Notebooks (28 page)

Authors: Leonardo da Vinci,Irma Anne Richter,Thereza Wells

Tags: #History, #Fiction, #General, #European, #Art, #Renaissance, #Leonardo;, #Leonardo, #da Vinci;, #1452-1519, #Individual artists, #Art Monographs, #Drawing By Individual Artists, #Notebooks; sketchbooks; etc, #Individual Artist, #History - Renaissance, #Renaissance art, #Individual Painters - Renaissance, #Drawing & drawings, #Drawing, #Techniques - Drawing, #Individual Artists - General, #Individual artists; art monographs, #Art & Art Instruction, #Techniques

The distance between the chin and the nose and that between the eyebrows and the beginning of the hair is equal to the height of the ear and is a third of the face.

96

96

The head

af

is ⅙ larger than

nf

.

97

af

is ⅙ larger than

nf

.

97

The foot from where it is attached to the leg to the tip of the great toe, is as long as the space between the upper part of the chin and the roots of the hair

ab

; and equal to five-sixths of the face.

98

ab

; and equal to five-sixths of the face.

98

For each man respectively the distance between

ab

is equal to

cd

.

99

ab

is equal to

cd

.

99

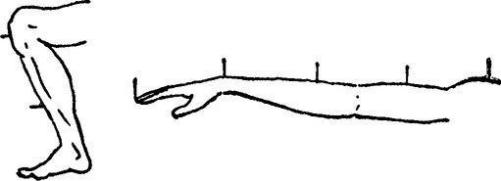

The length of the foot from the end of the toes to the heel goes twice into that from the heel to the knee, that is, where the leg-bone joins the thigh bone. The hand to the wrist goes four times into the distance from the tip of the longest finger to the shoulder-joint.

100

100

A man’s width across the hips is equal to the distance from the top of the hip to the bottom of the buttock, when he stands equally balanced on both feet; and there is the same distance from the top of the hip to the armpit. The waist, or narrower part above the hips, will be halfway between the armpits and the bottom of the buttock.

97

97

Every man at three years is half the full height he will grow to at last.

101

101

There is a great difference in the length between the joints in men and boys. In man the distance from the shoulder joint to the elbow, and from the elbow to the tip of the thumb, and from one shoulder to the other, is in each instance two heads, while in a boy it is only one head; because Nature forms for us the size which is the home of the intellect before forming what contains the vital elements.

Remember to be very careful in giving your figures limbs that they should appear to be in proportion to the size of the body and agree with the age. Thus a youth has limbs that are not very muscular nor strongly veined, and the surface is delicate and round and tender in colour. In man the limbs are sinewy and muscular; while in old men the surface is wrinkled, rugged and knotty, and the veins very prominent.

102

(102

b

) The Anatomy and Movement of the Body

The human body is a complex unity within the larger field of nature, a microcosm wherein the elements and powers of the universe were incorporated. In order to study its structure Leonardo dissected corpses and examined bones, joints, and muscles separately and in relation to one another, making drawings from many points of view and taking recourse to visual demonstration since an adequate description could not be given in words. According to him such visual demonstrations gave ‘complete and accurate conceptions of the various shapes such as neither ancient nor modern writers have ever been able to give without an infinitely tedious and confused prolixity of writing and of time’. Moreover, there are not only the various points of view, the infinity of aspects to be considered, there are also the continuous successions of phases in movements. The circular movements of shoulder, arm, and hand, for instance, is suggestive of a pictorial continuity such as we may see on a strip of film.

The study of structure included that of function, of the manner in which actions and gestures were performed, how the various muscles work together in bending and straightening the joints; how the weight of a body is supported and balanced. Leonardo looked upon anatomy with the eye of a mechanician. Each limb, each organ was believed to be designed and perfectly adapted to perform its special function. Thus the muscles of the tongue were made to produce innumerable sounds within the mouth enabling man to pronounce many languages. In his time divisions between the various branches of anatomy did not exist. He investigated problems of physiology and embryology, and the systems of nerves and arteries. He anticipated the principle of blood circulation and prepared the ground for further analyses on many subjects

.

.

