Oswald and the CIA: The Documented Truth About the Unknown Relationship Between the U.S. Government and the Alleged Killer of JFK (60 page)

Authors: John Newman

Setting aside the torture tactics, it was no wonder, given Alberu's apparent trustworthiness, that the CIA station chief Win Scott believed him and sent a message the following day saying the affair was "fact." Unless Alberu or his source was lying, it had to be a fact because Duran herself had "admitted" it. We will return to Duran's treatment later.

Because of the large redeaction preceding this part of the May 26 report, we do not know whether Duran was talking to a third person or to Alberu, and, if she was talking to Alberu, whether she knew he was a CIA agent. The FBI special agent sent to Mexico City in the wake of the assassination, Larry Keenan, reports that he heard from the FBI legal attache, Clark Anderson, that "Silvia Duran was possibly a source of information for Agency or the Bu- reau."106 The HSCA learned that the CIA had at least considered recruiting Duran. HSCA investigator Edwin Lopez recalls: "We saw an interesting file on Duran. It said that the CIA was considering using her affair with Carlos Lechuga [Cuban Ambassador to the U.N.] to recruit her." 107 Nevertheless, the Lopez Report was inconclusive on the subject of Duran's alleged intelligence ties.

Mexico City station chief Winston Scott wrote about the Lechuga- Duran affair in the manuscript that CIA counterintelligence chief Angleton scarfed up after Scott's death.'O" Strangely, the CIA has redacted Lechuga's name from the spot in the Lopez Report that discusses this, even though the Agency released Proenza's statement that the Cubans had "employed" Duran's sexual services to entrap Lechuga (discussed in Chapter Fourteen).109 It is unclear what the CIA is hiding under this redaction. When this hidden text was shown to David Phillips, he professed surprise and added, "No one let me in on this operation." 10

Besides Charles Thomas and Luis Alberu, Phillips provides another intriguing episode in the Oswald-Duran sex story. During his interview with the HSCA, Phillips at first claimed ignorance with respect to any CIA interest in Duran. After being surprised by the "operation," Phillips still said he doubted that the station would have "pitched" [tried to recruit] Duran "because the Station could not identify her weaknesses." The Lopez Report then indicates this occurred:

The Committee staff members then told Mr. Phillips about the reporting on file concerning Ms. Duran from one of the Station's [I entire line redacted]. At one point [name redacted] had reported to his case officer that all that would have to be done to recruit Ms. Duran was to get a blonde, blue-eyed American in bed with her. With this, Mr. Phillips said that it did indeed sound as if the Station had targeted Ms. Duran for recruitment, that the Station's interest had been substantial, and that the weaknesses and means had been identified."'

This sequence of denial, professed ignorance, surprise, and then agreement appears contrived. Phillips had served as chief of Cuban operations at the CIA Mexico City station right after Oswald's visit. It strains credibility to think that Phillips would have been unaware of any operation involving Duran or the Cuban Consulate.

The CIA station's chief of Cuban operations, the Agency's ace spy inside the Cuban Embassy, and the embassy's political officer is nevertheless a powerful combination for any story, let alone this one. Alberu's report also included other contextual-and apparently supporting-details. He reported that Duran declared she had cut off all contact with the Cubans since her arrest and interrogation, and that she suspected her phone was tapped by the Mexican police or the CIA. Then something odd occurred at the end of the May 26 report:

[Redacted] counseled [Alberu] against any further contact with the Durans on the grounds that it might put him under some sort of suspicion either in the eyes of the Mexican police or the Cubans. He pointed out that little or nothing was to be gained from such a contact.' 12

If Alberu had not understood that the truth about Oswald's affair with Duran was not something the CIA wished to hear more about, this directive from Alberu's case officer made that point. But why not look into this matter further?

The HSCA had been given just enough material to suggest that the affair was real. Again, the fact that Duran was working for the Cuban Consulate, when combined with the intelligence reporting that alleged that her sexual services had been used for the Cuban government on a previous occasion, was dynamite. It made it look as if the Cuban government might have been involved in the assassination. In the next chapter we will add to this the story that Oswald threatened to kill Kennedy when he visited the consulate. For now we need to finish placing the pieces we have discussed in this chapter.

