Pediatric Examination and Board Review (247 page)

Read Pediatric Examination and Board Review Online

Authors: Robert Daum,Jason Canel

• Class I: minimal mesangial lupus nephritis

• Class II: mesangial proliferative lupus nephritis

• Class III: focal proliferative glomerulonephritis

• Class IV: diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis

• Class V: membranous nephritis

• Class VI: advanced sclerosing lupus nephritis

Patients with class I or II lesions generally respond well to CS, often low dose, or treatment only with hydroxychloroquine and continued observation of renal status. Class III is potentially a more significant lesion that may improve with CS treatment alone or with cytotoxic treatment, but it may also progress to a more severe renal lesion, such as class IV. Classes IV and V require aggressive medical management to decrease progression to renal insufficiency and failure. Class VI has marked glomerular sclerosis, suggesting an end-stage kidney. In addition to histologic classification, activity (inflammation) and chronicity (scarring) indexes are also assessed, which have a further impact on medical treatment decisions and renal prognosis. Lupus nephritis is associated with increased morbidity and decreased long-term survival. The poorer outcome is related to renal complications such as hypertension, nephrotic syndrome, and renal failure. Treatment of severe renal disease (cytotoxic drugs and high CS doses) may further contribute to morbidity and mortality. To help protect inflamed and compromised kidneys, blood pressure management is essential. Treatment with an angiotensin inhibitor is recommended. If progression to renal failure occurs, the patient undergoes dialysis until a transplant can be performed. A renal transplant is generally postponed until the patient’s SLE is quiescent. Fortunately, clinically significant lupus nephritis occurs in less than 5% of transplanted kidneys.

7.

(A)

The erythrocyte sedimentation rate and CRP are not helpful markers for SLE disease activity. Both are nonspecific studies affected by infection and other inflammatory conditions. The complement levels and anti-dsDNA titers reflect disease activity more reliably.

8.

(E)

The presence of APLA is associated with venous or arterial thrombosis, recurrent fetal loss, hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and livedo reticularis. Approximately half of patients with APLA do not have an underlying rheumatologic disease (primary APLA syndrome); the rest have secondary APLA syndrome, usually related to a rheumatic disease (especially SLE). It is important to test for the presence of APLA in any individual who presents with an unexplained venous or arterial thrombosis and also in patients diagnosed with SLE. APLA studies include lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin antibodies, and anti-beta

2

-glycoprotein.

9.

(C)

CS treatment is necessary to help control multisystem involvement in the vast majority of children with SLE. Unfortunately, prolonged use can lead to multiple complications. These include growth suppression (starting at doses equivalent to ≥3 mg/day in small children), musculoskeletal (osteoporosis, avascular necrosis, muscle wasting, myopathy), cardiovascular (hypertension, hyperlipidemia), ophthalmologic (cataracts, glaucoma), skin (striae, impaired healing), diabetes, secondary adrenocortical insufficiency, and immunosuppression. A major goal of medical therapy is to minimize the CS dose given. This, in part, is accomplished by using combination therapy. Hydroxychloroquine is often effective in treating skin, muscle, and joint involvement. It may also decrease the incidence of SLE exacerbations. Immunosuppressive therapy (including cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, cyclosporine A, and rituximab) is often given to patients whose disease is not controlled by CS or who have major organ system involvement, especially involving the renal and central nervous systems. Unfortunately, current treatment for SLE is not specific and usually involves global immunosuppressive therapy. Preventive measures employed in the management of SLE include treatment of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, osteoporosis, and administration of vaccines to decrease the risk of certain infections, especially pneumococcal or influenza.

10.

(C)

Although the prognosis for SLE has improved, most children with SLE are unable to discontinue all medications. Ten-year survival has increased from less than 50% in the 1950s to more than 90% currently. The most common cause of death is infection, followed by renal failure. Mortality occurring more than 10 years after SLE diagnosis is often secondary to cardiovascular complications such as myocardial infarction and stroke.

11.

(A)

Anti-Ro (SS-A) and/or anti-La (SS-B) antibodies are present in virtually all mothers who have babies with neonatal lupus erythematosus (NLE). These autoantibodies may be present in individuals with SLE, Sjögren syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and even in women with no rheumatologic symptoms or diagnosis. In women with SLE, only the presence or absence of anti-Ro and anti-La has an impact on the risk of having a baby with NLE, not the status of SLE disease activity. (However, women with active and severe SLE may be at increased risk of premature delivery, miscarriage, and other pre- and perinatal complications.) Clinical manifestations of NLE include rash, hepatitis, thrombocytopenia, and permanent congenital heart block (CHB). Except for CHB, the NLE manifestations resolve by 6 months of age, corresponding to the disappearance of maternal autoantibodies from the baby’s circulation. Some children may have residual scarring from skin lesions. Most children with CHB require pacemakers, many needing insertion during the first few weeks of life.

12.

