Operation Barbarossa and Germany's Defeat in the East (54 page)

Read Operation Barbarossa and Germany's Defeat in the East Online

Authors: David Stahel

Tags: #History, #Military, #General, #Europe, #Modern, #20th Century, #World War II

This certainly contributed very much to the amazingly quick establishment of the partisan units.

194

Even as the infantry of the

9th and

2nd Armies retraced the path of the motorised divisions there was no time to flush out the vast swamps and forests systematically looking for rogue enemy elements that were, in any

case, not yet fully recognised for the threat they posed. Yet to the German soldiers operating in the densely wooded regions the perils were soon well known. On 25 June

Ernst-Günter Merten wrote: ‘Yesterday afternoon we learned a new art of warfare: tree sniper fire. Unfortunately there were a few killed in the battalion…As the march continued everyone was a little nervous.’

195

Three days later Doctor

Hermann Türk noted in his diary: ‘Last night some more of our soldiers were shot by snipers.’

196

By early July Army Group Centre's rear area was becoming enormous, making control over the vast forests impossible. One soldier's letter, written at the beginning of July, suggested that the forests were more deadly than the battlefields:

Any snipers who fall into our hands are of course shot; their bodies lie everywhere. Sadly, though, many of our own comrades have been lost to their dirty methods. We're losing more men to the bandits than in the fighting itself.

Hardly any sleep to be had. We're all awake and alert almost every night. You have to be in case they attack suddenly. If the sentry drops his guard just once then it could be all over for us all. Travelling alone is out of the question.

197

With the passing of the combat formations, Army Group Centre's vast rear area was then to be governed by a handful of poorly equipped security divisions assisted by a collection of SS and police.

198

What these forces lacked in manpower and mobility to control the vast area, they sought to make up for by the unrestrained spread of terror throughout the occupied territories. Mass shootings and draconian rule were the order of the day – a formula which General

Lothar Rendulic bluntly illustrated with the maxim, ‘success comes only through terror’.

199

On 16 July Hitler also expressed his endorsement for such methods. ‘The Russians’, he declared, ‘have now ordered partisan warfare behind our front. This also has its advantages: it gives us the opportunity to…exterminate…all who oppose us.’

200

Conducting his war of annihilation under the veiled cover of a military operation against insurgents, Hitler soon enlisted the support of the OKW when

Keitel issued orders calling for the most ruthless measures to counter resistance in the rear areas.

201

The directive

appeared on 23 July and stipulated that resistance should be quelled ‘not by legal punishment of the guilty, but by striking such terror into the population that it loses all will to resist’.

202

Although the fierce resistance in the rear was initially sustained by the isolated mass of Red Army units trapped behind enemy lines, the lurid German terror sought to forestall any further popular resistance among the peasant

population.

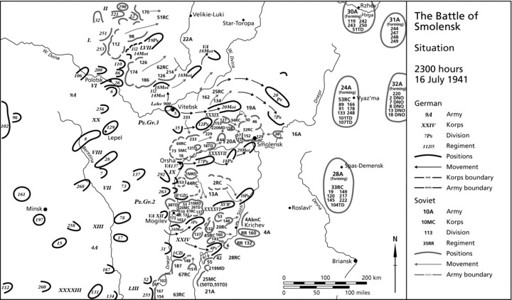

Map 7

Map 7

Dispositions of Army Group Centre 16 July 1941: David M. Glantz,

Atlas of the Battle of Smolensk 7 July– 10 September 1941

For all the burgeoning problems of logistics and security in the rear areas, the panzer and motorised divisions drove vigorously on, oblivious to the fading hope of eradicating organised Soviet resistance. On the surface the armoured forces still seemed capable of impressive action, with deep advances by all the armoured corps in the week following the penetration of the

Dvina and

Dnepr rivers (see

Map 7

), resulting most notably in the

29th Motorised Division fighting its way into

Smolensk on 16 July.

