Overlord (Pan Military Classics) (25 page)

Read Overlord (Pan Military Classics) Online

Authors: Max Hastings

At the divisional commander’s briefing for the withdrawal, Lieutenant-Colonel Goulburn recorded the reasons given: ‘Firstly, 50 Div attack towards Longreves-Tilly, which commenced this morning, has made very little progress. Secondly, 2 Panzer Division has been identified on our front and it would appear that unless

we can form a firm base back on our centre line with at least an infantry brigade (which we haven’t got), he could cut off our communications, work round us and attack us from any direction.’ Early on the evening of the 14th, a heavy German attack on 22nd Armoured Brigade’s ‘box’ at Tracy-Bocage was repulsed. In its aftermath, the Germans were unable to impede 7th Armoured’s disengagement and retreat under cover of darkness. They withdrew four miles to positions east of Caumont, their supporting infantry slumbering exhausted on the hulls of the Cromwells, in many cases too far gone to waken or to dismount even when they reached the safety of their new harbours.

By any measure, Villers-Bocage had been a wretched episode for the British, a great opportunity lost as the Germans now closed the gap in their line. As Second Army reviewed the events of the past four days, it was apparent that the Germans had handled a dangerous situation superbly, while XXX Corps and 7th Armoured division had notably failed to meet the responsibilities that had been thrust upon them. On 10/11 June, the division had begun its attack led by tanks widely separated from their supporting infantry. When they encountered snipers and pockets of resistance manned by only handfuls of Germans, the entire advance was blocked for lack of infantry close at hand to deal with them. High explosive shells fired by tanks possessed negligible ability to dislodge well dug-in troops, although invaluable in suppressing enemy fire to cover an infantry advance. When tanks met infantry in defensive positions supported by anti-tank weapons, their best and often only possible tactic was to push forward their own infantry within a matter of minutes to clear them, supported by mortars. Yet again and again in Normandy, British tanks outran their infantry, leaving themselves exposed to German anti-tank screens, and the foot soldiers without cover for their own movement under fire. The suspicion was also born at 21st Army Group, hardening rapidly in the weeks which followed, that 7th Armoured Division now seriously lacked the spirit and determination which made it so formidable a formation in the desert. Many of its

veterans felt strongly that they had done their share of fighting in the Mediterranean, and had become wary and cunning in the reduction of risk. They lacked the tight discipline which is even more critical on the battlefield than off it. The Tiger tank was incomparably a more formidable weapon of war than the Cromwell, but the shambles created by Wittman and his tiny force in Villers-Bocage scarcely reflected well upon the vigilance or tactics of a seasoned British armoured formation. Responsibility for the paralysis of purpose which overcame XXX Corps when 7th Armoured’s tanks lay isolated at Tracy-Bocage after their initial withdrawal had to rest with its commander, General Bucknall, an officer henceforth treated with suspicion by Dempsey and Montgomery. Dempsey said:

This attack by 7th Armoured Division should have succeeded. My feeling that Bucknall and Erskine would have to go started with that failure. Early on the morning of 12 June I went down to see Erskine – gave him his orders and told him to get moving . . . If he had carried out my orders he would not have been kicked out of Villers-Bocage but by this time 7th Armoured Division was living on its reputation and the whole handling of that battle was a disgrace.

10

Yet the men of 7th Armoured Division bitterly resented any suggestion that, in the Villers battle, they had given less than their best. It was enormously difficult to adjust their tactics and outlook overnight to the new conditions of Normandy after years of fighting in the desert. They were newly-equipped with the inadequate Cromwell, which many of their gunners had scarcely test-fired, after fighting with Shermans in North Africa. There had been spectacular acts of individual heroism, many of which cost men their lives. The 1/7th Queens, especially, had fought desperately to hold the town. For those at the forefront of 22nd Armoured’s battle, it was intolerable to suggest that somehow an easy opportunity had been thrown away through any fault of theirs. The German achievement on 13/14 June had been that, while heavily

