One Day in December: Celia Sánchez and the Cuban Revolution (3 page)

Read One Day in December: Celia Sánchez and the Cuban Revolution Online

Authors: Nancy Stout

The seat of the Cuban Revolution was located in the southwestern region of Orient Province, seen here in a detail of an Esso road map, Mapa de las carreteras de la Republica de Cuba, published in 1956. (

Courtesy of the Newberry Library

.)

Part I

PILÓN

1. D

ECEMBER

1955

A Tap on the Shoulder

IT IS A DAY IN PILÓN

much like any other, except that it’s late in the year, so it’s cooler and there is more traffic in town. Here on the island’s Caribbean coast, it is the start of the

zafra

. Sugarcane, bright green in the fields, arrives from the surrounding plantations on wagons that roll along the streets leading to the sugar mill. This is a factory town, but more reminiscent of the Wild West, with noise and bustle and farmers traveling the unpaved streets on horseback.

Celia, as always, wakes up early. Her bedroom sits to the back of the house, overlooking the patio and part of her garden. A door from her room leads directly onto a wide verandah. At its end, on a corner post, a radio occupies a shelf. She turns on the morning news, broadcast from Havana. The house is clapboard, L-shaped, single-storied, with verandahs on three sides, and stands elevated about three feet above humid ground. It is simple enough, but—and everyone agrees—it is the prettiest house in town. The furniture, mostly antique, includes Cuban pieces shaped from palm trees, woven from willow branches, or of pine clad in cowhide. The rest is imported: rattan from the Philippines, with slipcovered cushions, or her parents’ wedding furniture, made in Italy, carved and upholstered, and purchased from her Spanish grandfather’s department store in Manzanillo.

The Cabo Cruz sugar mill in Pilón, Oriente Province, Cuba. (

Courtesy of Oficina de Asuntos Históricos

)

Celia and her father live in one of the “yellow houses” inhabited mostly by mill management—called this not because they are painted that color but because they alone get a few hours’ electricity each day, and glow at night. Pilón is company-owned.

At the end of the year the southeast coast enjoys a breeze off the Caribbean and the air is fresh; it is the best time of year for growing flowers. Standing on the verandah, she can admire the gardens wrapping the house on three sides. As she walks along the side porch, she says a few affectionate words to the birds in cages hung at intervals along this outdoor living space: the glider, hanging swing, and rocking chairs are all empty at this early hour. What sets the house apart, besides Celia’s flair for decoration, are her father’s collections of books, artifacts, and nineteenth-century Chinese porcelain pieces, their colors predominantly vibrant shades of rouge, with black, green, and gold leaf accents.

She takes beauty seriously: her hands are carefully manicured; she always wears makeup, paints her lips bright red. She dresses well, copying clothing shown in

Harper’s Bazaar

and

Vogue

. She is extremely slender, but there is nothing flat about Celia. Errol Flynn later summed her up for the

L.A. Examiner

: “36-24-35.” The full-skirted dresses she favors, the look of the 1950s, show off her bust and narrow waist.

She pulls her thick black hair into a ponytail. Her look is pretty, but doesn’t stop there, surging over into another category suggesting, or revealing, maybe warning, that she is smart as well. Most telling is the way she shapes her eyebrows into thin, high arches with a line upward—like the accent marks over the final letters of José Martí.

In rope-soled

alpargatos

, with long multicolored ribbons tied securely around her ankles, she walks almost silently along the side porch to the front of the house where the porch gives onto the small front garden and the street. This section serves as the waiting room for patients. Coming in from surrounding plantations as well as the town, they await the doctor, who is still asleep. In this season, when the mill runs around the clock, patients begin to arrive at dawn or even wait through the night. Celia looks at the narrow strip of garden that separates the house from the street.

When I first visited Pilón in 1999, this little garden had dark red and bright green plants spelling CELIA on one side of the walk leading to the front door, FIDEL on the other.

CELIA’S LIFE FOLLOWS A CHARMING

, even genteel pattern: each day she goes into the kitchen to greet Ernestina, the cook, and they talk about various things: food and children, since Ernestina was expecting a child, and any bits of information Ernestina might have gleaned from neighbors on her walk to work. It is a conversation they have carried on for fifteen years.

The house and medical office of Dr. Manuel Sánchez. He and Celia moved to this house, in Pilón, in 1940. (

Courtesy of Oficina de Asuntos Históricos

)

Ernestina brews coffee, and Celia pours a cup and carries it to her father’s room, at the back of the house next to her own. In the bathroom with its smooth floor, walls, and ceiling finished in wood, she fills the porcelain tub, mixing the water carefully to temperature, and opens the window looking out on the inner garden. The window sill is so low that a person could leap straight from the tub onto the patio, paved in stone and shaded by a gigantic mango tree.

