Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront (9 page)

Read Philadelphia's Lost Waterfront Online

Authors: Harry Kyriakodis

The system had the capacity of pushing ten thousand gallons of water a minute at up to three hundred pounds of pressure, with power to throw a two-inch stream 230 feet vertically. Fireboats on the Delaware were also used for backup. They connected to the system via a manifold that still protrudes from the sidewalk in front of Race Street Pier.

Fire losses immediately dropped after the HPFS system was operational, prompting the removal of extra insurance charges imposed on structures within the congested downtown. Other pumping stations followed around the city when the system was expanded into surrounding neighborhoods. The system's success brought about similar high-pressure water systems in other American cities. Philadelphia's was acknowledged as the best in the world for years and years.

The fifty-six-mile system lasted until 2005, when it was decommissioned after falling into disrepair. High-pressure water service had become unnecessary anyway due to better firefighting equipment, high-rise sprinklers and fire-resistant construction materials. The HPFS building, though, still heroically stands. It is scheduled to become office and performance space for the Philadelphia Live Arts Festival (Philly Fringe). A café is also part of the scheme.

The Salt Fish Store was built in 1705 where the HPFS building is today. This undated photo shows the steepness of Race Street as it approached Delaware Avenue. Two policemen are keeping the peace.

Philadelphia City Archives

.

The old pumping plant sits where a salt house was situated for roughly two hundred years. This was a place to store and sell salt and salt fish. Built in 1705 with bricks and timbers imported from England, it was one of the first structures erected on this stretch of the Delaware. