One Day in December: Celia Sánchez and the Cuban Revolution (2 page)

Read One Day in December: Celia Sánchez and the Cuban Revolution Online

Authors: Nancy Stout

Knowing her as well as I now believe I do, I ask myself, Did we meet? I remember visiting Cuba for the first time in 1978. Celia would have been very ill by then; she died in 1980. I do recall a visit to the Federation of Cuban Women and if I’m not mistaken I met Vilma Espín, another remarkable revolutionary, and perhaps Haydée Santamaria, whom I surely had “met” in the story of the torture and murder of her brother Abel, one of those captured after the attack on the Moncada garrison in 1953. I remember Haydée especially for her reply to the guard who brought her one of her brother’s eyes:

If he would not talk, nor can I

.

I longed to learn the story of these women, so beloved of each other, so trusted and so true. Now I’ve learned part of it. This

story will no doubt be another medicine for our time: how to be completely trustworthy in times of battle; how to set out together, as women, to change the world, with men (happily) beside us or without them.

I wrote the poem below during the Arab Spring, when the people of Egypt rose up to begin the necessary change of their own corrupt society. It is dedicated to the Egyptian people. It seeks to speak to Cubans as well, and their country rich in martyrs.

Our Martyrs

When the people

have won a victory

whether small

or large

do you ever wonder

at that moment

where the martyrs

might be?

They who sacrificed

themselves

to bring to life

something unknown

though nonetheless more precious

than their blood.

I like to think of them

hovering over us

wherever we have gathered

to weep and to rejoice;

smiling and laughing,

actually slapping each other’s palms

in glee.

Their blood has dried

and become rose petals.

What you feel brushing your cheek

is not only your tears

but these.

Martyrs never regret

what they have done

having done it.

Amazing too

they never frown.

It is all so mysterious

the way they remain

above us

beside us

within us;

how they beam

a human sunrise

and are so proud.

CELIA, TOO, WAS A MARTYR

, though she lived nearly sixty years and died of natural causes, if cancer can be called natural. I believe, though, that the deeply harrowing and stressful work she did as a revolutionary, including protecting Fidel, whom she loved, and whom she understood to be Cuba’s rightful and destined leader, a leader always under attack, consumed her. Weighing on her also was the grief she had to repress when personal losses and tragedies intervened, in order to fulfill her duties to the Revolution and the country.

She always recalled their life up in the mountains. There, despite all kinds of hardship, they’d joined with families and clergy to witness marriages and baptisms, planted flowers, and conveyed battle news via radio broadcasts of music. In the steamiest days of August, they’d celebrated their leader’s birthday party and their confidence of imminent victory with a party and ice cream cake.

May the example of Celia Sánchez’s extraordinary life strengthen and encourage us. She kept records of virtually everything those around her did during the Revolution. In a way it is through this selfless wisdom, her caring about future rebels she saw coming to the place Cuba pioneered, that we most clearly see her.

Preface

BEFORE I KNEW

that she was a designated hero, I became interested in the projects she created.

Celia Sánchez’s name came up during my first trips to Cuba, in 1992 and 1993, when my assignment was to photograph architecture. And during my second series of trips, in 1995 and 1996, to research and document, through photography, Havana’s famous cigar industry, her name continued popping up. I was surprised to learn that Celia had been the power behind Cuba’s most profitable export cigar, the famous Cohiba, and to see a large portrait of her hanging in the factory that produces it. Her importance, the palpable essence of her power, impressed itself on me, but I had yet to learn about her association with Fidel and her role in the Revolution.

Those were especially bleak years, during the “special period,” and a friend, photographer Raul Corrales, confronted by food shortages, remarked sharply, “If Celia were alive, things wouldn’t be like this.” I had no reason to doubt him but little grasp of what he meant. “She was a big player in this chess game, the Cuban Revolution, which exists, whether you North Americans like it or not. It exists.”

LIKE MOST BIOGRAPHERS

, I researched my subject’s childhood, starting with her relationship to her mother, who died when Celia was six. Celia’s father was a country doctor, a bit glamorous, with

a taste for history and a library of fine books. I learned that Dr. Sánchez was a political activist who believed in social justice, a man who believed in a better future for all Cubans. I traveled to Manzanillo, and met the city’s historian, Delio Orozco. We traveled down the coast, visiting the historian of Campechuela, who told me how Celia had escaped from the military police by hiding in a thicket of thorns. We went to the place where she was arrested. There, I began to sense that her greatness might reside not so much in the buildings she’d produced as in her willingness to risk everything to rid Cuba of false leaders who relied on backing from both the United States and the Mob. I sensed that she was something of an avenging angel. Considering what I knew of her father, that seemed very much in Celia’s DNA.

I RETURNED TO CUBA

in 2000 having made a decision to write a book, though not yet this book. The plan then was a study, in text and photos, of her architectural and design projects in Havana: the Coppelia Ice Cream Park, the Convention Center, Lenin Park, and the many workshops she opened to furnish these. These three flagship projects could constitute a huge accomplishment for any woman. I’d supplement my own photographs with archival selections provided by the Ministry of Construction.