(D)

Most patients with drug-induced lupus (DIL) have milder symptoms and less organ-system involvement than those with idiopathic SLE. The most common clinical manifestations in DIL are arthralgias/arthritis, myalgias, serositis, rash, and constitutional symptoms (such as fatigue and fever). Renal and neurologic involvement is rare. Antibodies to histones are often present; anti-dsDNA antibody is usually absent. Complement levels tend to be normal. The most commonly implicated drugs causing DIL in children include anticonvulsants (especially hydantoins and ethosuximide), isoniazid, and minocycline. Reported cases of DIL secondary to minocycline have increased greatly in the past decade, corresponding to its increased use in teenagers for the treatment of acne. In adults, hydralazine and procainamide are the most frequent triggers of DIL. Definitive treatment for DIL is discontinuation of the suspected triggering medication. NSAIDs are useful to treat fever, musculoskeletal involvement, and serositis. Although most patients do not require CS, some may require treatment for rare major organ system involvement or persistence of symptoms.

13.

(C)

Raynaud may occur in patients with rheumatologic disease (secondary Raynaud or Raynaud phenomenon) and in individuals without an underlying rheumatologic process (primary Raynaud or Raynaud disease). Primary Raynaud is most common in adult women, usually during their third and fourth decades of life. It may occur in teenage girls but is rare in prepubertal children and teenage boys. In both primary and secondary Raynaud, the triphasic color change, in order, is white → blue → red. The pathogenesis is arterial vasoconstriction with subsequent reduction in local blood flow, particularly to the hands, the toes, and occasionally the ears, nose tip, and lips. It is usually triggered by cold temperature or emotional stress. It is important to know if a child with Raynaud has a primary or secondary process. The history, physical examination, and laboratory evaluations are all essential to help determine this. The history may reveal multisystem complaints. The presence of pitting or scarring of the distal digital pulp, finger edema, sclerodactyly, or changes in the nail-fold vessels suggest a secondary Raynaud process, as does the presence of a high ANA titer. Raynaud’s phenomenon occurs in systemic sclerosis (>90% of patients), mixed connective tissue disease (about 50%), and SLE (about 35%). Treatment includes patient education to keep the extremities warm and the core temperature up, vasodilators (such as calcium channel blockers), and biofeedback.

14.

(A)

Dystrophic calcification, or calcinosis, is a late feature of juvenile dermatomyositis (JDM), usually developing months to years after the initial symptoms of rash and muscle weakness. Proximal muscle weakness, muscle tenderness, and active skin lesions, including diffuse cutaneous vasculitis and erythema over the extensor aspects of the elbows and knees may be present.

15.

(B)

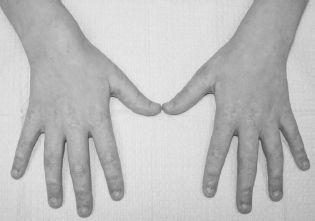

ANA and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate are nonspecific laboratory studies that do not help with the diagnosis of JDM. The diagnosis requires the presence of the classic rash consisting of Gottron papules that are scaly, erythematous lesions over the dorsal aspects of the metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal joints (

Figure 141-2

), and a heliotrope discoloration over the upper eyelids, often with mild periorbital edema. The presence of at least 2 of the 4 following criteria is also needed to make the diagnosis: (1) symmetric proximal muscle weakness, (2) increase in the serum of one or more skeletal muscle enzymes (creatine kinase, aldolase, aspartate aminotransferase, lactic dehydrogenase), (3) electromyography (EMG) demonstrating myopathy and denervation, and (4) a muscle biopsy showing inflammation and necrosis. If the first 2 criteria are present, the invasive studies, specifically EMG and muscle biopsy, are rarely needed. A noninfused MRI of the gluteal and thigh muscles may show areas of edema, consistent with muscle inflammation. This tool is being employed more commonly to help in the diagnosis of JDM. It may be difficult to evaluate the presence of muscle weakness in a child younger than 7 years of age in whom it is often not possible to perform formal muscle strength grading. Therefore, assessment of gross motor skills (such as the ability to squat and arise, balance, jump, hop, get on and off the floor, and ascend stairs) is an essential part of the physical examination. Look for a positive Gower sign (the use of the arms to assist in transitioning from a kneeling or prone position to standing, by “walking” the hands up the thighs).

FIGURE 141-2.

Erythematous, scaly lesions (Gottron’s papules) over the dorsal aspects of the metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal joints in a 10-year-old girl with dermatomyositis. Nailfold telangiectasias can also be seen. See color plates.

16.

(D)

In JDM, weakness of the skeletal muscles employed in swallowing (proximal esophageal, palatal, pharyngeal, and hypopharyngeal muscles) may lead to dysphagia, regurgitation of liquids through the nose, and dysphonia with nasal speech. The risk of aspiration is quite real in these patients who require aggressive medical management and may need protection of the airway. Overall, the prognosis of JDM has improved greatly since the availability of CS, which is the first line of treatment. In the pre-steroid era, at least a third of patients died (usually secondary to respiratory failure or GI vasculitis), and another third had major morbidity (significant residual weakness and/or severe calcinosis). Currently, CS treatment is given to all JDM patients, with duration of therapy lasting more than 1 year, often 18-24 months, depending on the clinical response. A rapid taper of CS or total treatment duration less than 6 months is often associated with disease exacerbation. Some JDM patients require additional medications. Methotrexate is the most commonly used second-line agent. Cyclosporin and IVIG also have demonstrated efficacy. JDM treatment with biologics is being evaluated. Currently, long-term survival is more than 95%, and more than two-thirds of patients have good to excellent outcomes. Calcinosis is still a major cause of morbidity and reflects prolonged periods of poorly controlled disease (

Figure 141-3

). Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment of JDM are essential because they have been shown to decrease mortality and morbidity.