As the bath fills, Celia lays out towels, hangs a freshly laundered medical jacket on a hook on the wall, placing her father’s trousers, underwear, socks, and shoes nearby. Manuel Sánchez prefers lightweight Florsheims, American-made, but any attachment to the United States ends there, with those shoes.

In the kitchen, she’ll have cocoa and toast as she goes over the day’s menus. Celia has given Ernestina the menus for the week, loaded the pantry with provisions for the month—this is the tropics, even butter comes in a tin—and makes sure the vegetables and meat have been brought down from the family’s farm in the foothills of the Sierra Maestra. Even though Ernestina must know every recipe by heart, it is important that each dish be prepared the way Dr. Sánchez likes it. While he bathes, dresses, and has breakfast, Celia readies his three medical rooms. In the

consultorio

, she’ll file papers, straighten his desk, shelve books; in his surgery she’ll lay out instruments; and finally she will check the medical bag he’ll carry for afternoon house calls. She’ll keep an eye out for Cleever, the gardener, and, if the need arises, have him saddle horses and help load them into a launch, so she and her father can travel along the coast, disembark, and ride up into the mountains to make remote house calls. She also will make sure that their Ford has a full tank.

It is now 7:00 a.m. The office is about to open and Celia is ready to schedule. She will talk to all the patients waiting on the porch and learn why they have come. Not all visits to Dr. Sánchez are medical. Pilón, despite the greater area’s roughly 12,000 inhabitants, has no priest, and the nearest Catholic church with a priest in residence is in Niquero, about 25 miles away on roads marked on a 1945 map as seasonal with long impassable periods. Few people go to Niquero from Pilón unless they own a car—and few people do—and coastal ferries do not go there and return on the same day. So the doctor is consulted about family matters, abuse, disputes, confessions, ambitions; he sometimes acts as a marriage broker. Such consultations go hand in hand with diagnosis and treatment of malaria, water-borne diseases, tuberculosis, malnutrition, gunshot and knife wounds, and alcoholism, as well as the more natural adjuncts of a rural doctor, dentistry and delivering children. Everybody comes to Dr. Sánchez; he does not insist or even expect that all his patients pay.

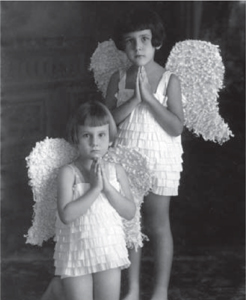

Celia (standing, left) was the middle child of eight children, preceded by Chela (Graciela), Silvia, the oldest, and Manuel Enrique. She was followed by Flávia (seated, front left), Orlando, in the middle, and Grisela. This studio photograph was taken in 1925 or 1926, before the birth of the baby Acacia and the death of Celia’s mother, Acacia Manduley. (

Courtesy of Oficina de Asuntos Históricos

)

Celia has been following this daily pattern for fifteen years, and soon will begin the sixteenth. Or so things appear. She isn’t stuck here in Pilón; she likes it and has a small side business selling accessories, for which she travels fairly often to Miami. She is her father’s assistant; people call her “the doctor’s daughter.”

He delivered her on May 9, 1920, at 1:00 p.m. at home, in Media Luna, a town farther up the coast. He and his wife, Acacia, took her to the civil registry on October 16, 1920, and registered

her as Celia Esther de los Desamparados Sánchez Manduley. Celia, after her grandfather Juan Sánchez y Barro’s first wife, Celia Ros; they chose her middle name from the liturgical calendar, Nuestra Señora de los Desamparados, our lady of abandoned ones. She was a middle child of eight children, preceded by Silvia, Chela, and Manuel Enrique, and followed by Flávia, Griselda, Orlando, and the baby Acacia, named after their mother. Celia’s mother died when she was six, and Celia had needed special attention following this separation because she had suffered mild anxiety neurosis, begun to cry frequently, developed a fever. Her father had kept her out of school, although she was nearly seven, to enter later with Flávia, who was a year and nine months younger. He taught her himself, and continued to do this even after she entered school, and hired special tutors for her.

Celia will work with her father until ten, or until he leaves the house for his small clinic in the sugar mill; then she is free to supervise the house or work on one of her many projects. She is an avid gardener, likes any activity that takes place outdoors, and she has a personality that is more cowgirl than housewife in this regard. Deep-sea fishing is her favorite sport, picnics her favorite pastime, and flowers—especially orchids—are her passion. Her main collaborator and sidekick, Cleever, is Jamaican, and lives with his wife at the edge of the garden. He keeps the shrubbery under control and implements her landscaping projects. The most recent are beds planted in patches of single colors to form designs. To make pocket money, she bakes and ices cupcakes, particularly during the harvest season, and Cleever takes them around town on a tray, knocking on back doors.