203

Yet the rigours of the advance meant the two panzer groups were fast running themselves into the ground. On 16 July

Lemelsen, the commander of the

XXXXVII Panzer Corps, advised higher command that the

18th Panzer Division could no longer be looked on as fully combat ready. His report stated that after 25 days of uninterrupted heavy fighting the division had suffered heavy losses in officers and men as well as weapons and trucks. ‘The heavy exhaustion of the troops’, the corps diary recorded, ‘had at times led to a completely apathetic attitude. Also the remaining serviceable material is so run-down, that further heavy fallout must be expected.’

204

Nor was the example of the 18th Panzer Division atypical. From an initial strength of 169 tanks, the 4th Panzer Division could field only 40 tanks by the evening of 17 July.

205

Likewise, the

10th Panzer Division reported on 16 July that the fallout rate among its tanks had ‘alarmingly increased’

206

with just 30 per cent of its original strength still serviceable.

207

The

7th Panzer Division began the war with close to 300 tanks, but by 21 July 120 of these were in repair and another 77 total losses, leaving only about one-third of its original

strength available for action.

208

Beyond motorised vehicles the army's other main source of transportation, the horse, was suffering too. In the sole cavalry division in the German army (1st Cavalry Division) a total of 2,292 horses had been lost in the period up to 12 July with just 1,027 captured horses to offset the deficit.

209

Although of less immediate importance to the prosecution of the war, personnel losses throughout the German army were also rising sharply, illustrating the intensity of the fighting. In just the first three and a half weeks (from 22 June to 16 July) German

casualties had reached 102,588 men,

210

a rate of loss sustainable given the available reserves, but only if the war remained short and hostilities were largely concluded by the end of the summer.

211

One of the central conditions for victory in Germany's war against the Soviet Union was the necessity of retaining mobility – both to outmanoeuvre and defeat the large Soviet armies and to ensure the occupation of enough industrial and economic centres to forestall continued large-scale resistance from the east. In short, the German army depended upon maintaining the swift pace of operations which typified its earlier successes. The fatal over-extension of its logistical system and the exhaustion of its panzer and motorised divisions before Smolensk may appear to be an unspectacular measure of defeat by the historical comparatives of

Waterloo or

Tannenberg, but a fundamental and ultimately ruinous defeat it remains. Germany did not fail in Operation Barbarossa by a crushing defeat in a major battle, nor can the performance of the Red Army take the credit; they failed by losing the ability to win the war. Yet it is for this same reason that the German defeat was not a knockout blow, but rather one which doomed Germany to fighting a war far different from the one the generals had planned and consequently were not prepared for. Caught in the vast Soviet hinterlands, the front promptly started to settle down into gritty positional warfare more reminiscent of World War I, while the war of manoeuvre became more and more limited to specific sectors of the front.

1

Karl Wilhelm Thilo, ‘A Perspective from the Army High Command (OKH)’, p. 301 (7 July 1941).

2

Italics in the original. Ibid., pp. 301–302 (8 July 1941).

3

‘KTB Nr.1 Panzergruppe 2 vom 22.6.1941 bis 21.7.41’ BA-MA RH 21–2/927, Fol. 133 (5 July 1941).

4

Von Manstein,

Lost Victories

, p. 193.

5

Hoepner's letter cited by Hürter,

Hitlers Heerführer

, pp. 287–288, footnote 37.

6

‘KTB Nr.1 Panzergruppe 2 vom 22.6.1941 bis 21.7.41’ BA-MA RH 21–2/927, Fol. 134 (5 July 1941).

7

Fedor von Bock, KTB ‘Osten I’, Fol. 15,

War Diary

, p. 239 (5 July 1941).

8

Guderian,

Panzer Leader

, p. 167.

9

Franz Halder, KTB III, p. 45 (5 July 1941).

10

Fedor von Bock, KTB ‘Osten I’, Fol. 17,

War Diary

, p. 240 (6 July 1941).

11

Alexander Werth,

Russia at War 1941–1945

(New York, 1964), p. 157.

12

Kershaw,

War Without Garlands

, p. 79.

13

Harrison E. Salisbury,

The Unknown War

(London, 1978), p. 26. For further examples see Paul Carell,

Hitler's War on Russia. The Story of the German Defeat in the East

(London, 1964), p. 44.

