Oxfordshire Folktales (3 page)

Read Oxfordshire Folktales Online

Authors: Kevan Manwaring

![]()

T

HE

W

HITE

H

ORSE

OF

U

FFINGTON

Come to the Horse Fair-O – have you a scrape and thrill!

Come to the White Horse, stabled on Uffington Hill.

It was the time of the Scouring of the Horse, a great fair that took place every seven years on Uffington Hill. The local lord himself had funded it, though much did he rue the fact, complaining about the state of the economy, taxes and poor harvests. But the spirit of the people to celebrate could not be suppressed, especially when they’d had to wait so long; long enough for legs to grow, and tales in the telling of the previous fair. Littl’uns who’d grown up listening to what the grown-ups spun were now eager to discover the magic for themselves. Would it be real, or moonbeams on the chalk? Well the day had finally come…

Uffington Fair is always a very lively affair – officially lasting for three days – although the revelry often continues before and after with the quaffing of much ale, the feasting, the cheese-rolling down into The Manger, stalls selling gewgaws and local wares, wrestling, dancing, tests of strength, the sharing of news and views, and, of course, the Scouring of the Horse. The villagers took great pride in this, and Betty was one of them – a local lass, this was the second Scouring she could remember. She was conceived at one, fourteen years ago, so her folks remind her, much to her embarrassment: she was an ‘Uffington gal, thru and thru,’ her Dad said. The fair had always seemed magical to her, with its many sights and wonders, but especially this year when she felt… different, and had taken great care in preparing her outfit, a lovely clean white dress with ornate bonnet, her best shoes, her hair done just so, and her face ‘as fresh and comely as a May morning’, as her Granny said. Holding a garland of flowers, she had proudly joined in the procession to the Horse at dawn along with the whole village – apart from Granny, whose legs weren’t like they used to be.

Bill the butcher led the way, beating his pigskin drum in solemn manner, his black tricorne hat sporting a pheasant feather, ‘like the cock o’ the morn,’ someone giggled, until elbowed into respectful silence.

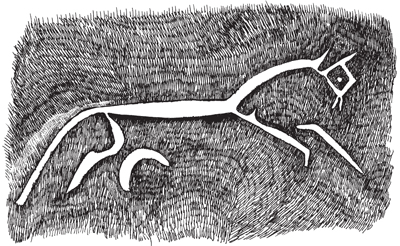

They gathered in a great circle round the chalk figure – over three hundred feet in length – which was carved into the side of the Downs. They stood overlooking the Vale of the White Horse, slowly emerging from the mist as though from the dawn of time.

The drumming stopped and the priest said a few words, blessing the Scouring in the name of the Lord; and then they set to work, removing any weeds that had grown in the chalk over the last few years. It was said if the Horse grew too hairy, the harvest would falter: ‘No grain in the barn; no butter for the bairn.’ And so the villagers took the Scouring seriously – as long as the White Horse shone down upon them ‘luck would fill the Vale’. So the old ones said, and so the young ‘uns followed. And so it always had been – longer than any could remember.

As Betty pulled out the tufts, a laugh caught her attention; it was John, the blacksmith’s son, with his dark lick of hair. He gave her a wink, and she blushed even more.

They spent the rest of the Scouring coyly flirting with each other. It was like playing in the smithy – Betty knew it was perilous and she could easily get her fingers burnt, but she could not resist. There was something about the day, the time of year, and the time of her life. Like the verdant land around her, she felt like she was … waking up.

The June sun was burning away the mist to reveal fields brimming with new growth. With so many hands at work, the Scouring was soon complete. A festival breakfast awaited them – warm bread and strong cheese, spring onions and last year’s apple chutney – which they took on the flanks of the hill. A cool jug of cider was passed around and for the first time, handed to Betty, who warily took a sip and coughed. John laughed his easy laugh, accepted it from her and downed a draught, wiping the back of his hand with a smack of his lips. They smiled at each other as someone struck up a fiddle.

‘Come on!’ John led them, laughing, to the delights of the fair.

* * *

What a day it had been! They were deliciously weary from it now – all the delights they had seen and savoured, the rickety fairground rides, the side-stalls, the sugary treats, the buzz of conversation, the dancing and foolery. With a satisfied sigh, they wandered away from the fair, which was now being packed away.

The villagers lingered on the hillside, savouring the last golden drops of the day.

A little awkward, the young couple held hands and walked away from the crowd.

From the ramparts of the ‘castle’ – the earthwork above the Horse – they watched the sun set. Below, the Horse gleamed in the silver light of the moon which rose as the sun fell.

Around them they sensed the gaggles of villagers, making merry. Louder than all, they could hear old Lob, the local teller in his flow now he was lubricated with cider. He was declaiming on his favourite subject of horse lore: ‘If mares slipped their foals, a black donkey would be run with them to cure evil; if a donkey was unavailable then a goat could be used the same way!’ Laughter carried across the hillside.

‘What about different coloured horses, Lob – what do you make of that?’ someone piped up, with a nudge and a wink to a friend.

‘A good horse is never a bad colour.’ Sounds of affirmation, though one scratched his head.

‘A horse with a white flash on its forehead is lucky, as is a white-footed one, but if it has four white feet they should be avoided, it’ll be unlucky with a surly humour.’

Someone commented, ‘We’d best be careful then, with the White Horse so close!’ Lob rubbished this idea.

‘Of all the horses, a pure white horse is the most auspicious – but its magic is strong, and so it is wise to cross ‘uns fingers, and keep ‘em crossed ‘til ye see a dog.’ Nearby a dog barked, and everyone laughed with relief.

Snuggled on his coat, John and Betty lay in the twilight, holding one another. Betty tingled all over. This was the first time she’d been close to a man. The first time she had slept outdoors. But since half the village was there, it felt safe and acceptable to do so. It was common for them to sleep out on Horse Fair Hill on this special night. Many a good memory had been forged on its flanks, and passed down the generations, making the young ‘uns especially keen to have their own ‘experience’.

The cider, the music, the stars – all swirled in her mind. Betty felt like she could float off, but John’s arms softly held her to the earth. His gentle words soothed her, his rough hand smoothing her hair.

As he cradled her in his arms, John told her how on moonlit nights just like this, the Horse would come down to feed in the Manger – the meadow in the hollow of the hill beneath them. This made Betty shiver and she was glad of his strong arms around her. It had been a rich day in many ways – she’d had a bit too much to eat and drink, and her head was whirling as she found herself slipping into a deep slumber, the sound of Uffington Fair drifting on the night air.

* * *

The distant beat of the drums carried her deep into the hillside which seemed to open up and swallow her, until she felt like the land itself. She felt the stirring of every living thing – beetle and ladybird, mole and vole, rabbit and hare, fox and badger, swine and stag – moving above her and inside her. So much life! Sowing and growing, mating and decaying – an endless cycle that stretched back a long, long time.

The drumming became the thudding of horse hooves, and suddenly she was above ground, galloping along – a white horse, as pale as moonlight! She ran free across the Downs, along the Ridgeway, its ancient paths glowing in the silver light. Whinnying with joy, she came out onto the open land above the White Horse – which, strangely, was not there. Only a clean swathe of grass could be seen. Her nostrils quivered and she snorted a plume of breath. The landscape was the same, but different. The Castle was surrounded by a palisade of sharpened timbers, dark spikes against the lights of a village inside. The strong wooden gates creaked open and out processed a line of people holding torches, led by drummers and priests and priestesses in white robes, adorned by oak leaves and flowers. They made their way to the side of the hill and the drumming suddenly fell silent.

As one, they watched as the moon rose in her fullness, flooding the Manger with unearthly light. The robed ones began to speak in a strange tongue that sounded vaguely familiar.

Betty could catch the odd word, which echoed in the back of her mind like a pebble dropped in a deep well. They turned to her and for a moment she was frightened, thinking they had spotted her, the trespasser; but they hailed her by a strange name: ‘Epona!’ The tribe came forward and placed offerings at her feet – the bounty of the land. And then the priesthood oversaw the cutting of the turf. By their direction, the shape of the Horse was carved out of the hillside, revealing the chalk beneath. The design was stylised and elegant, and resembled the intricate ornaments some wore, or the tattoos revealed as men stripped down to their waists to work on the Horse. Finally, it was complete and the moon-glow bestowed upon it an unearthly sentience. Betty felt the spirit of her horse pour into it. The Goddess was happy and lay upon the bed they had prepared for her. She felt soothed by the songs the tribe sang, the fellowship that flowed around the gathering – a circle of love, binding them together.

