Overlord (Pan Military Classics) (23 page)

Read Overlord (Pan Military Classics) Online

Authors: Max Hastings

In the first six days ashore, the Canadians lost 196 officers and 2,635 other ranks, 72 and 945 of these, respectively, being killed. After the 9th, the Germans broke off their attacks for some days. The Canadians were able to consolidate their positions and plug the gaps in their line; they could draw satisfaction from beating off 12th SS Panzer’s attacks. Yet if the Germans were dismayed by their failure to break through to the sea, the Canadians had also proved unable to maintain the momentum of D-Day. Meyer’s panzers had successfully thrown them off balance: they now concentrated chiefly upon holding the ground that they possessed, and were most cautious about launching any attacks without secure flanks and powerful gun and tank support. They found themselves unable to advance beyond Authie.

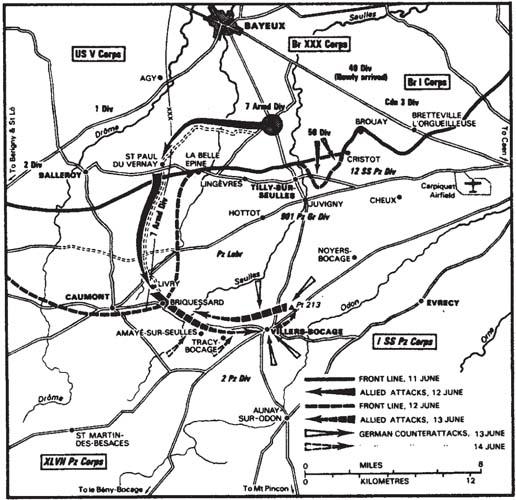

On 7 June the British 50th Division, on the right, occupied Bayeux, which the Germans had evacuated on D-Day, and pushed forward more than three miles towards Tilly-sur-Seulles, Sully, and Longues. Yet when Montgomery himself came ashore to establish his tactical headquarters in the grounds of the château at Creully on 8 June, the leading assault units, which had landed on D-Day and been continuously in contact with the enemy ever since, were visibly weary. The prospect of breaking through the line held by 12th SS Panzer and 21st Panzer in front of Caen was very small. ‘The Germans are doing everything they can to hold onto Caen,’ Montgomery wrote to the Military Secretary at the War Office that day. ‘I have decided not to have a lot of casualties by butting against the place. So I have ordered Second Army to keep up a good pressure at and to make its main effort towards Villers-Bocage and Evrecy, and thence south-east towards Falaise.’

6

Despite the worsening weather, which had restricted air support and delayed the progress of unloading, it is impossible now to forget Montgomery’s parting address to his commanders before they sailed for Normandy:

Great energy and ‘drive’ will be required from all senior officers and commanders. I consider that once the beaches are in our possession, success will depend largely on our ability to be able to concentrate our armour and push fairly strong armoured columns rapidly inland to secure important ground or communications centres. Such columns will form

firm bases in enemy territory

[emphasis in original] from which to develop offensive action in all directions.

7

For all Montgomery’s declarations of willingness to regard the independent armoured brigades, with their formidable tank strength, as ‘expendable’ in pursuit of these objectives, they had scarcely been attempted, far less attained. Second Army’s efforts had been entirely absorbed by the struggle to create and hold a narrow perimeter; and this despite the overwhelming success of the FORTITUDE deception plan, and a rate of buildup by Rommel’s forces as slow as the most optimistic Allied planner could have hoped for. In these first days, as much as at any phase of the campaign, the Allies felt their lack of an armoured infantry carrier capable of moving men rapidly on the battlefield alongside the tanks. From first to last, infantry in Normandy marched rather than rode, sometimes 10 or 15 miles in a day. Too many tired soldiers were asked to march far as well as fight hard. It took days for some units to re-adjust themselves after the huge psychological effort and surge of relief attached to getting ashore. In the training of paratroops, great emphasis is laid upon the fact that the act of jumping is a beginning, not an end in itself, and that their task commences only when they have discarded their harness on the ground. Yet throughout the months of preparation in England, the thoughts of the armies were concentrated overwhelmingly upon the narrow strip of fire-swept sand that they had been obliged to cross and hold on D-Day. Brigadier Williams of 21st Army Group said: ‘There was a slight feeling of a lack of cutting edge about operations at the very beginning after the landing.’

