Pediatric Primary Care Case Studies (81 page)

Read Pediatric Primary Care Case Studies Online

Authors: Catherine E. Burns,Beth Richardson,Cpnp Rn Dns Beth Richardson,Margaret Brady

Tags: #Medical, #Health Care Delivery, #Nursing, #Pediatric & Neonatal, #Pediatrics

3. Integrate knowledge of development, pharmacology, and complementary approaches to develop a treatment plan for the young child with primary headache.

Case Presentation and Discussion

John Brown is a 6-year-old who presents to a private practice with a complaint of headache. He has been having headaches for about 3 months and has seen two other providers without any relief. The child is accompanied by his father. The father explains that he is the primary parent since his 42-year-old wife died of lymphoma 3 years ago. He expresses concern that the child has missed 6 days of school over the past 3 months due to headaches and would like your opinion on the problem.

What questions will you ask John and his father about the “headache” problem?

Your symptom analysis reveals the following information: The child started with a headache 3 months ago and has been getting between two and three headaches per month. They are described as 5 of 6 on the Wong Pain Scale and are throbbing and bilateral over the top of the head or the forehead, lasting 5–8 hours. The headaches do not have any specific time that they commence; however, they do not wake the child up at night, and he has not had them in the morning. John generally feels nauseated with the headache but has vomited only once. During the headache episode, the child looks like he is sick. The father has not identified any precipitating factors or triggers. He reports that John’s mother had migraines that would last for 2 days, and he does not want John

to be as debilitated as his mother was. The headaches are not related to activity. He has been given acetaminophen (Tylenol) for the headaches by the other two providers without much relief. The father was not happy with the care of the other providers because they rushed through the exam and “made light” of his concerns.

What other questions do you need to ask John and his father?

Before answering this question, here is some information about headaches that you need to consider.

Headaches in Children

Headache is a common pediatric disorder that has become more common in adolescents (Lewis, 2007c). Overall, prevalence is between 37% and 51% in 7 year olds with an increase to as high as 82% in 15 year olds (Lewis, 2007a).

Pathophysiology of Migraine

The pathophysiology of migraine is not fully understood, but is now believed to be a neuronal process (Lewis, 2007b). The current thinking is that the cerebral cortex is hyperexcitable, with genetic influences causing disturbances in the neuronal ion channels (Lewis, 2007b; Lisi et al., 2005). This leads to a lowered threshold for a variety of external and internal factors to trigger episodes of excitation of the neuronal region. Subsequent to this, there is a cortical spreading depression that is likely responsible for the aura seen in migraine and for the activation of the trigeminovascular system (Lewis, 2007b). During the aura phase of migraine, there is regional neuronal depolarization as well as a decrease in blood supply or oligemia.

Because an aura is present in only about 30% of children, there are two mechanisms of pain generation (Lewis, 2007b). The first reason for pain is from the inflammation of the meningeal vessels, and the second reason is the sensitization of peripheral and trigeminal afferents (Lewis, 2007b). Some of the substances involved in the generation of the inflammation and sensitization of the vasculature in the brain include neurokinine, substance P, and calcitonin gene reactive peptide, which cause dilatation with subsequent pain. The vasoreactive neuropeptides act on blood vessels. Serotonin and glutamate may increase the sensitivity to pain in the blood vessel wall (Gunner, Smith, & Ferguson, 2008).

Migraine is now divided into three major subclassifications—migraine with aura, migraine without aura, and childhood periodic syndromes that are commonly precursors of migraine (Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society [IHS], 2004). In children, a migraine headache must last between 1 and 72 hours with moderate to severe intensity, with aggravation by usual physical activities, and with behavioral signs of either photophobia or phonophobia (IHS, 2004). The diagnostic criteria for pediatric migraine without aura are not based on one attack. The patient must have five attacks that include the following criteria: 1) headache attacks last between 1 and 72 hours; 2) headaches minimally need two of the four characteristics—

unilateral or bilateral, frontotemporal but not occipital location; pulsing quality; moderate to severe pain; and physical activity limitations resulting from the headache; 3) headaches should have one of the following symptoms—nausea and/or vomiting, photophobia, or photophobia inferred from their behavior; and 4) cannot be attributed to another disease (IHS).

In migraine without aura, there may be autonomic symptoms such as nausea, anorexia, periumbical abdominal pain, diarrhea, pallor, photodysphoria, photophobia, a desire to sleep, cool extremities, goose flesh, increased or decreased blood pressure, or periorbital discoloration (Lewis, 2007b). In migraine with aura, the most common visual phenomena are binocular visual impairment with scotoma, with distortions or hallucinations, or monocular visual impairment occurring much less frequently (Lewis, 2007b).

