Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront (8 page)

Read Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront Online

Authors: Harry Kyriakodis

Its name was changed to the Benjamin Franklin Bridge in 1956 to mark the 250

th

anniversary of Franklin's birth and to distinguish it from the newly constructed Walt Whitman Bridge. The Delaware River Port Authority manages these and other spans over the Delaware, in addition to the PATCO High-Speed commuter rail line, which uses the Ben Franklin Bridge to provide service into Center City (downtown) Philadelphia.

At the water's edge was Pier 12 North, operated by the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad for general freight purposes and where the railroad docked its floating barges. Pier 12 today is home to the Philadelphia Marine Center. This is Philadelphia's leading boating facility, offering 338 deep-water slips.

The Pennsylvania Railroad used Piers 13 and 15 North as a city freight station, shipping 1,800,000 tons annually of general merchandise carried in railroad cars on car floats. About four hundred men worked at these wharves, which are no longer around. Octo Waterfront Grille is at Pier 15 today.

T

HE

S

UMMER

S

TREET

S

TEPS

The bank stairway between Vine and Race was at Summer Street, an intermittent lane that once crossed the city. This tiny street was also one of the alleys that cut through the made-earth between Water Street and Delaware Avenue. It's still there today, providing access to both North Water Street and I-95 North from Delaware Avenue.

The Summer Street Steps lasted until 1925, when the Delaware River Bridge's Philadelphia Anchorage was completed. The stairwell was removed as part of grading and paving around the gargantuan structure. A work contract drawing showing existing conditions labels a set of “Stone Steps Down” on the line of Summer Street between Front and Water. Another drawing shows that the steps were replaced with a concrete sidewalk. That sidewalk must have lasted until the 1970s, when Interstate 95 came through.

The Philadelphia Anchorage extends from Columbus Boulevard to Front Street. Its foundations required twenty-eight thousand cubic yards of concrete and go down sixty-three feet to bedrock. The excavation yielded some surprises. The following is from the final engineering report for the bridge, issued in 1927:

It was known that old bulkhead walls existed between Delaware Avenue and Water Street at the site of the Philadelphia anchorage. Test pits excavated before the buildings were demolished disclosed considerable timber cribbing of this nature. Some of it had evidently served as foundations for earlier buildings, but most of it was probably wharf construction along the water front of Colonial days. Since buried timbers of any considerable size would offer a serious obstacle to dredging operations, the specifications provided that the site should be prepared by stripping so much of the overlying fill as found necessary to remove all old foundations and buried timbers. During these operations, hewn oak timbers 24 inches square and parts of a barge or boat framed with wooden pins were removed

.

Many commercial buildings were cleared to build the Philadelphia Anchorage in the early 1920s, and half of Water Street was eliminated between Race and Vine. What's more, the imposing structure's sudden appearance surely hastened the waterfront's decline. Besides interrupting Water Street, the Delaware River Bridge visibly transported people and vehicles high above and away from that part of town. The obvious psychological effect was that the riverside commercial district was unworthy.

Construction of Interstate 95 had an even more devastating physical and psychological effect five decades later.

8

R

ACE TO

A

RCH

F

IGHTING

F

IRES AND

R

ATS

N

EAR

A

MERICA

'

S

O

LDEST

U

RBAN

S

TREET

Race Street was originally called Songhurst Street after John Songhurst, a friend of William Penn and an original Quaker settler of Philadelphia. Its name then became Sassafras Street.

The street's current name came about because this was the main roadway heading to horse races that occurred at or around Center Square (where Philadelphia City Hall is today) and because of occasional horse races on the street dating back to the 1720s. The designation continued long after the racing ended.

R

ACE

S

TREET

C

ONNECTOR AND

C

IVIC

P

LANS FOR

P

HILADELPHIA

'

S

W

ATERFRONT

Race Street east of Second Street was shifted roughly thirty feet north during Interstate 95's construction. The altered street winds its way under the highway overpassâan unappealing tunnel for pedestrians to use in accessing the Delaware River from Center City.

To meet the long-standing need to enhance this streetscape, the Race Street Connector project of 2011 added wider sidewalks and landscaping. Plus, an LED light screen attached to the viaduct's underside displays abstract images of the river in real time, to remind pedestrians that a river lies ahead. In announcing funding from the William Penn Foundation for these improvements, Mayor Michael Nutter declared in early 2011: “We will have one of the best waterfronts in America.”

The Race Street Connector is a project of the Delaware River Waterfront Corporation (DRWC). A successor to the Penn's Landing Corporation, this nonprofit corporation acts as the steward of the riverfront so as to provide a benefit to inhabitants and visitors of Philadelphia. DRWC intends to transform the seven-mile sweep of the city's river frontage between Allegheny and Oregon Avenues into a destination location for recreational, cultural and commercial activities. Race Street is the first of about a dozen streets slated to be improved with easier access to the Delaware.