outnumbered in the sector as a whole, they successfully kept the British everywhere feeling insecure and off-balance, while concentrating sufficient forces to dominate the decisive points. The British, in their turn, failed to bring sufficient forces to bear upon these. It seems likely that Brigadier Hinde, while a superbly courageous exponent of ‘leading from the front’, did not handle the large brigade group under his command as imaginatively as might have been possible, and higher formations failed to give him the support he needed. It is remarkable to reflect that the men on the spot believed a single extra infantry brigade could have been decisive in turning the scale at Villers, yet this was not forthcoming. Some 7th Armoured veterans later argued that Montgomery and Dempsey should have taken a much closer personal interest in a battle of such critical importance. For whatever reasons, the only conclusion must be that the British failed to concentrate forces that were available on the battlefield at a vital point at a critical moment of the campaign.

A sour sense, not of defeat, but of fumbled failure, overlay the British operation on the western flank. On 11 June, while 7th Armoured was probing hesitantly south, on its left flank the 69th Brigade of 50th Division was hastily ordered forward to exploit what was believed to be another gap in the German line, around the village of Cristot. Lieutenant-Colonel Robin Hastings of the 6th Green Howards was mistrustful of the reported lack of opposition – he anyway lacked confidence in his elderly brigadier – and was no more sanguine after his battalion had waited three hours for transport to its start-line. When the Green Howards moved off, two companies up, they were quickly outdistanced by their supporting tanks of the 4th/7th Dragoon Guards, who raced forward along through the orchards. They failed to observe the hidden positions of panzergrenadiers of 12th SS Panzer, who had been rushed forward to secure the Cristot line in the hours since the British reconnaissance. Lying mute after the passage of the tanks, the SS poured a devastating fire on the Green Howards advancing through the corn, while anti-tank guns disposed of the British

armour from their rear. Only two of the nine Shermans escaped, and the advancing infantry suffered appallingly.

With one company commander dead and the other wounded, Hastings’s B and C Companies were pinned down. He ordered A to move up on the right and attempt to outflank the enemy. When he himself began to go forward to sort out B and C, his battalion headquarters came under such heavy fire that he was compelled to call up D Company, his last reserve, to clear the way ahead. CSM Stan Hollis, whose courage had done so much for the battalion on D-Day, was now commanding a platoon of D. As they advanced up a sunken lane edged with trees towards the enemy, they came under fierce fire from a German machine-gun. Hollis reached in his pouch for a grenade and found only a shaving brush. Demanding a grenade from the man behind, he tossed it before he realized, to his chagrin, that the had failed to pull the pin. A second later, he concluded that the Germans would not know that and charged them, firing his sten gun while they were taking cover from the expected explosion.

Hastings found that A and B Companies had joined up amid the burning British tanks, one turning out of control in continuous circles between the trees. They gathered the German prisoners and pressed on. Then A Company commander was killed, and the attack was again pinned down. The Green Howards had lost 24 officers and suffered a total of 250 casualties. ‘I think there’s a lot of work for you to do, padre,’ said Hastings wearily to Captain Henry Lovegrove, who won a Military Cross that day. The padre searched the hedges and ditches around Cristot for hours. He became a smoker for the first time in his life after a few horrific burials. Lacking armoured support and an artillery fire plan, the Green Howards could not hold their ground against German counter-attacks. Bitterly, Hastings ordered a withdrawal. The SS immediately retook possession and by nightfall were counterattacking towards the British start-line on Hill 103.

Hastings remained bitter about the losses his men had sustained in an attack that he believed was misconceived – that was

simply ‘not on’ – a fragment of British army shorthand which carried especial weight when used at any level in the ordering of war. Before every attack, most battalion commanders made a private decision about whether its objectives were ‘on’, and thereby decided whether its purpose justified an all-out effort, regardless of casualties, or merely sufficient movement to conform and to satisfy the higher formation. Among most of the units which landed in Normandy, there was a great initial reservoir of willingness to try, to give of their best in attack, and this was exploited to the full in the first weeks of the campaign. Thereafter, following bloody losses and failures, many battalion commanders determined privately that they would husband the lives of their men when they were ordered into attack, making personal judgements about an operation’s value. The war had been in progress for a long time; now, the possibility of surviving it was in distant view. The longer men had been fighting, the more appealing that chance appeared. As the campaign progressed, as the infantry casualty lists rose, it became a more and more serious problem for the army commanders to persuade their battalions that the next ridge, tomorrow’s map reference, deserved of their utmost. Hastings was among those who believed that an unnecessary amount of unit determination and will for sacrifice was expended in minor operations for limited objectives too early in the campaign. The problem of ‘non-trying’ units was to become a thorn in the side of every division and corps commander, distinct from the normal demands of morale and leadership, although naturally associated with them.