In view of the above, the HSCA naturally wanted to look closely at Duran's personality file in the Mexico City station. "This Committee has asked the CIA to make Mrs. Duran's Mexican "P" (personality) file available for review," the Lopez Report explained. "The CIA informed the Committee," the report stated, "that there was no "P" file available on Mrs. Duran.""' This might have been a lie, if the newly released CIA documents are genuine. On one of the documents associated with Charles Thomas is a "P" file number that appears to belong to Silvia Duran.""

Finally, we return to Charles Thomas, who upon retiring from the State Department in 1969, again stirred up the Oswald-Duran sex story, this time with Secretary of State William Rogers. "I believe the story merits your attention," Thomas wrote to the secretary. "Since I was the Embassy officer in Mexico who acquired this intelligence information," Thomas wrote, "I feel a responsibility for seeing it through to its final evaluation.""' Were Thomas's motives pure? Perhaps. But from the newly released CIA files a new twist has emerged in his story. This particular career Foreign Service officer had been working for the CIA all along-for Branch 4 of the Covert Action Staff.' 16

The anomalies in the story about Oswald's activities in Mexico City that proliferated in CIA channels do seem to fall into a pattern suggesting an extraordinary possibility: The story was invented after the Warren Commission investigation to falsely implicate the Cuban government in the Kennedy assassination. In this regard, the ease with which Lopez convinced Phillips about the sex story now stands out like a beacon. But who was the spider and who was the fly.

And what about Charles Thomas? His previous assignment had been to Haiti, from January 8, 1961 until the "summer" of 1963. DeMohrenschildt arrived there on June 2, 1963, and it seems likely that both men were there at the same time. In another interesting coincidence, in the fall of 1969, Thomas became involved in deMohrenschildt's business deals with the Haitian government. This involvement continued after Thomas's retirement. "I would ... be interested in knowing," Thomas's lawyer wrote in 1970, "whether you have found a solution to the problem of helping Mr. deMohrenschildt." 117

In Mexico City in 1965, however, Charles Thomas was a CIA covert action operative, and a key player in the development of the Oswald-Duran sex story. That story gained credibility in CIA channels in a way that leaves open an unsavory possibility: the story may have been invented after the Warren Commission investigation to falsely implicate the Cuban government in the Kennedy assassination.

CHAPTER NINETEEN

The Smoking File

Within the labyrinth of Oswald's intelligence files at CIA headquarters is a set of papers which, together, demonstrate that the Agency had a keen operational interest in Oswald's activities during the eight weeks before the murder of President Kennedy. The story contained in these documents comes from sources in two different locations: FBI sources in New Orleans and CIA sources in Mexico City. These documents include cable traffic between the CIA and its Mexico City station concerning Oswald's visit there, Agency copies of FBI reports on Oswald received in the fall of 1963, and the CIA's reports to the FBI, State, and Navy.

The extent of interest in Oswald during those fateful final two months was inextricably intertwined with details about Oswald known to the Agency and its Mexico City station at the time. The CIA has doggedly withheld some of these details from public view. A few documents released years ago were suggestive, such as the Kalaris memo discussed in Chapter Eleven. It had mentioned-possibly in violation of this security blanket-October 1963 cables about Oswald's activities in the Cuban Consulate. The Agency has long claimed, falsely, that it did not know of his visits there until after the assassination. As we will see, this story was concocted as a cover to protect the Agency's sources in Mexico City. In addition, newly released documents prove that the CIA was spinning a false yarn about Oswald before the assassination. The Oswald deception cooked up at CIA headquarters began on October, 10, 1963, the day after the CIA station reported his presence in Mexico City.

The interlocking cables, cover sheets, and reports on Oswald that collectively formed his CIA file-from late September to late No vember 1963-revealed a remarkable change in Oswald's internal record. As Oswald made his way to Mexico, a new data stream collided with his 201 file. That information was the FBI's reporting on Oswald's FPCC activities, a story we dealt with in detail in Chapters Sixteen and Seventeen. It "collided" in the sense that it did not merge with his 201. Instead, the FPCC material effectively knocked aside the 201 file in favor of a new, operational file.

