Owls Aren't Wise and Bats Aren't Blind (28 page)

THE BADGER

The badger

(Taxidea taxus)

is nature’s steam shovel. Whereas other members of the weasel family have variously come to utilize the treetops, the land’s surface, and the water’s depths, the badger is fossorial, meaning burrowing or digging. Indeed, it is superbly equipped for subterranean life.

Badgers are found from Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and the Great Lakes states westward throughout most of the remaining lower forty-eight. Their range extends southward into parts of Mexico and northward into the western Canadian provinces.

With its wide, flat body, very short legs, and grayish brown coat, a hunkered-down badger very much resembles a doormat, albeit one with a head sporting black and white facial markings. From two to two and a half feet long, badgers are sturdy creatures that weigh as much as twenty-five pounds.

In company with skunks, badgers seem unlikely relatives of the svelte, swift weasel, fisher, marten, or mink. However, they bear the unmistakable hall-marks of their kin, including the anal scent glands.

Badgers have developed several adaptations marvelously suited to such subterranean proclivities as tunneling after ground squirrels, prairie dogs, mice, and other small rodent prey; scooping out burrows for daytime sleeping; and digging themselves rapidly out of sight if danger threatens.

Foremost among these adaptations is a set of incredibly long, strong front claws. A full two inches long, they would do justice to an animal many times the badger’s size. These are coupled with another adaptation, webbed front toes. Thus the badger, using its powerful front limbs, can rip out the soil with its great claws and hurl the loosened earth backward with its scooplike front feet. In earth suited for digging, a badger, clouds of dirt flying behind it, can dig its way out of sight in about two minutes!

A third adaptation is a transparent inner eyelid, called a nictitating membrane. This can be drawn across the eye when necessary to keep dirt out, enabling the badger to see even when digging furiously.

People who have never encountered a badger—if they think about badgers at all—tend to regard them as relatively placid and benign creatures. Those who have had dealings with badgers know better.

Probably much of this image can be traced to Kenneth Grahame’s great classic,

The Wind in the Willows.

In the utterly charming world that Grahame constructed, Mr. Badger is a gruff but kindly individual, possessed of great wisdom and integrity. Badgers are gruff, all right, but kindly they are not! A nineteenth-century writer, John Clare, summarized the badger’s disposition with great accuracy: “When badgers fight, then everyone’s a foe.”

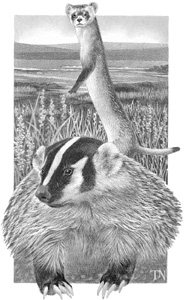

Black footed ferret

(top)

; badger

Unlike European badgers, which often live as an extended family in a warren of burrows called a

sett,

American badgers are solitary creatures except for a brief period of mating. In keeping with their hermitic nature, badgers are extremely displeased by any invasion of their rather outsized personal space, which they will defend aggressively.

If a human, a would-be predator, or even another badger approaches too closely, the response is usually a series of ferocious growls and hisses, backed up by an impressive show of teeth—and by all accounts, the sound levels produced by a badger angry at being caged are truly fearsome!

This display is no mere bluff. Badgers are noted for their courage, ferocity, and exceptional strength, as many larger creatures have learned to their sorrow. Badgers regularly whip dogs several times their size and not infrequently kill them.

Complicating matters for anything that attacks a badger is its thick, tough, exceptionally loose hide. If, for instance, a predator seizes a badger by the neck, the loose hide permits the badger to turn and savage its tormentor. As a result, adult badgers have almost no serious natural enemies, although wolves and cougars probably preyed on them at one time. Nowadays, automobiles represent the worst threat to badgers, which seem to be no more afraid of them than of other enemies.

Badgers, on the other hand, prey widely on many species. Besides a variety of rodents—a staple of their diet—badgers happily consume raccoons, armadillos, larvae of bees and wasps, snakes, lizards, birds’ eggs and young birds, frogs, crayfish, and sometimes carrion. In addition, they will dig out the dens of foxes and coyotes and devour their pups. Thus does the image of the sedate, kindly badger break down!

Except for a mother with young, badgers seldom spend two days in a row in the same den. Instead, these mostly nocturnal mammals simply dig a new burrow wherever they find themselves at dawn. Although badgers are generally active throughout the winter, they have no qualms about fashioning a cozy burrow and staying there for several days to wait out a spell of especially bitter weather.

Badgers breed in late summer; as in most mustelids, implantation is delayed for several months, and the young aren’t born until the following spring. The cubs, usually two or three per litter, are born blind and with very little fur.

By late spring, after being weaned and then introduced to meat brought by their mother, the cubs travel with her for several weeks, learning to forage. By summer, however, they either leave their mother voluntarily or are driven off to lead the mostly solitary lives that seem well suited to these markedly short-tempered animals.

THE BLACK-FOOTED FERRET

The black-footed ferret

(Mustela nigripes)

holds the dubious distinction of being the only endangered species among North American mustelids. Weighing approximately one and a half to two and a half pounds, this marten-sized weasel closely resembles the steppe polecat

(Mustela eversmanni)

of Eurasia. Mostly yellowish brown, it has a lighter face with a black mask across the eyes and forehead and a black-tipped tail. Further, as both the common and scientific names indicate (

nigri,

black, plus

pes,

foot), all four feet are black.