8

A less tactful critic might have expressed the issue more forcefully,

and compared the ruthlessness with which 12th SS Panzer and Panzer Lehr threw themselves into the battle with the sluggishness of Allied movements in those first, vital days before the mass of the German army reached the battlefield. The loss of momentum in the days after 6 June provided the Germans with a critical opportunity to organize a coherent defence and to bring forward reinforcements to contain the beachhead. The huge tactical advantage of surprise had already been lost.

On the evening of 9 June, Bayerlein’s superb Panzer Lehr Division moved into the line on the left of 12th SS Panzer after a 90-mile drive to the front from Chartres, during which they were fiercely harassed and strafed by the Allied air force. The formation had lost 130 trucks, five tanks and 84 self-propelled guns and other armoured vehicles. But the delay and dismay it had suffered were more serious than the material damage to its fighting power, since its total complement of tanks and vehicles was around 3,000. The three panzer divisions – 21st, 12th SS and Panzer Lehr – now formed the principal German shield around Caen, supported by the remains of the various static divisions that had been manning the sector on D-Day. 21st Panzer’s poor performance and reluctance to press home attacks were a source of constant complaint by Meyer’s Hitler Jugend, who claimed that in several battles already they had been let down by Feuchtinger’s units. But Panzer Lehr, for all their misfortunes on the road, were fighting superbly to hold the ruins of Tilly, the little town in a valley south-east of Caen which was to be the scene of some of the most bitter fighting of the campaign. Their panzergrenadier half-tracks had been sent to the rear, for they did not expect to move far or fast in any direction. Instead, the infantry were deployed in ditches and ruined houses alongside tanks employed as mobile strongpoints, meticulously camouflaged and emplaced to present only a foot or two of turret to attacking Allied armour. The tracks that they made approaching their positions were painstakingly swept away or concealed before daylight brought the spotter planes. Caked in dust, unwashed and often unfed, in the appalling heat and stink of their

steel coffins, the tank crews fought through days and nights of attack and counter-attack, artillery and naval bombardment, mortaring and Allied tank fire. The panzergrenadiers found the Tilly battle especially painful because it was difficult to dig deep in the stony ground, and at times of heavy bombardment their officers had difficulty holding even Bayerlein’s men from headlong flight.

For the British 50th Division also, the lyrical name of Tilly-sur-Seulles became a synonym for fear and endless death. The little fields of cowslips and buttercups, innocent squares of rural peace, became loathsome for the mortal dangers that each ditch and hedgerow concealed. The guidebook prettiness of the woods and valleys, so like those of Dorset and Devon, mocked their straining nerves and ears, cocked for the first round of mortar fire or the sniper’s bullet. For the tank crews, there was the certain knowledge that a hit from a German Tiger, Panther or 88 mm gun would be fatal. The same was not true the other way around.

The tension before a set-piece attack was appalling [wrote a young Churchill Crocodile troop commander, Andrew Wilson]. When Crocodiles were used, they were generally in the lead . . . You wondered if you’d done the reconnaissance properly; if you’d again recognise those small landmarks, the isolated bush, the dip in the ground, which showed you where to cross the start-line. You wondered if in the smoke and murk of the half-light battle, with your forehead pressed to the periscope pad, you’d ever pick out the target. And all the while you saw in your imagination the muzzle of an eighty-eight behind each leaf.

Then the bombardment grew louder, and the order came: ‘Advance’ . . . There was the run with the blurred shape of the copse at the end. Spandaus were firing, but you couldn’t see them. A Sherman officer was telling his troop to close up. The distance shortened. The Crocodiles began to speed up, firing their Besas. The objective took on detail. Individual trees stood out, and beneath them a mass of undergrowth. Something slammed through the air.