You who say that it is better to watch an anatomical demonstration than to see these drawings, you would be right if it were possible to observe all the details shown in such drawings in a single figure, in which with all your cleverness you will not see or acquire knowledge of more than some few veins, while in order to obtain a true and complete knowledge of these, I have dissected more than ten human bodies, destroying all the various members and removing the minutest particles of the flesh which surrounded these veins, without causing any effusion of blood other than the imperceptible bleeding of the capillary veins. And as one single body did not suffice for so long a time, it was necessary to proceed by stages with so many bodies as would render my knowledge complete; this I repeated twice in order to discover the differences. And though you should have a love for such things you may perhaps be deterred by natural repugnance, and if this does not prevent you, you may perhaps be deterred by fear of passing the night hours in the company of these corpses, quartered and flayed and horrible to behold; and if this does not deter you, then perhaps you may lack the skill in drawing, essential for such representation; and if you had the skill in drawing, it may not be combined with a knowledge of perspective; and if it is so combined you may not understand the methods of geometrical demonstration and the method of estimating the forces and strength of muscles; or perhaps you may be wanting in patience so that you will not be diligent.

Concerning which things, whether or no they have all been found in me, the hundred and twenty books which I have composed will give verdict ‘yes’ or ‘no’. In these I have not been hindered either by avarice or negligence, but only by want of time. Farewell.

103

103

How it is necessary for the painter to know the

inner structure of man

inner structure of man

The painter who has a knowledge of the nature of the sinews, muscles, and tendons will know very well in the movement of a limb how many and which of the sinews are the cause of it, and which muscle by swelling is the cause of the contraction of that sinew; and which sinews expanded into most delicate cartilage surround and support the said muscle.

Thus he will in divers ways and universally indicate the various muscles by means of the different attitudes of his figures; and will not do like many who, in a variety of movements, still display the same things in the arms, the backs, the breasts, and legs. And these things are not to be regarded as minor faults.

104

104

In fifteen entire figures there shall be revealed to you the microcosm on the same plan as before me was adopted by Ptolemy in his cosmography; and I shall divide them into limbs as he divided the macrocosm into provinces; and I shall then define the functions of the parts in every direction, placing before your eyes the representation of the whole figure of man and his capacity of movements by means of his parts. And would that it might please our Creator that I were able to reveal the nature of man and his customs even as I describe his figure.

105

105

Remember, in order to make sure of the origin of each muscle to pull the tendon produced by this muscle in such a way as to see this muscle move, and its attachment to the ligaments of the bones. You will make nothing but confusion in demonstrating the muscles and their positions, origins and ends, unless you first make a demonstration of thin muscles after the manner of threads; and in this way you will be able to represent them one over the other as nature has placed them; and thus you can name them according to the limb they serve, for instance the mover of the tip of the big toe, and of its middle bone or of the first bone, etc. And when you have given this information you will draw by the side of it the true form and size and position of each muscle; but remember to make the threads which denote the muscles in the same positions as the central line of each muscle; and so these threads will demonstrate the shape of the leg and their distance in a plain and clear manner.

106

106

Of the hand from within

When you begin the hand from within first separate all the bones a little from each other so that you may be able quickly to recognize the true shape of each bone from the palm side of the hand and also the real number and position in each finger; and have some sawn through lengthwise, so as to show which is hollow and which is full. And having done this replace the bones together at their true contacts and represent the whole hand from within wide open. The next demonstration should be of the muscles around the wrist and the rest of the hand. The fifth shall represent the tendons which move the first joints of the fingers. The sixth the tendons which move the second joints of the fingers. The seventh those which move the third joints of these fingers. The eighth shall represent the nerves which give them the sense of touch. The ninth the veins and the arteries. The tenth shall show the whole hand complete with its skin and its measurements; and measurements should also be taken of the bones. And whatever you do for this side of the hand you should also do for the other three sides—that is for the palmar side, for the dorsal side, and for the sides of the extensor and flexor muscles. And thus in the chapter on the hand you will give forty demonstrations; and you should do the same with each limb. And in this way you will attain thorough knowledge. You should afterwards make a discourse concerning the hands of each of the animals, in order to show in what way they vary. In the bear for instance the ligaments of the tendons of the toes are attached above the ankle of the foot.

107

107

Other books

Coto's Captive by Laurann Dohner

The Stiff Upper Lip by Peter Israel

Submit to the Beast by April Andrews

The Ghost in the Electric Blue Suit by Graham Joyce

Tender Is the Night by Francis Scott Fitzgerald

The Danu by Kelly Lucille

Knight of Darkness by Kinley MacGregor

21/12 by Dustin Thomason

A Cold White Fear by R.J. Harlick

In Death's Shadow by Marcia Talley