whole course will seem a circle of flame. This is because the organ of perception acts more rapidly than the judgement.

79

79

The art of painting shows by means of its science, wide landscapes with distant horizons on a flat surface.

80

80

The painter can suggest to you various distances by a change in colour produced by the atmosphere intervening between the object and the eye. He can depict mists through which the shapes of things can only be discerned with difficulty; rain with cloud-capped mountains and valleys showing through; clouds of dust whirling about combatants; streams of varying transparency, and fishes at play between the surface of the water and its bottom; and polished pebbles of many colours deposited on the clean sand of the river bed surrounded by green plants seen beneath the water’s surface. He will represent the stars at varying heights above us.

81

81

Of aerial perspective

There is another kind of perspective which I call aerial, because by the difference in the atmosphere one is able to distinguish the various distances of different buildings, which appear based on a single line; as for instance when we see several buildings beyond a wall, all of which are seen above the top of the wall look to be the same size; and if in painting you wish to represent one more remote than another you must make the atmosphere somewhat dense. You know that in an atmosphere of equal density the remotest things seen through it, such as mountains in consequence of the great quantity of atmosphere between your eye and them, will appear blue and almost of the same hue as the atmosphere itself when the sun is in the East. Therefore you should make the building which is nearest above the wall of its natural colour, but make the more distant ones less defined and bluer. . . .

82

82

The density of smoke from the horizon downwards is white and from the horizon upwards it is dark; and although this smoke is in itself of a uniform colour, this uniformity shows itself as different, on account of the difference of the space in which it is found.

83

83

Of trees and lights on them

The best method of practice in representing country scenes, or I should say landscapes with their trees, is to choose them when the sun in the sky is hidden; so that the fields receive a diffused light and not the direct light of the sun, which makes the shadows sharply defined, and very different from the lights.

84

84

Of the accidental colours of trees

The accidental colours of the leaves of trees are four, namely shadow, light, lustre, and transparency.

The accidental parts of the leaves of plants will at a great distance become a mixture, in which the colour of the most extensive part will predominate.

85

85

Landscapes are of a more beautiful azure when in fine weather the sun is at noon, than at any other time of the day, because the air is free from moisture; and viewing them under such conditions you see the trees of a beautiful green towards their extremities and the shadows dark towards the centre; and in the farther distance the atmosphere which is interposed between you and them looks more beautiful when there is something dark beyond, and so the azure is most beautiful.

Other books

The Sisterhood of the Dropped Stitches by Janet Tronstad

MWF Seeking BFF by Rachel Bertsche

Buried Fire by Jonathan Stroud

Endangered by Robin Mahle

A Royal's Love (Unit Matched #1) by Mary Smith

Tide of War by Hunter, Seth

En caída libre by Lois McMaster Bujold

Leaping Beauty: And Other Animal Fairy Tales by Gregory Maguire, Chris L. Demarest

The Wild Seed by Iris Gower

Family by Micol Ostow