Oxfordshire Folktales (7 page)

Read Oxfordshire Folktales Online

Authors: Kevan Manwaring

This was her final act of witchery â the last drops of her magic leaked from her as she hardened into an elder tree, rooted to the ground.

And there they have stood for a long, long time â King, Knights, King's Men and Crone â seeing wilful men and wise women come and go. A hard lesson in pride; yet few are willing to learn it.

In 1859, it was recorded that folk from Wales took chippings from the Stones to âkeep the Devil off'. A man was offered one pound for a fragment at Faringdon Fair. The beleagured King's Stone was fenced off between the two world wars, as conscripted troops would chip a slice of stone away to carry with them. Legend has it that this gave them protection in battle.

Yet despite such vandalism, the stones remain, weathering the ages. Now folk come from far and wide to marvel at them, measure and dowse, worship and make strange sounds. But local folk, who know best, see them as special in their own âsimple way'. One day, at the turn of the old century, a folklorist called Arthur Evans reported that one of his informants, a local landowner, met one of his labourers on Good Friday: âWhere do you think I be going?' the man asked, before continuing, âWhy I be agoing to the King-stones, for there I shall be on holy ground.'

![]()

The ancient Rollright Stones are a magical place, high upon a ridge overlooking the Cotswolds â a lonely, eerie site. Like iron filings to a magnet, it has attracted stories. The rich combination of folklore was easy to weave into a tale. I have visited it many times over the years â celebrating the turning of the wheel either alone or in a group. I recommend making pilgrimage to it (for it is a sacred site) at different times of year and at different times of day, to get the full effect of this remarkable sacred landscape. Spend time not only amongst the impressive ring of the King's Men; but also with the twisted menhir of the King's Stone â like a frozen figure striding forth â and with the Whispering Knights, down in the far corner of the field by themselves, where it was said local girls would go to hear the name of their future sweetheart whispered. Once, I sat inside this ancient burial chamber and felt myself being dragged back through the millennia. It was with some effort that I returned to the âpresent day'. These stones have their own gravity. Standing quietly by themselves just off the obscure back road, their modest presence has a magic with roots that go deep into the land.

![]()

G

EOFFREY

THE

S

TORYTELLER

The stooped, robed man with the whitening beard had been a familiar figure around the castle at Oxenford these last twenty-two years – so much so that nobody noticed as he slipped out a side gate and made his way, as quickly as his robes would allow, along the side of St George’s College. It had been his home for over two decades but on the morrow all this was about to change. The air was bitter and his breath came in white clouds. The snow beneath his feet was melting away in pockets, and the patches of grass that were revealed seemed to be the only colour in the wintry landscape.

Yet there, at the edge of the trees, was a sign to gladden his heart: snowdrops. Geoffrey bent to examine them, the first omen of Spring; so frail, yet so tough, to withstand the frosts, the biting winds, and the late snow.

He couldn’t remember the last time he had been truly warm.

The scriptorium was draughty and after two decades of scratching away on vellum with a goose feather quill, his hands complained – the cold got into his bones and made them ache. His one true pleasure was agony: writing.

How he loved to daydream and wander into other worlds. Some called it escapism – fanciful make-believe – but Geoffrey knew there was real value in reverie. All the facts he had read, the dusty dates, the places, the names, the long lineages, swirled around in his head like a flurry of snowflakes, until finally settling onto the blank parchment – his neat Latin script like crow feet in the snow; or the ancient runes and Ogham he had glimpsed. The fact he could read the heathen script he kept to himself. The old stones were fascinating, but were meant to be shunned by the likes of him.

A secular canon for twenty years – tomorrow he would be made a Bishop! The dedication in his last book had paid off to his old colleague Robert De Chesney, the new Bishop of Lincoln. Tomorrow, he would go to Lambeth Palace and be consecrated by Archbishop Theobald for ‘good service to his Norman masters’. Geoffrey suspected his consecration was more expedient than anything – as speaker of the old Brythonic tongue, he was probably chosen in an attempt to make the diocesan administration more acceptable in an age when Normans were not at all popular in the areas of Wales which they controlled. Owen Glendower’s rebellion was in full swing and he didn’t hold out his chances of succeeding in his role.

Yet secretly Geoffrey thrilled at the reports he heard of the rebel king’s rise to fame – it felt as though his stories had come true. His fellow countrymen – for was he not one of the Waleas, the ‘strangers’? (an ironic name for the indigenous inhabitants usurped by the invaders) – had taken to heart his History of the Kings of Britain –

Historia regum Britanniae

– his magnum opus penned thirteen years before. The stories of the Pendragon had most of all caught the imagination of all who read them and had made his name, so that folk now called him Galfridus Arturus. His own people would call him Geoffrey ab Arthur, which he preferred even more. Son of Arthur! Yet were not all British men ‘sons of Arthur’, and was not the story he told ‘the Matter of Britain’? It was the very soul of the land. When he thought about it, it stirred something within him. As he walked among the trees, he felt it beneath his feet as they crunched into the rigid mulch; in the freezing air; in the tinkling of an icy stream; in the caw of the rooks.

He thought he heard a whisper from the woods. He stopped and scanned the trees. Nothing. His imagination getting the better of him, again! He let out a wisp of breath; turned to continue – then nearly had his heart stopped as a roebuck bounded across his path. For a moment they were eye-to-eye, and Geoffrey caught a glimpse of his own silhouette in the buck’s dark orbs. It had seven tines upon each antler. Quickly, it disappeared back into the trees.

Geoffrey lent against a birch tree to catch his breath. His body shuddered into a bellow of laughter. It was good to laugh again – life in the castle was getting very serious of late. The endless Machiavellian machinations were exhausting: the infighting and back-biting; the jockeying for power, for favour, for influence.

Composed at last, he carried on along a small track he knew well enough to find, even when it was covered with a fresh fall of snow. He had walked here many times over the years to get some fresh air when life in the castle became stifling; to stretch his legs after sitting for too long, hunched over his desk, and to visit an old friend: Myrddin. Strictly speaking (and Merlin was a stickler for detail) that should be Myrddin Silvestris – Merlin of the Woods.

He stepped into the grove and there he was – the ‘ancient book’ he came to consult. The ghost of a smile played upon his lips. They would never guess this was his primary source!

Geoffrey stood before an ancient oak tree bulging with age. Only two of its main limbs remained, which grew either side of the hollow trunk like antlers. Here was truly the Rex Nemorensis – King of the Grove.

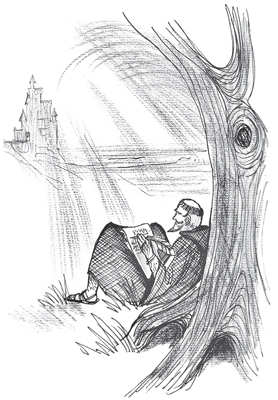

He would sit here, feeling his vertebrae against the ridges of the trunk, for hours, lost in thought. Sometimes he would climb inside and feel a part of the tree, especially when he nodded off and dreamt strange dreams. That’s when the whispers would come. It was here, a couple of years ago, that he received the ‘life of Merlin’. And twenty years ago, on a day he would never forget, he had first stumbled upon the tree and, in a burst of boyish excitement, tried to climb inside, slipped and banged his head. He ended up upside, his foot caught in the crack, the very image of the Hanged Man, as in those strange cards he had seen once when they were passed amongst the ladies of the court, smiling with amused curiosity at the figures and situations they recognised in each image. Here, hanging for a timeless time, he received the vision. The prophecies came to him then in a flash, the whole lot. For several days after, he hardly slept or ate at all as he feverishly recorded all that he could remember. Half of it didn’t seem to make sense, but he simply tried to transcribe rather than interpret.

Prophecies were popular at the time – they always are in uncertain times – and the book was published, copies going to the libraries of the rich. With this success under his belt, he was encouraged to write another. Geoffrey was at first bereft of inspiration for he could not say where such ‘voices’ came from. He had no more control over them than an epileptic does with his fits.

Then he remembered Myrddin and returned to the tree. This time, he was careful with his footing and managed, after some trial and error, to find a way to ‘hear’ the voice of the oak. Adopting a more methodical – and less hazardous – approach, he managed to note down the lineage he received, relating right back to Brutus. Every day he would return to the castle with a new scroll of beech bark upon which he had scribbled in Brythonic the words of the wizard. Then, in the scriptorium, he would set about translating them into polished Latin. The wealthy and powerful like to read about … the wealthy and powerful. When he had finished his ‘histories’ he dedicated it to Robert, Earl of Gloucester and Lord of Glamorgan – who was also the natural son of Henry I and a contender for the throne; Bishop Alexander of Lincoln, Waleran Count of Mellent; and King Stephen. It was a shrewd move that paid off. He had learnt in his time at court that flattery gets you everywhere.

Tomorrow, he would be made a Bishop – but whether it was a blessing or a curse he could not say. St Asaph’s was a tainted chalice, an obscure bishopric in the middle of nowhere. Perhaps they just wanted him out of the way. He wouldn’t miss the castle, or any of its inhabitants, whom Geoffrey had grown weary with.

Only his friend.

On this day, sacred to Saint Brighid, the festival the pagans call Imbolc, Geoffrey came to say farewell to Myrddin. The tree brooded darkly over him in the white wood. Emotion choked him, so that all he could utter was a terse, ‘Thank you’. He placed the rolled-up scroll, covered in wax to protect it from the damp, inside a slot in the tree’s split bough; then, laying his hand softly upon the rough bark one last time, he turned and walked away into the snow.