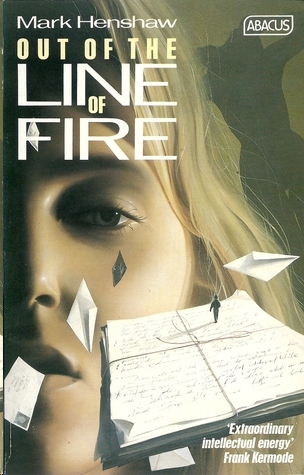

Out of the Line of Fire

MARK HENSHAW was born in Canberra in 1951. He studied at the Australian National University and the University of Heidelberg in Germany.

His first published work,

Out of the Line of Fire

(1988), was one of the best selling literary novels of the decade in Australia and has been widely translated. It won the FAW Barbara Ramsden Award and the NBC New Writers Award, and was shortlisted for the Miles Franklin Literary Award and the

Age

Book of the Year Award.

In 1989 Henshaw was awarded a Commonwealth Literary Fellowship, and in 1990 he held the Nancy Keesing Studio residency at the Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris. He received the ACT Literary Award in 1994.

Under the pseudonym J. M. Calder, he has written two crime novels in collaboration with the Canberra writer John Clanchy:

If God Sleeps

(1996) and

And Hope to Die

(2007). Both were published in Germany and in France, where they were subsequently republished in Gallimard’s Classic Crime Novels series.

From 1986 Henshaw was a Curator of International Art at the National Gallery of Australia. In 2011 he returned to writing full time. His second novel,

The Snow Kimono

, was published by Text in late 2014. It will be published in the United Kingdom and France in 2015.

At various times Mark Henshaw has lived in France, Germany, Yugoslavia and the United States. He lives in Canberra and, when not writing, enjoys spending time on the Australian coast. He is married with two children.

STEPHEN ROMEI is a journalist, writer and critic. He is literary editor of the

Australian

newspaper and a former editor of the

Australian Literary Review

.

ALSO BY MARK HENSHAW

The Snow Kimono

With John Clanchy, as J. M. Calder

If God Sleeps

And Hope to Die

textclassics.com.au

textpublishing.com.au

The Text Publishing Company

Swann House

22 William Street

Melbourne Victoria 3000

Australia

Copyright © Mark Henshaw 1988

Introduction copyright © Stephen Romei 2014

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright above, no part of this publication shall be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

First published by Penguin 1988

This edition published by The Text Publishing Company 2014

Cover design by WH Chong

Page design by Text

Typeset by Midland Typesetters

Primary print ISBN: 9781922182555

Ebook ISBN: 9781925095463

Author: Henshaw, Mark, 1951-

Title: Out of the line of fire / by Mark Henshaw ; introduced by Stephen Romei.

Series: Text classics.

Dewey Number: A823.3

CONTENTS

Where Truth Lies

by Stephen Romei

Where Truth Lies

by Stephen Romei

MARK Henshaw’s enigmatic and intriguing novel

Out of the Line of Fire

, published in 1988, the nation’s bicentenary year, sparked a debate about Australian writers’ place in the world and the relationship of their work to exciting developments elsewhere. It was the same year that

Love in the Time of Choler

a was first published in English—Gabriel García Márquez being the novelist who Peter Carey says ‘threw open the door I had been so feebly scratching on’. Eminent Australian critics such as Don Anderson, Peter Pierce and Helen Daniel lauded this debut novel by a thirty-seven-year-old Canberra-born writer, both for its European sensibility and postmodern inclinations, making comparisons with authors such as Italo Calvino and Peter Handke (who are among those with cameos in the book). Others complained on the same grounds, with David Parker arguing that Henshaw’s sophisticated European setting and high-literary references, and readers’ appreciation of same, were merely a new manifestation of the old cultural cringe. (‘Burying the hick, speaking as the chic’ was a clever line.)

It’s not every novel that arouses such passions, not by a long shot.

Out of the Line of Fire

was shortlisted for the 1989 Miles Franklin Literary Award, though the laurel went to Carey for

Oscar and Lucinda

which, due to a shift in the Miles Franklin timetable, had already won the Booker. As an aside, it is to the credit of the judges that Henshaw’s novel, with its ambiguous connection to ‘Australian life’, was recognised, when in more recent times important works such as David Malouf’s

Ransom

and J. M. Coetzee’s

The Childhood of Jesus

have not been.

So what is

Out of the Line of Fire

about? Well, that’s a good question, one I suspect the author—most authors?—would prefer go unanswered. As there will be readers who are encountering the book for the first time, I will not give away too much of the plot—the novel is on one level a thriller, after all—and I most certainly will not reveal the radical ending, which readers tend to take as a slap in the face or a pat on the back, depending on what they believe a novel is supposed to do. But here is a synopsis, just so you know the book you hold in your hands is not about, say, a child befriending a pelican.