All other North American members of the weasel family seem to be at least holding their own throughout wide portions of their range, so how did this distinctively marked animal end up in such a precarious situation? The answer, in simplest terms, is overspecialization.

Principally nocturnal, the ferrets prey very heavily, sometimes almost exclusively, on prairie dogs; when these rodents disappear, so do the ferrets. Over a long period, several things have drastically reduced prairie dog numbers throughout the ferret’s range.

First, much prairie was converted to agricultural uses unsuitable for prairie dog habitat. Second, many prairie dog colonies have been eliminated by poisoning, since the rodents were considered a nuisance. And third, prairie dogs began dying from sylvatic plague, which is the animal equivalent of bubonic plague—the infamous Black Death of the Middle Ages.

By 1985, only eighteen live black-footed ferrets were known to exist, and it was feared that they would die from distemper (actually, it was later found that sylvatic plague was a greater threat). At that time, a decision was made to live-trap them and try to raise a captive population; if their numbers increased greatly, it might then be possible to reintroduce some to the wild.

Fortunately the eighteen captive ferrets thrived and multiplied. As their numbers increased into the hundreds, efforts were made to reestablish them in the wild. Some attempts have failed, but the program has had good success in Montana and South Dakota. At present there are around 150 ferrets in the wild and about 350 in captivity. Although those numbers are encouraging, ferret experts caution that the future of wild populations is still very uncertain.

Besides its endangered status, the black-footed ferret is unusual in another way: together with the least weasel, it’s the only North American mustelid that doesn’t have delayed implantation. It does, however, have what is known as

stimulated ovulation.

This means that the female doesn’t ovulate until breeding by the male causes her to do so. The two to five young are born in June and disperse as adults in August.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, under the Endangered Species Act, has done an outstanding job of bringing the black-footed ferret back several long steps from the brink of extinction. As with some other endangered species whose numbers are increasing, however, it’s still too early to declare victory in the effort to save this important cog in the prairie ecosystem.

THE WOLVERINE

If skunks have widely been viewed with disfavor, the reputation of the wolverine

(Gulo gulo)

has been far worse. When I was growing up, stories in outdoor magazines and tales in books about the far north portrayed the wolverine as possessed of a demonic hatred of humans, abetted by a fiendish cleverness— in short, a devil in animal form. More enlightened thinking, combined with scientific observation, paints a rather different picture.

The second-largest member of the weasel family, the wolverine can weigh as much as sixty pounds. Admittedly, it’s a decidedly odd-looking creature; to paraphrase the famous description of the camel, the wolverine looks like a small bear designed by a committee.

With a bearlike head and body, the wolverine has a short, bushy tail that somehow looks like an afterthought. Its coat is thick and dark brown, except for a lighter band across the top of the head and a wide, yellowish stripe along each side; these stripes start at the front shoulders and merge at the tail, much like the stripes on a skunk.

The principal range of the wolverine is the far north, from Alaska across Canada and into that nation’s farthest Arctic reaches. Wolverines are also found southward through British Columbia into Idaho and perhaps a few other pockets in the United States.

Unfortunately, not enough is known about remaining wolverine habitat in the lower forty-eight states. Money for wolverine research is scarce, and much needs to be learned about where they live and how many are left. What is known is that wolverines were once found much more widely in the United States, including the Midwestern and Eastern states. Ironically, there is absolutely no evidence that wolverines ever inhabited Michigan, which is known as the Wolverine State.

Wolverine

The wolverine’s diabolical reputation is based largely on a combination of tall tales and misinterpreted facts. The accounts of wolverine-as-devil usually go something like this:

A trapper runs his trapline from a cabin in the far northern wilderness. One day a wolverine discovers the trapper and instantly acquires a dire hatred of the man. The wolverine then begins checking the trapline ahead of the trapper, killing and eating the catch in order to drive the trapper away. Desperate, the trapper attempts to trap or shoot the wolverine, but to no avail; with fiendish cunning, the wolverine continually eludes him.

One day the trapper returns to his cabin to find that the wolverine, as further proof of its diabolical nature and all-consuming hatred, has broken into the cabin and eaten or destroyed the trapper’s winter supplies. The trapper is forced to give up and return to civilization, the victim of a supernatural adversary.

No doubt there is considerable truth to at least some of these tales, but the trapper’s interpretation of the facts are wildly inaccurate. The actual story is probably as follows:

The wolverine evolved as a denizen of an extraordinarily harsh climate. Lacking particularly good eyesight and hearing, this mammal is nonetheless wonderfully adapted to its home in the far north. These adaptations include a marvelously keen sense of smell, great endurance, and immense strength for its size; indeed, many consider the wolverine and badger to be, pound for pound, the strongest of all North American mammals.

The wolverine, to survive in such a harsh environment, became a hunter and scavenger in the summer, caching quantities of food against the long winter, and primarily a scavenger during the winter. Using its exceptional sense of smell, the wolverine could detect its caches and the remains of old wolf or bear kills beneath several feet of snow.

One day a trapper moved into territory inhabited by wolverines. He built a cabin and, like the wolverine caching food for the winter, stocked the cabin with enough staples to see him through until spring. Then, on snowshoes, he set his traps along a circuit covering several miles.