I started, comfortably enough, by contacting the architect she hired for the Coppelia project, Mario Girona, whose family and hers were related. I widened my contacts to include the rest of the Girona clan. They all had known Celia since childhood, and her father and theirs were best friends. Highly educated, one with a career in the diplomatic service, one a painter, all had spent time in the United States, and all spoke English. They were longtime leftists, communists from the old Partido Socialista Popular (PSP), and Celia had spent the better part of 1948 with them in Brooklyn. One, who’d mostly stayed in Cuba, had run money to Castro in Mexico. They were all stylish and comfortable and lived in an award-winning building, on the 18th, 20th, and 21st floors. The seven months of that year I lived in Havana saw many regularly scheduled brownouts, or blackouts, and I had to walk up all those flights. Once up there, you tend to stay.

I spent many hours with the family. At some point, the diplomat, Celia Girona, said that they’d feel more at ease if I met Flavia. So

she took me to see Celia’s sister. From the start, my sources were intimate, and having participated in one way or another in the Revolution, were politically comfortable. The Gironas’ only regret, seemingly, was not having fought in the Spanish Civil War.

QUITE A LOT HAD

been written about Celia over the years, as my bibliography reflects, but there was, curiously, no biography, no single-source reference on her life. Which was a great piece of luck. Detective work, hunting things down, following leads, finding people, asking them questions, and visiting the sites of events is what I love. The necessity of doing that made my project inexhaustibly engaging, and gave this book a personality I hope befits its subject.

Another bit of good luck was an introduction to Argelia Fernandez, translator-interpreter at a series of art, design, and architecture lectures at the Ludwig Foundation. Argelia and Celia had met, when Argelia and her ambassador husband had been posted in Paris and Beirut. Whatever qualms the Cubans may have had about me as biographer of their national hero were laid to rest when they saw that I was in Argelia’s hands. We developed a foolproof technique. Not just recording all interviews to transcribe later, I began to type “live” into my laptop as well. Each evening I’d go over the day’s interview. If something didn’t make sense, or had been a little shocking, Argelia and I would call our interviewee up and clarify: Is this what you said? Are you comfortable saying that? Argelia and I would discuss the meaning of a word, or we’d call in one of the old revolutionaries to verify what certain words, when used in the 1950s, in Oriente Province, meant. Or we’d contact members of the underground. We’d ask ourselves, Who else can tell us? And that could lead to another interview, another call. While we were nailing down the best translation and interpretation, we were, as it turned out, building confidence around town that the North Americana was trying to get it right.

Together, we talked to soldiers from the rebel army, then moved on to Celia’s friends and neighbors, hailing from the eastern end of the island, people who had known her before and during the war. Gradually, I met other members of the Sánchez family, nieces and nephews, and people who worked for Celia, in her household. These were normal people who, like it or not, had ended up with

a guerrilla fighter in the family. I found out what I could, and took an interest in everything they were willing to tell me. Ernestina Gonzalez, Celia’s cook going back to her years running her father’s house, drew a line at what she would discuss; she still worked for Fidel, and was reticent, as anyone would be, at discussing her employer. So we spoke about food, and I wrote down Celia’s winning recipes for stuffed turkey and mango upside-down cake.

SINCE NO ONE

had undertaken a biography, I found all these people who rightly considered themselves experts about the Celia they knew and loved. They had been waiting for someone to come hear their stories. My lead question was designed to put everyone on the same footing, and I hoped at ease. “Describe the first time you saw her,” I began. “Tell me, too, where it was and an approximate time or date. What she wore, and how you recall her voice.” I would add that I asked everyone I spoke with to do the same. People who were worried about saying the wrong thing soon relaxed. Later, I’d find out that people who’d spoken with me urged the more reluctant to go ahead. “She’s interested in details,” was the way they described me. Details became the sustaining element of my search and told me more about her and Fidel than anyone was ready to say.

It was only after hundreds of such conversations that I was granted access to documents held in the Archives of the Council of State, a collection of primary material from the Revolution, collected and organized by Celia herself. Each day, Argelia and I would go to the capital’s Linea Street, to a building once a bank, now a vault of history. We sat in an alcove where a banker once sat, behind a glass door, and read the letters written in the Sierra Maestra. Celia’s letters to her family and comrades, and theirs to her, informed and enriched what I’d learned in my many interviews and chats over coffee, juice and, occasionally, rum or beer. I went home, back to New York, to mull, digest, and organize Celia’s story. I’ve never tired of reliving it. My book does include those building projects that were my starting point, but only at the very end.

I traveled to Cuba on every vacation, wrote on weekends and mornings before going to work. I am glad that it took ten years to complete because so much, for the reader, has changed. At the beginning, I was assured the American reader’s ear—and eye, I suppose—could not possibly cope with Spanish names. But the world’s more global now, and of course our ears can hear names in other languages. And the grittiness, maybe we should say the prevarication or paradoxes of guerrilla warfare, that once horrified some of my friends, even made others indignant, have become understandable in light of the Arab Spring.

MY VERSION OF CELIA’S STORY

introduces many new characters to the history of the Cuban Revolution. Revolutionaries don’t act alone. Celia was supported and saved, more than once, by her family and friends. I have always been aware that if I didn’t include their parts of the story, too, maybe they wouldn’t be told. Many times in our conversations they prompted me to ask myself: What does it mean to have a friend, a daughter, or a sister who is a revolutionary?

NANCY STOUT

New York City

November 2012

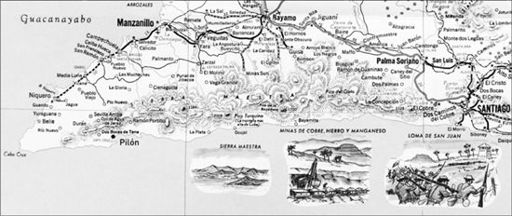

MAP OF CUBA (detail)