Out of the Line of Fire

is in three parts. In the opening section we meet a narrator, an unnamed Australian writer living in an apartment building in ‘romantic Heidelberg, Germany’s oldest university town’ at the start of the 1980s. He is befriended by Wolfi Schönborn, a brilliant Austrian student of philosophy. He becomes fascinated with Wolfi’s early life and fractured family. But this narrator is an outsider. We are reminded, via Kafka, that Australia was a penal colony. In Europe in the early 1980s, Australia signifies only distance, physical and cultural. ‘For a long time now,’ the narrator tells us, ‘I have had the impression that I observe life but don’t participate in it, that somehow life flows straight through me as if I were transparent.’

He makes a study trip to Rome and when he returns Wolfi is gone, to Berlin it is said. ‘It was as though he had never existed, and a couple of weeks later I returned to Australia without having seen or heard from him again.’ So, in the space of twenty-odd pages, we have cause to wonder about the very existence of our narrator and our protagonist.

At the end of part one, the narrator, back home in Australia in September 1982, receives in the post a ‘carefully wrapped cardboard carton’ which contains Wolfi’s writings, along with photographs, news clippings, letters, postcards and other miscellany. This is accompanied by an ‘infuriatingly brief’ note: ‘Perhaps

you

can make something of this.’

In part two of the novel, the narrator retreats behind a curtain, becoming the unseen editor parsing Wolfi’s papers to try to reconstruct his life: his intense relationship with his mother and sister, Elena; his deflowering by Andrea, a prostitute hired by his grandmother; his involvement, in Berlin, with the members of an experimental theatre group, most importantly the charismatic, criminal Karl. This long section contains the explicit sex and violence that confronted some readers when the novel was published.

The scene with the prostitute is pivotal. It also has one of the funniest lines I’ve read in fiction: ‘For the first time in my life, with Andrea bent tenderly over me, I became conscious of the

real

implications of the Hegelian dialectic…’ The experience is transformative in other ways, too. ‘I am a man,’ Wolfi announces to his family. Elena is impressed. She kisses him on the mouth, and ‘After that night things were never to be the same.’

In the short and powerful final section of the novel the narrator, on an academic trip to Berlin in June 1986, stumbles across information that leads him to find out what happened to Wolfi, the role Karl played in his fate, and the true nature of Wolfi’s relationships with his father, mother and sister. Or maybe not. As I have said, the reader has a surprise in store that puts phrases such as ‘what happened to’ and ‘true nature’ on shifting ground.

Henshaw makes no secret of his metafictional intention to interrogate the lines between fiction and reality, between writer, character and reader. Four pages in, the narrator muses:

So there appear to be at least two problems confronting the writer writing about real events. Firstly, the words he or she uses seem to add some sort of fictionalizing distortion to the events they purport to describe and, secondly, even when a writer thinks they have got it right there still appears to be infinite room for ambiguity and imprecision. You begin to wonder where truth actually lies.

‘Where truth lies’ would be a good alternative title for this novel. The actual title words appear once, when we read of the late-teen Wolfi being awoken one morning by a shaft of sunlight reaching through the shutters of a hotel bedroom he shares with his sister, who is sixteen. He moves his head ‘out of the line of fire’ and looks at his sleeping sibling. Her left breast has come free of her nightdress. This ‘sudden confrontation with Elena’s emerging beauty’ is overwhelming, agonising, a rending of the soul. ‘It was as though, unable to raise my hands quickly enough, I had suddenly been blinded by the glare from some accidentally perceived truth.’ Another sort of fire, it suggests the start of something dangerous.

Later, when Wolfi is being persuaded by Karl to mug an older, ‘dignified-looking’ man cruising for gay sex in a public toilet—a sequence that in its irrational yet unavoidable violence evokes the climactic scene of Camus’s

The Outsider

—he thinks (or so we are told): ‘I felt like a character in a novel written by himself who runs into a character in a novel written by himself.’ Indeed, Henshaw starts this winking at the reader before the novel even begins. It makes me chuckle, still, to read in my 1988 Penguin edition the standard disclaimer that ‘All characters are fictional. Any similarity between persons living or dead is purely coincidental’ and then, on the facing page, the dedication ‘For Wolfi’. I know some people don’t like being winked at, but in this case I think it is a compliment: the author is inviting us to take part in his creation.

When I read

Out of the Line of Fire

a quarter of a century ago I was about the same age as its pointedly unreliable narrator. I was thrilled to find an Australian novelist writing about European authors I was only just getting to know: Calvino and Handke, Kafka and Camus, Robert Musil. Rereading the book I better appreciate the nuances of Henshaw’s conversation with these writers.