9

He knew at once that it was an anti-tank gun. But there was nothing he could do about it. The troop ran in, pouring in the flame. Once he thought he heard a scream, but it might have been the creak of the tracks on the track guides. Suddenly it was all over. The infantry came up and ran in through the smoke. The flame-gunners put on their safety-switches, and from inside the copse came the rasp of machine-guns. A little later, when he drove back to refuel, he saw that the field was littered with dead infantry and that one of the Shermans had been hit through the turret.

Villers-Bocage

It was at this stage that Montgomery determined to commit his two veteran divisions of the old Eighth Army, 51st Highland and 7th Armoured. ‘You don’t send your best batsman in first,’ he had said crisply before D-Day when one of a group of 7th Armoured officers asked – in a spirit that might not have been shared by some of his colleagues – why the formation was not to take part in the initial landings.

1

Now, he proposed to use his ‘best batsmen’ in two major flank attacks around Caen: 51st Highland would pass through the 6th Airborne bridgehead east of the Orne; 7th Armoured would hook to the south-west. The landings of the 7th Armoured and 51st Highland had been delayed by the weather, which was also causing serious artillery ammunition shortages. Beach organization and traffic control remained a chronic problem – on Gold alone, the engineers had been compelled to deal with 2,500 obstacles, many of them mined, comprising a total of 900 tons of steel and concrete. Nuisance night raids by up to 50 Luftwaffe aircraft constituted no major threat to the beachhead, but compounded delays and difficulties. Sword beach continued to be plagued by incoming shellfire.

Throughout these days, the German army mounted no major counter-attack. A desperate plan contrived by General Geyr von Schweppenburg of Panzer Group West was aborted by Rommel on 10 June – insufficient forces were concentrated. The following day, Geyr’s headquarters were pinpointed by Allied Ultra decrypts, and put out of action by air strikes. Yet the local counter-attacks mounted by German forces in the line, above all against the paratroopers east of the Orne, were so formidable as to inflict devastating casualties upon the British paratroopers, and finally to crush 51st Highland’s attack within hours of its inception on

11 June. The Germans had now deployed their 346th and 711th Divisions alongside elements of 21st Panzer and 716th on this right flank. 5th Black Watch, advancing into their first action at 4.30 a.m. that morning, suffered 200 casualties in an attempt to reach Bréville. ‘Every man of the leading platoon died with his face to the foe,’ recorded the divisional history proudly.

2

Yet General Gale, commanding 6th Airborne, concluded that it was essential to seize the village to close a dangerous gap in his own perimeter. The next night, the 12th Battalion, Parachute Regiment, in a brilliant sacrificial battle, gained Bréville at a cost of 141 casualties among the 160 men with which the unit advanced. The German 3rd/858th Regiment, which was defending the village, was reduced from 564 men to 146 in three days of fighting. Between the 11th and the 13th, other elements of 51st Highland Division sought to push southwards towards Sainte Honorine. But after a bitter series of to-and-fro actions in which every temporary gain was met by fierce German counter-attack, the British attack east of Caen petered out. The lightly-armed parachute battalions were exhausted and drained of men and ammunition. 51st Highland was unable to make progress.

‘The fact must be faced,’ declared the divisional history, ‘that at this period the normally very high morale of the Division fell temporarily to a very low ebb . . . A kind of claustrophobia affected the troops, and the continual shelling and mortaring from an unseen enemy in relatively great strength were certainly very trying . . .’

3

For the enemy also, the struggle east of the Orne remained an appalling memory. Corporal Werner Kortenhaus of 21st Panzer saw four of his company’s 10 tanks brewed up in five minutes during the attack on the château at Escoville on 9 June. Again and again the Mk IVs crawled forward, supporting infantry huddled behind the protection of their hulls as they advanced into the furious British mortar and shellfire. But when the tanks reversed they were often unable to see behind them, and rolled over the terrible screams of the injured or sheltering men who lay in their

path. A wounded panzergrenadier cried for his mother from no man’s land all one night in front of their position. Kortenhaus, trying to sleep beneath his tank, woke in the morning to find the tunic that he had laid on the hull when he dismounted was shredded by shell fragments. The bombardment seldom seemed to pause.