Pathophysiology of Tension-Type Headache

Tension-type headaches (TTHs) are the most common type of headache and are now felt to have a neurobiological basis (IHS, 2004). Central pain mechanisms are felt to play a role in frequent tension headaches, whereas peripheral pain mechanisms play a role in infrequent episodic tension headaches (IHS). A TTH is described as a symmetrically distributed tightening “band-like” feeling around the head (Rubin, Suecoff, & Knupp, 2006). There may be associated photophobia or phonophobia, but without nausea, vomiting, or exacerbation with activity (IHS). The diagnostic criteria for tension-type headaches require at least 10 episodes of headache. The headaches must fulfill the following criteria: 1) last between 30 minutes and 7 days; and 2) need two of the four characteristics—bilateral location, pressing/tightening of a nonpulsating quality, mild to moderate intensity, and not be increased with routine activity such as walking or climbing stairs. In addition, there can be no associated nausea, vomiting, photophobia, and phonophobia. The headache cannot be the result of another disease process (IHS).

There are three subtypes of TTHs: infrequent episodic TTHs with headaches occurring less than 1 day a month, frequent episodic TTHs with headache episodes occurring 1 to 14 days a month, or chronic TTHs with headaches 15 or more days a month. In children, it may be difficult to distinguish between migraine and tension due to the developmental level of the child (Brna & Dooley, 2006).

Pathophysiology of Cluster Headache and Other Trigeminal Autonomic Cephalalgias

It is hypothesized that ipsilateral trigeminal nocioceptive pathways are important in the etiology with the activation of the parasympathetic cranial system and ipsilateral parasympathetic nerves. An inflammation of the cavernous sinus and tributary veins is believed to be the main mechanism involved in cluster headaches (Lampl, 2002). A cluster headache is a unilateral burning pain that is most commonly found around the eye and orbits on the affected side, occurring from one to eight times during the course of the day (Lampl).

Epidemiology of Headaches

Migraine headaches can start at age 6 to 7 years and once puberty occurs, the female to male ratio is 2:1 (Lewis, 2007a). The headache is usually bilateral in children and usually frontotemporal, with occipital headaches being rare and needing immediate evaluation for structural lesions (IHS, 2004). Migraine with aura peaks at 5 to 6 years of age in boys and between ages 12 and 13 years in girls (Lewis, 2007a). Migraine prevalence estimates vary from 1–3% at 7 years of age with an increase to as high as 11% in the later school-age child and mid-adolescent (Brna & Dooly, 2006).

Cluster headaches are rare in the pediatric age group, with prevalence of 0.09% to 0.4% for male patients. From age 11–18, the prevalence of childhoodonset cluster headaches is 0.1% (Lampl, 2002).

Tension headache is more common in older girls. General prevalence is between 30% and 78% in the general population.

Social Factors

Mr. Brown is a single parent and has a full-time job. When questioned about his ethnicity, he denies belonging to any cultural group and feels he is a mixture of races. So in this case, it is important for you to explore what he believes about health care, medications, and complementary medications. Because the father has expressed concern about the management plan that was identified during prior healthcare visits related to John’s headaches, you need to spend time explaining the diagnosis and evaluating Mr. Brown’s acceptance of and desire to be involved in deciding on the management plan. Using the skills of motivational interviewing can be helpful in exploring parental expectations of the healthcare visit.

Further Assessment Data Required for the Differential Diagnosis?

The differential diagnosis is vast but needs to be approached systematically by first deciding whether the headache is a primary problem or a secondary symptom to another problem. A complete history and physical examination are the first steps in making the decision.

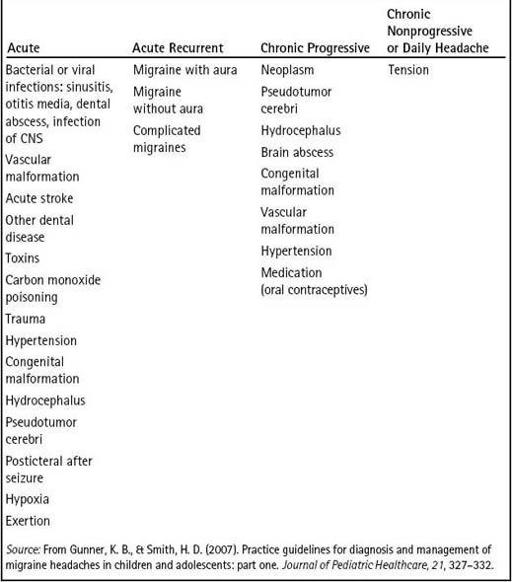

Table 20-1

reviews possible differential diagnoses for headaches in children. The key to confirming the diagnosis is compliance with the treatment plan and good follow-up with the family.

From the above review, what additional questions should you ask?

History

• When did the headaches begin? If the problem has been going on for years, make sure there are no recent changes in the headache presentation.

• How often are the headaches, and has there been a change in frequency? What is the interval between the headaches? Migraines are not daily whereas TTHs can be daily or several times a week. Cluster headaches occur in clusters of two to three per week over a few weeks and then do not occur for a period of time (Brna & Dooley, 2006).

Table 20–1 Differential Diagnoses for Headache