A week after Oswald's departure from Mexico, another data stream on Oswald surfaced in the CIA, this one from the Agency's own surveillance net in Mexico City. Strangely devoid of anything about Cuba or the FPCC, this information was merged with Oswald's 201 file. Thus, the two streams were kept in separate compartments-the 201 and 100-300-11 files-and not permitted to touch until the assassination of the president. It is the thesis of this chapter that the connection between these two compartments was known before the assassination, a connection closely held on a "need-to-know" basis. Together they formed the real Oswald file, a set of records that might appropriately be referred to as a "smoking file." On November 22 this file was smoldering in the safes at headquarters: The accused assassin of the president had been involved in very sensitive CIA operations.

The Hidden Compartments in Oswald's CIA Files

Prior to Oswald's trip to Mexico City, information on his activities reached the CIA via FBI, State, and Navy reports.' Again, the "routing and record" sheets attached to these reports tell us who read them and when they read them. They show how the collision between Oswald's 201 and his FPCC story altered the destination of incoming FBI reports to a new file with the number 100-300-11.

What did this new number signify? On August 24, 1978, the CIA responded to an HSCA inquiry about Oswald's various CIA file numbers. That response contained this paragraph:

The file 100-300-011 is entitled "Fair Play for Cuba Committee." It consists of 987 documents dated from 1958 through 1973. All but approximately 20 are third agency (FBI, State, etc.) documents.'

(Note: FPCC portion of the above quote classified until 1995).

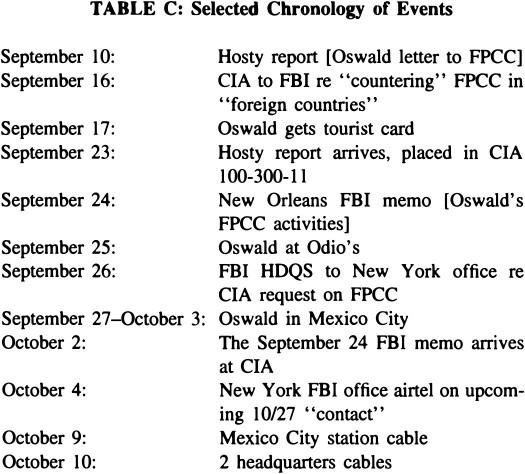

CIA documents lists show that Hosty's September 10, 1963, report-the first piece of paper associating Oswald with the FPCC- was the catalyst for the diversion of the FBI data stream into 100- 300-11.3 The routing and record sheet attached to this report shows this redirection occurred on the afternoon of September 23. The documents lists show that Hosty's report was also filed in Oswald's CI/SIG soft file and in his security file, OS 351-164, a point to which we will return momentarily.

By traveling to Mexico City and contacting both the Soviet and Cuban consulates there, Oswald inserted himself into the middle of an elaborate complex of espionage and counterespionage. This resulted in message traffic from the Mexico City station that was entered into his 201 file. The bifurcation of the New Orleans and Mexico City data streams into separate locations is fascinating. This is all the more so because the mechanism for this separation, the 100-300-11 file, was set into motion in the hours before Oswald departed for Mexico City, when Hosty's report from Dallas arrived. That seminal report contained the opening move of Oswald's FPCC game, but the routing and record sheet is strangely devoid of any indication that a Cuban affairs (SAS) office read it." The document was read primarily by counterintelligence elements. After this report, three major FBI reports on Oswald, all of them from the New Orleans office, were placed in the 100-300-11 file. After the Kennedy assassination, all four FBI reports reverted into Oswald's 201 file.

What was the purpose behind the separation of the New Orleans and Mexico City data streams? It might have been sloppy CIA accounting. But it might have been more: Could Oswald's trip have been part of a CIA effort at countering the FPCC in foreign countries and "planting deceptive information which might embarrass" the FPCC?5 The still-classified September 16 CIA memo to the FBI discussing such efforts is the beginning of a suggestive sequence of events.6 Was it just a coincidence that the next day Oswald and a CIA informant stood next to each other in a line to get Mexican tourist cards? Was the compartmentation of the FBI reporting on Oswald's FPCC activities-which began six days later-related? Were these all random events or were they connected: