Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront (5 page)

Read Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront Online

Authors: Harry Kyriakodis

Four treads of the Wood Street Steps have cracked in half and are sagging as a result of subsidence. River's Edge Civic Association is planning to repair the steps and conduct an archaeological investigation beneath them. The group also wants to draw attention to this and all the Penn stairwells via the installation of a Pennsylvania State Historical Marker.

S

HIPBUILDING

(I

OF

III): T

HE

W

EST

S

HIPYARD

/H

ERTZ

L

OT

Wood Street got its name from timber being carted along it to a handful of eighteenth-century shipyards fronting the Delaware River in the vicinity of Vine Street. Indeed, under the parking lots approximately in front of the Wood Street Steps are the remains of the West Shipyard, one of four local yards fabricating fishing craft, riverboats and oceangoing vessels.

James West (?â1701) set up his yard on the west bank of the river as early as 1676, years before the arrival of William Penn in America. In the days before dry docks, sailing ships needing repair would be dragged up slipways (launching ramps) to enable repairs to be made. New vessels, needless to say, were also built on such ramps. A ropeyard was immediately north of the West Shipyard.

After West's death in 1701, his son took over and developed the shipyard into a miniature “company town,” complete with shops and inns to support its workers. But the yard became less useful as ships became both larger and equipped with steam engines driving propellers and paddle wheelsâhauling ships ashore was no longer practical. The West Shipyard had faded from the scene by the early 1800s, and the old slipways and quays were filled in (again, made-earth) as Philadelphia's waterfront was pressed farther east into the Delaware.

Disturbances at this site were relatively minor because the structures built thereâa coal yard, a fruit warehouse, the Vine Street Market, etc.âdid not have deep foundations. By the early 1900s, a rail yard of the Reading Railroad covered the block. Now topped by a parking lot across from Pier 19, the West Shipyard may be the last intact vestige of Philadelphia's colonial port heritage.

A small archaeological dig was carried out in 1987 at part of the plot encompassing the West site. (The ground is identified as the Hertz Lot from the car rental firm previously in business there.) Among the findings were the remnants of eighteenth-century wharves and a slipway, all in good condition. The dig was filled and paved over afterward to keep it preserved. This was the first archaeological site on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places.

The Hertz Lot slipway is the only feature of its kind unearthed in excavations on the East Coast. Since the West Shipyard escaped the havoc wrought by Interstate 95, there is undoubtedly much valuable material buried not far underground. A dig here may yield a fine record of the parcel's uses from 1676 until recent times. Plans for such an excavation are in the works.

P

ENNY

P

OT

T

AVERN AND

L

ANDING

The bowsprits of ships at West's yard almost reached the eaves of buildings on Water Street. One of these was the Penny Pot Tavern. West bought this well-known landmark from a widow in 1689 or 1690. As specified by Watson, it was situated three houses north of the northwest corner of Vine and Water. The tavern was a two-story brick structure with its front facing south.

The renowned Penny Pot Tavern was allowed to sell beer for “a penny a pot” (or quart), as per the Duke of York's decree in 1682. It was therefore a place where beer could be bought for about half the price of most other brew houses.

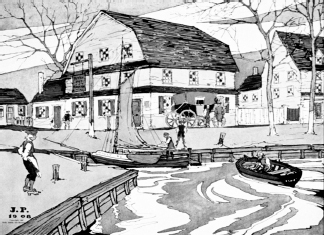

The Penny Pot Tavern and its adjacent landing at Vine Street.

Library of Congress

.

The saloon became the Jolly Tar Inn after 1800 and was later incorporated into the Rising Sun Hotel next door. The Penny Pot building burned in a fire that destroyed the entire block in 1850 (discussed later). The edifice currently on the site contains a quarter-sized facsimile of the tavern on the roof. Best seen from Front Street, it was erected by the architect who moved there in the 1970s.

The Penny Pot Landing, built by James West, was basically in front of the inn, between his shipyard and the Vine Street Landing. The two ultimately became one and the same.

V

INE

S

TREET

L

ANDING AND

F

ERRY

Vine Street was originally called Valley Street since a ravine or vale led to the Delaware River there. This is why a boat landing was to be found at this point even before William Penn's era; the valley offered easy access into the region's interior. Hunters and traders from settled territories in New Jersey had crossed the channel there throughout the 1600s to get to the bountiful lands of what became Pennsylvania.

Penn had first dedicated the Vine Street Landing for public use in 1683. He further proclaimed in his “Charter of Privileges” for inhabitants of Pennsylvania (1701) that “the Landing-places now and heretofore used at the Penny-pot-house and Blue-anchorâ¦shall be left open and common for the Use and Service of the said City and all others.” Penn wanted to prevent some enterprising Philadelphian from buying the rights to these boat landings, which he intended for public use indefinitely.

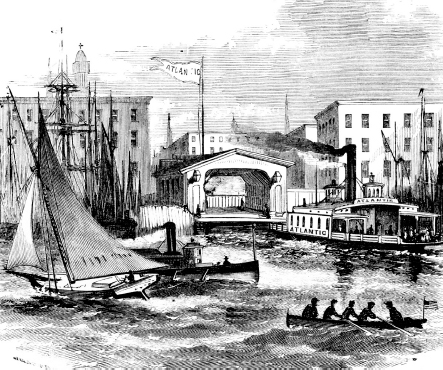

The Vine Street Landing was one of the busiest ferry landings on the Delaware. In the early 1700s, it primarily serviced the Upper Ferry (otherwise known as “Uncle Billy's Ferry”) operated by William Cooper. The Cooper's Point Ferry, a more formal venture, took over this route and later became associated with the Camden and Atlantic Railroad. Eventually taken over by the Pennsylvania Railroad, that rail line ran trains to Atlantic City and other shore resorts.

Cooper's Point Ferry billed itself as “Philadelphia's Front Door to Atlantic City.” Countless Philadelphians boarded ferryboats at Pier 16 North to get to the line's Camden (New Jersey) terminal, where they would board trains that would take them to the seaside for a few days of relaxation.

An 1875 view of the Vine Street Landing and Ferry.

Adam Levine Collection

.

When it went out of business in 1926 or so, the Vine Street Ferry was reputed to be the oldest ferry service in America, operating continuously for more than two hundred years.

F

ERRIES

C

ROSSING THE

D

ELAWARE

(I

OF

II)

The Vine Street Landing was not unique. A public boat/ferry landing was at the base of every eastâwest street in Philadelphia's younger years. The ferries allowed people to cross the Delaware in the days before the Benjamin Franklin Bridge provided the first Philadelphia crossing. They transported travelers, shoppers and day-trippers from Philadelphia and Camden and from points all over. Some boats were powered by horses driving a paddle wheelâhorse-boats. Oarsmen propelled others.

Then came the Industrial Revolution. The factories, shops, stores and offices of both Philadelphia and Camden employed hundreds of thousands of workers, and some of them lived or worked on the opposite side of the river. So they had to take a ferry trip twice daily. To meet the demand, steam-powered ferries plied the Delaware by the middle of the 1800s.

S

HIPBUILDING

(II

OF

III): O

VERSEAS

T

RADE AND THE

A

MERICAN

C

LYDE

Other boatsâfirst sailing ships and then steamshipsâwould take people to Bristol, Burlington, Trenton, Chester, Wilmington, Baltimore and so forth. Ships sailing to England, the West Indies, China, India and other remote destinations routinely left from the city's Delaware waterfront in the 1700s and 1800s. Philadelphia merchants were known in the “counting houses” of the far corners of the world from the 1790s to the 1850s.

A group of Philadelphia and New York merchants had equipped the first American ship to sail to China. The

Empress of China

left New York City on February 22, 1784, and landed in Canton that August 28. The ship returned in 1785 with a full load of silks, porcelain, spices and tea, thus starting the American-China trade.

Also in 1784, the first American ship to visit India departed Philadelphia on March 24. The

United States

was outfitted by a group of Philadelphian merchants and reached the city of Pondicherry later in 1784. Eight years later, the brigantine

Philadelphia

was the first American ship to visit Australiaâas well as perhaps the first foreign trade vessel ever to visit Australia. Plus, the frigate

John

left Philadelphia to become the first American ship to visit South America, arriving at the present capital of Uruguay in 1798.

Many of these vessels were made in shipyards up and down the Delaware River. The Delaware was even nicknamed the “American Clyde” because it rivaled Europe's great shipbuilding region on Scotland's Clyde River. Ship fabrication firms included Neafie & Levy, John Roach & Sons, Simpson & Neill, Bireley, Hillman & Co. and William Cramp & Sons. James West's yard was part of the progression of this industry, as was that of Joshua Humphreys, discussed in

chapter sixteen

.

Philadelphia's shipyards became vast operations as ships transitioned from sail to steam power and from wooden to iron hulls. Local shipyards set records for physical plant and production during the heyday of American shipbuilding around World War I. Hundreds of thousands of workers were employed in building ships and in related maritime industries on both banks of the Delaware. This concentration of shipyards was the largest shipbuilding industry in the world.

Alas, the building and repairing of ships is no longer a major industry in Philadelphia. The last machine shop of Cramp Shipyardâone of several structures of a thirty-acre compound in the city's Kensington districtâwas demolished in early 2011. Why? To build a new I-95 interchange, but of course.

T

HE

F

ROZEN

D

ELAWARE

From the Vine Street Landing and other places that offered easy access to the Delaware, people would skate on the iced-over river during the many times it froze in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Skating early on became a sport in which Philadelphians were noted, possibly because Quaker leaders approved of this ostensibly frivolous pursuit.

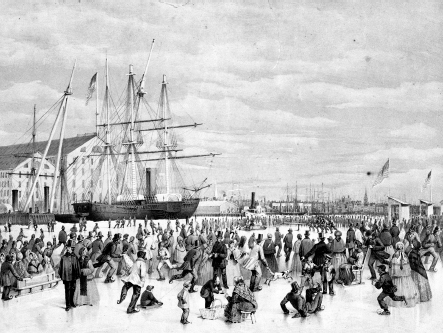

Ice-skating on the frozen Delaware in the winter of 1856, near the first Philadelphia Naval Yard. This is an image of one of several instances of such a scene in the 1800s.

Library of Congress

.

Watson describes the scene vividly. On days the Delaware was frozen, booths were put up to sell refreshments to the gathered crowd; sometimes an ox roast would add to the excitement. Horses were also specially shod for racing sleighs on the solid river, and the course would go miles upstream. The ice could get so thickâoften more than two feetâthat horses pulled loaded ferryboats across the channel atop the ice!

It's no wonder that the first steam-powered icebreaker in the world was built for Philadelphia in 1837 to keep traffic moving on the Delaware during winter months. Christened

City Ice Boat No. 1

, this was the first of a local fleet of such ships. Its original steam engine was made by Philadelphia's Matthias Baldwin, who later won fame for his railroad locomotives.

City Boat 1

cost $70,000 to build and remained in service for eighty years.