Pediatric Examination and Board Review (18 page)

Read Pediatric Examination and Board Review Online

Authors: Robert Daum,Jason Canel

(C) the child with viral croup is more likely to present in the middle of an upper respiratory infection (URI) than the patient with epiglottitis

(D) the child with viral croup cannot be distinguished from the child with epiglottitis by clinical criteria

(E) none of the above

10.

The classic clinical findings of viral croup are

(A) steeple sign, inspiratory stridor, low-grade fever, URI symptoms, barking cough

(B) steeple sign, high fever, dysphagia, rash, staccato cough

(C) thumb sign, inspiratory stridor, URI, dysphagia, barking cough

(D) thumb sign, high fever, expiratory wheeze, inspiratory stridor, staccato cough

(E) no radiographic findings, expiratory wheeze, and high fever

11.

Treatments for viral croup requiring supportive care in a hospital setting should include

(A) antibiotic coverage for possible superinfection

(B) humidified oxygen, racemic epinephrine, and corticosteroids

(C) oseltamivir and humidified oxygen

(D) intubation and IV antibiotics

(E) IV antibiotics for croup

12.

Pick the false statement from the following

(A) all patients with viral croup must be hospitalized because of the risk of airway obstruction

(B) all patients with epiglottitis must be hospitalized because of the risk of airway obstruction

(C) all patients with epiglottitis benefit from antibiotic therapy

(D) most patients with viral croup benefit from anti-inflammatory agents

(E) B and C

13.

Pick the false statement from the following

(A) patients with viral croup who have received racemic epinephrine may be discharged to home without a period of observation

(B) patients with viral croup may be sent home safely after receiving parenteral corticosteroids

(C) patients with epiglottitis respond little to racemic epinephrine and therefore it is not recommended for treatment

(D) patients with epiglottitis do not respond to corticosteroids sufficiently to warrant their use in the disease

(E) protecting the airway is of little concern in epiglottitis

14.

The ominous sign(s) of impending respiratory failure in a patient with viral croup is/are

(A) expiratory wheezes and rales

(B) inspiratory stridor and crackles

(C) muffled biphasic stridor

(D) expiratory wheezes and rhonchi

(E) coughing

ANSWERS

1.

(B)

Making the diagnosis of epiglottitis can be difficult. A high index of suspicion by the initial evaluating physician is imperative, especially in a young child. The patient typically presents with a sudden onset of fever, sore throat, drooling, and difficulty swallowing. Classically, the child appears toxic with temperatures that can reach 39-40°C. The patient typically prefers the position of maximal airflow, sitting forward with the neck hyperextended, chin forward. An urgent referral to otolaryngology or anesthesiology is required. The patient should be taken immediately to an operating room setting and gently anesthetized. After the induction of anesthesia, an upper airway evaluation can be performed. Routine examination of the pharynx should be deferred until anesthesia is induced because sudden, complete airway obstruction might result. In this case, time spent obtaining a neck radiograph would only delay evaluation and can increase the chance of further respiratory compromise.

2.

(C)

Epiglottitis (in the pre-Hib vaccine era) was caused almost exclusively by Hib and usually occurred between 1 and 5 years of age with a peak incidence in the third year of life and a slight male predominance. Since the introduction of the Hib vaccine, the epidemiology of epiglottitis has shifted. In the United States, it is no longer a disease of young children but rather a disease of teenagers and young adults. In the unvaccinated patient the likely culprit may still be Hib, to which antibiotic therapy should be targeted. For patients who are vaccinated or in older patients, antibiotic therapy should cover both Hib and

S aureus

.

3.

(B)

Anatomically, epiglottitis is not limited to the epiglottis. Thus

supraglottitis

is a more descriptive term. It is a cellulitis of all structures of the laryngeal inlet, including the aryepiglottic folds and arytenoid cartilages. The large potential space between the epithelial layer and the cartilage in these tissues allows the accumulation of inflammatory cells and edema during infection. As this potential space enlarges, the swollen epiglottis and adjacent structures begin to obstruct airflow through the laryngeal inlet during inspiration. Abrupt onset and rapid progression of airway symptoms are the hallmarks of epiglottitis. In the operating room the diagnosis can be made by direct inspection. If confirmed, an endotracheal tube should be introduced under direct vision and secured. After securing the airway and obtaining cultures in the operating room, the patient should be transferred to the ICU where mechanical ventilation is often needed to allow the child to be adequately sedated. Reinspection of the epiglottitis using a flexible bronchoscope can be easily performed and will guide appropriate timing of the removal of the endotracheal tube. In general, 48-72 hours of antibiotic therapy is sufficient for elimination of airway obstruction. Corticosteroids have no role in epiglottitis in small children. There may be some role for corticosteroids in opportunistic infections in older patients, especially when epiglottitis is of an uncommon etiology.

4.

(C)

Infectious diseases of the upper respiratory tract in children are common. Inflammatory diseases involving the larynx in the first 6 years of life include croup and epiglottitis. Croup is a viral infection of the larynx, trachea, and bronchi. In contrast, epiglottitis is a bacterial disease of the larynx that has been virtually eliminated in the United States by the introduction of the Hib vaccines. Since their introduction in 1991, all diseases caused by Hib have substantially decreased, from an incidence of 100/100,000 population to 0.3/100,000 population. However, in other countries where this vaccine is not available, Hib may still be an important cause of disease.

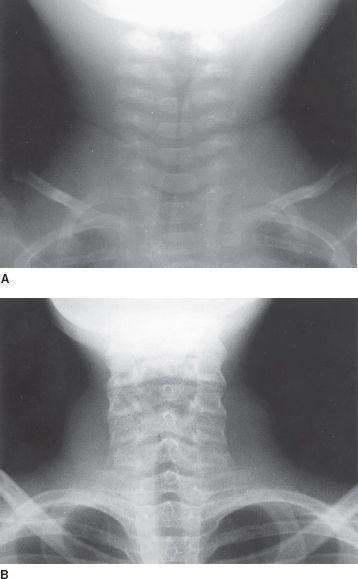

FIGURE 8-1.

The “steeple” sign of croup in a 1-year-old

(A)

and a 12-year-old

(B)

. (Reproduced, with permission, from Stone CK, Humphries RL. Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Emergency Medicine, 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008: Fig. 30-10A,B.)

5.

(D)

Diagnoses that may mimic acute epiglottitis include laryngotracheobronchitis, croup or spasmodic croup, bacterial tracheobronchitis, a foreign body lodged in the larynx or vallecula, retropharyngeal or peritonsillar abscess, and hereditary or druginduced angioedema.

Diagnosis of viral laryngotracheobronchitis is usually made on clinical grounds. The typical child with croup is about 1-6 years of age, is in the midst of a URI, has stridor and cough, and is nontoxic in appearance. Under these circumstances, confirmation of the diagnosis can be made with neck radiographs (see

Figure 8-1

). Narrowing of the upper airway, commonly referred to as a steeple sign, is especially apparent on the anteroposterior (AP) radiograph. In epiglottitis, a lateral neck radiograph would show an enlarged epiglottis referred to as a thumb sign (

Figure 8-2

), if a radiograph were obtained (see answer 1).

For children with retropharyngeal or peritonsillar abscess there may be prominent swelling and erythema of the tonsillar bed or posterior pharyngeal wall, and inspection of the mouth can be diagnostic. The clinical presentation of diphtheria can also resemble epiglottitis. However, with the widespread use of DTaP vaccination, diphtheria is rare in the US. A child with maxillary sinusitis would present with facial pain, toothache, or headache. The physical examination would reveal the presence of pain on pressure applied to the area of the sinus. The patient who has purulent pansinusitis can appear toxic but does not have airway symptoms.

FIGURE 8-2.

Epiglottitis. Lateral soft-tissue x-ray of the neck demonstrating thickening of aryepiglottic folds and thumbprint sign of epiglottis. (Reproduced, with permission, from Knoop KJ, Stack LB, Storrow AS, et al. Atlas of Emergency Medicine, 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2010:437. Photo contributor: Richard M. Ruddy, MD

.

)

6.

(A)

The epidemiology of epiglottitis has changed. In the United States, this is no longer a disease of young children caused by

Haemophilu

s

influenzae

but rather a disease of teenagers and young adults. In these patients, the offending bacteriologic agent is usually

S aureus

.

Streptococcus pneumoniae

, betahemolytic streptococci, nontypeable

H influenzae,

and even fungi have occasionally been implicated. In teens and adults with symptoms of epiglottitis, it is important to verify human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status because opportunistic infections of the larynx are not uncommon in these patients.

7.

(A)

The primary cause of these deep neck infections is either

S aureus

or group A streptococcus. If there is concern for a diagnosis of deep neck abscess in a child, antimicrobial agents should be directed at these organisms. However, despite appropriate antibiotic therapy surgical drainage of a peritonsillar abscess is often necessary.

8.

(D)

Evaluation of spinal fluid in the toxic child with sinusitis is important before a course of antibiotic therapy is initiated because meningitis is not uncommon in this setting and will alter therapy. A CT scan may help localize any central nervous system (CNS) extension and is generally performed before the lumbar puncture.

9.

(C)

Epiglottitis is usually distinguishable from croup by the toxic appearance and the profound dysphagia seen in the child with epiglottitis. Patients with epiglottitis are 2-6 years old. Children with croup are 1-6 years of age and usually present amid an URI with prominent airway symptoms including stridor and a “barking” cough.

10.

(A)

Infectious croup (laryngotracheobronchitis) is most often caused by parainfluenza virus types 1 or 2. There is currently no vaccine for the parainfluenza virus, and croup remains common in the United States and all over the world. As in epiglottitis, croup affects young children. Initially patients with croup present with low-grade fever, rhinorrhea, stridor, and cough. If the disease progresses to airway obstruction, the child will have severe stridor and shortness of breath. With respiratory efforts, suprasternal retractions are also observed in children with severe croup.