* * *

Betty awoke, blinking, yawning and rubbing her eyes. The ghost of the sun could be sensed through the mist, which lay like a white sea over the Vale. Somewhere, a cock crowed and around her lay the huddled shapes of villagers, looking like no more than bundles of clothes by smouldering fires.

She was a little disorientated at first, and unsettled by her vivid dream. But it was all right. John still held her in his solid arms, snoring lightly.

Below her, the White Horse of Uffington lay; a reassuring permanence on the landscape. It was old, very old, and yet it had survived. The people of the Vale of the White Horse had preserved it for all of these years; beyond living memory – but not the memory of the land.

Around her, villagers were awakening and returning to their homes, to their chores and tasks. Uffington Fair was over for another seven years, but Betty would remember it for the rest of her life. She had been changed by her night on the hill. The horse inside her had woken up, had tasted the Manger, and would not be put back in its stable.

Beside her, John stirred, yawned and smiled. He brushed down his coat and put it round her shoulders and off they set.

‘Well, that’s it then; back to the forge for I,’ said John. ‘May the Horse bring us luck.’

Both were lost in their thoughts, the ghost of the night lingering.

Seven years! Who knows what life will bring them by then?

Betty knew and she walked with a confident gait down the hill, arm-in-arm with John, her bridegroom-to-be. Although, he did not know it yet.

![]()

The White Horse of Uffington is an iconic image of the area. Whenever I travel by train between London and the West County I always notice it. When I have returned from a trip abroad it is a heartening sight – I know I am back in England, its very heart. I always breathe a sigh of relief when the claustrophobic sprawl of the capital and its hinterland gives way to a gentler, greener landscape. Once the threshold of Old Father Thames is crossed things become more mythic. Entering the Vale of the White Horse, the countryside widens out into a broad valley, the hills of the Ridgeway rising to the south. The White Horse feels like a threshold guardian of sorts, and perhaps that was the intention of the original makers. It was long believed King Alfred cut it to celebrate his victory over the Danes – in that role

he

was being England’s threshold guardian – but the horse actually dates back to 2800

BCE

. It might well have marked the tribal territory of the area, or had some religious significance: a horse cult; or horse tribe. I like to imagine that J.R.R. Tolkien, the county’s greatest storyteller, would have been inspired by the sight to create the horse lords of Middle Earth, the Rohan – perhaps while standing on Faringdon Folly (on a clear day, you can see the Horse from there), which is rather like Saruman’s tower, Isengard. The iconic chalk figure stirs the imagination (as it did for my friend Peter Please, who wrote

The Chronicles of the White Horse –

a children’s novel, accompanied by an album of quintessentially English folk music). Although no actual folk tale exists, I took the rags of folk lore connected to it – chiefly around the Scouring Fair, which used to be held every seven years – and wove them into a story which I hope evokes the spirit of place. Like young Betty, I too have slept out there (within Uffington Castle itself – the sacred flanks of the White Horse is not a place to pitch a tent). I cannot remember the dreams I had there, but I imagine they were vivid. As a young man I came across the notion that by sleeping or meditating at sacred sites we can ‘time travel’ and catch a glimpse of their past, perhaps tapping into ‘place memory’. Do the events that happen at a site become recorded somehow? Certainly, battlefields feel that way, and haunted houses. And so I adopted this ‘shamanic’ method of narrative retrieval.

Any location can be explored in this way – dreaming the land – there’s certainly no harm in trying, and even if no apparent evidence remains of its ‘story’ we can perhaps retrieve fragments with our ‘dream-soundings’.

Certainly, listening to the Earth is a good place to start. How else can we tell the deeper story of a land? As with the cutting of the Horse into the chalk beneath the turf, the deeper you go, the more is revealed. If we limit ourselves to what is only visible on the surface (or in books and archives; virtual or otherwise) then we can miss so much.

The real story is always the one right under our feet.