14

See examples provided in Chor'kov, ‘The Red Army’, pp. 424–425.

15

Franz Halder, KTB III, p. 47 (6 July 1941). The commander of Army Group Centre's Army Corps IX, General of Infantry Hermann Geyer, stated in his memoir that after 17 days of action, the so-called ‘Polish illness’ had claimed 500–600 men among his 3 divisions. More than likely the ‘Polish illness’ was a reflection of the poor sanitary conditions and inadequate diets of the men; Hermann Geyer,

Das IX. Armeekorps im Ostfeldzug 1941

(Neckargemünd, 1969), p. 77.

16

Kroener, ‘Die Winter 1941/42’, p. 884.

17

Frieser,

Blitzkrieg-Legende

, p. 400 (Karl-Heinz Frieser,

The Blitzkrieg Legend

, p. 318).

18

Franz Halder, KTB III, p. 47 (6 July 1941).

19

Müller, ‘Das Scheitern der wirtschaftlichen “Blitzkriegstrategie”’, p. 964.

20

Kempowski (ed.),

Das Echolot Barbarossa ’41

, p. 238 (5 July 1941).

21

Hürter,

Ein deutscher General an der Ostfront

, p. 65 (6 July 1941).

22

‘A.O.K.4 Ia Anlage zum K.T.B. Nr.8 Tagesmeldungen der Korps von 21.6.41 – 9.7.41’ BA-MA RH 20–4/162, Fol. 74 (6 July 1941).

23

Von Luck,

Panzer Commander

, p. 54. See also Department of the U.S. Army (ed.),

Military Improvisations During the Russian Campaign

(Washington, 1951), pp. 53–55.

24

Kesselring,

Memoirs

, p. 92.

25

Fedor von Bock, KTB ‘Osten I’, Fol. 18,

War Diary

, p. 242 (7 July 1941).

26

Hermann Rothe and H. Ohrloff, ‘7th Panzer Division Operations’ in David M. Glantz (ed.),

The Initial Period of War

, p. 380.

27

Landon and Leitner (eds.),

Diary of a German Soldier

, p. 76 (6 July 1941).

28

Blumentritt, ‘Moscow’, pp. 47–48.

29

Hürter,

Ein deutscher General an der Ostfront

, p. 63 (24 June 1941). See also Pabst,

Outermost Frontier

, pp. 13–14.

30

Knappe with Brusaw,

Soldat

, p. 213.

31

Claus Hansmann,

Vorüber – Nicht Vorbei. Russische Impressionen 1941 – 1943

(Frankfurt, 1989), p. 119.

32

‘KTB Nr.1 Panzergruppe 2 vom 22.6.1941 bis 21.7.41’ BA-MA RH 21–2/927, Fol. 149 (7 July 1941).

33

‘Kriegstagebuch der O.Qu.-Abt. Pz. A.O.K.2 von 21.6.41 bis 31.3.42’ BA-MA RH 21–2/819, Fol. 312 (7 July 1941).

34

‘Kriegstagebuch Nr.2 XXXXVII.Pz.Korps. Ia 25.5.1941 – 22.9.1941’ BA-MA RH 24–47/2 (5 July 1941).

35

On 6 July Schweppenburg's XXIV Panzer Corps reported the loss of 30 Panzer Mark IIIs and four Panzer Mark IVs as a result of using captured fuel supplies; ‘Kriegstagebuch der O.Qu.-Abt. Pz. A.O.K.2 von 21.6.41 bis 31.3.42’ BA-MA RH 21–2/819, Fol. 318 (6 July 1941).

36

Macksey,

Guderian

, pp. 138–139.

37

‘KTB Nr.1 Panzergruppe 2 vom 22.6.1941 bis 21.7.41’ BA-MA RH 21–2/927, Fol. 149 (7 July 1941).

38

Department of the U.S. Army (ed.),

Small Unit Actions

, pp. 91–92; see also: Horst Zobel, ‘3rd Panzer Division's Advance to Mogilev’ in David M. Glantz (ed.),

The Initial Period of War

, p. 393; Steiger,

Armour Tactics

, p. 79.