R

ACE

S

TREET

P

IER AND

P

IER

9 N

ORTH

The Race Street Connector will definitely provide and promote access to Race Street Pier. This once-abandoned municipal pier was turned into a verdant riverside park in early 2011. Its upper level provides a sky promenade and almost forty white swamp oak trees, while a lower terrace offers seating for social activity and passive recreation. This new park on the water was the first significant public space designed and built by the DRWC. On May 12, 2011, Mayor Nutter presided over the official ceremony that placed the pier, once again, into public service. Project cost: at least $7 million.

Race Street Pier was looking shabby by 1931, just before it was rebuilt and lost its recreational pavilion.

Philadelphia City Archives

.

The city constructed the pier about 1900 at a cost of $409,532. The north side was used as berths for fireboats and harbor police craft while the south side was leased for freight service, mostly tropical fruits of the United Fruit Company. At 540 feet long, Race Street Pier could accommodate most cargo ships and passenger liners of that day. It was first labeled Pier 10 and was renamed Pier 11 after being rebuilt in 1931.

The modern use of this renovated pier relates back to when it had a pavilion (with four turrets) on its upper level, covered but open at the sides. There, people would enjoy themselves by strolling and breathing fresh river air over the Delaware. Firemen would dry their fire hoses inside the turret towers. The pavilion was dismantled during the 1931 rebuild. The warehouse structure was subsequently taken off the substructure, and the pier sat flat and forlorn for decades.

South of Race Street Pier is Pier 9 North, a concrete and steel structure (with a monitor roof) that was completed in 1919 for $867,000. Banana boats used to unload their cargoes at this city-owned pier. It was common to see long lines of wagons on Delaware Avenue waiting their turn to drive into this warehouse to load bananas destined for market stalls throughout Philadelphia. Despite looking old and tired, Pier 9 is sound and is used for storage. It may ultimately become a performance or exhibition venue.

C

ONTAGION BY THE

D

ELAWARE

(I

OF

II): T

HE

P

HILADELPHIA

R

AT

R

ECEIVING

S

TATION

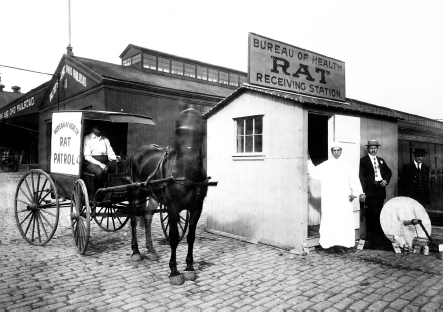

The front of Race Street Pier was a place to be avoided a century ago, for the Rat Receiving Station of the Philadelphia Bureau of Health was located there. Rats were a big problem all along the Delaware, and city officials sought ways to get rid of them and the diseases they carried (bubonic plague in particular).

At least six special agents maintained scores of rat traps along the river from Girard Avenue to Reed Street. They also rat-proofed buildings on the riverfront and inspected ships docking along the Delaware. Horse-drawn wagons marked R

AT

P

ATROL

aided their efforts and emphasized their authority. More than anything, the agents enforced a rule mandating that all vessels from rat-infested ports had to have rat guards on their mooring lines.

The Philadelphia Rat Receiving Station in front of Race Street Pier, along with a R

AT

P

ATROL

wagon, 1914.

Philadelphia City Archives

.

Moreover, citizens were encouraged to bring rats to the station for a bounty: five cents for live ones and two cents for dead ones. The station was established in 1914 and collected over five thousand rats by year's end.

T

HE

H

IGH

P

RESSURE

F

IRE

S

ERVICE

B

UILDING

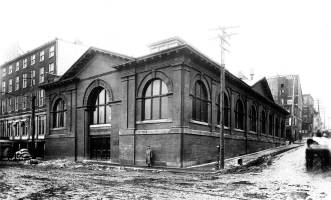

The High Pressure Fire Service (HPFS) building directly across Race Street Pier is one of the most important yet unappreciated edifices in Philadelphia. This red brick Victorian structure served the city for one hundred years, providing high-pressure water, at a moment's notice, for use in fighting fires. Along with the high-pressure pipeline system that distributed the water, this building is the main reason why Center City Philadelphia never suffered a catastrophic fire during the 1900s.

Philadelphia's regular-pressure water had become ineffective in fighting fires in increasingly larger and higher buildings in the central business district. Years of prodding by insurance companies and the Philadelphia Fire Department spurred the city to install the world's first high-pressure water service in a major city. Inaugurated in 1901 and completed in 1903, the system delivered water via independent pipes and special red fire hydrants located on every block between the Delaware River and Broad Street, from Race to Walnut.

The High Pressure Fire Service building in 1904, just after completion. It looks much the same today, though a little worse for wear.

Philadelphia City Archives

.

The HPFS building on Delaware Avenue drew water right from the river via a twenty-inch main and supplied a network of twelve- and sixteen-inch mains. Seven 280-horsepower pumps were powered by engines operating on city gasâan early use of internal combustion engines for such work. Full pressure was available within two minutes from the time a fire alarm was sounded.