EPSOM

The debacle at Villers-Bocage marked, for the British, the end of the scramble for ground that had continued since D-Day. The Germans had plugged the last vital hole in their line. Henceforward, for almost all the men who fought in Normandy, the principal memory would be of hard, painful fighting over narrow strips of wood and meadow; of weeks on end when they contested the same battered grid squares, the same ruined villages; of a battle of attrition which was at last to break down Rommel’s divisions, but which seemed at the time to be causing equal loss and grief to the men of Dempsey’s and Bradley’s armies.

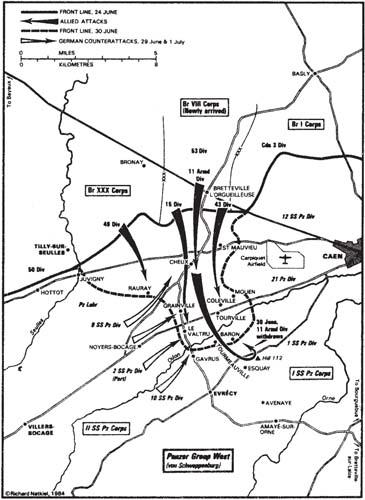

In the days following Villers-Bocage, unloading on the beaches fell seriously behind schedule in the wake of the ‘great storm’ of 19/23 June, which cost the armies 140,000 tons of scheduled stores and ammunition. Montgomery considered and rejected a plan for a new offensive east of the Orne. With the remorseless build-up of opposing forces on the Allied perimeter, it was no longer sufficient to commit a single division in the hope of gaining significant ground. When Second Army began its third attempt to gain Caen by envelopment, Operation EPSOM, the entire VIII Corps was committed to attack on a four-mile front between Carpiquet and Rauray towards the thickly-wooded banks of the river Odon. Three of the finest divisions in the British Army – 15th Scottish, 11th Armoured and 43rd Wessex – were to take part, under the command of Lieutenant-General Sir Richard O’Connor, who had made a brilliant reputation for himself leading the first British campaign in the western desert. A personal friend of Montgomery since their days as Staff College instructors together in the 1920s, O’Connor had been captured and spent two years languishing in an Italian prisoner-of-war camp. This was to be his first battle since Beda

Fomm in 1941. Early on the morning of 26 June, 60,000 men and more than 600 tanks, supported by over 700 guns on land and sea, embarked on the great new offensive: ‘The minute hand touched 7.30,’ wrote a young platoon commander of the King’s Own Scottish Borderers:

Concealed guns opened from fields, hedges and farms in every direction around us, almost as if arranged in tiers. During short pauses between salvoes more guns could be heard, and right away, further guns, filling and reverberating the very atmosphere with a sustained, muffled hammering. It was like rolls of thunder, only it never slackened. Then the guns nearby battered out again with loud, vicious, strangely mournful repercussions. Little rashes of goose-flesh ran over the skin. One was hot and cold, and very moved. All this ‘stuff’ in support of us! . . . So down a small winding road, with the absurd feeling that this was just another exercise.

1

In the first hours, VIII Corps achieved penetrations on a three-mile frontage. But then, from out of the hedges and hamlets, fierce German resistance developed. Some of the great Scottish regiments of the British army – Gordons, Seaforths, Cameronians – began to pour out their best blood for every yard of ground gained. Lieutenant Edwin Bramall of the 2nd KRRC, later to become professional head of the British army, observed that a battalion of the Argylls which infiltrated forward in small groups by use of cover reached their objectives with modest casualties. But the great mass of the British advance moved forward in classic infantry formation: ‘It was pretty unimaginative, all the things that we had learned to do at battle school. A straightforward infantry bash.’

2

That evening, the young platoon commander of the KOSB wrote again: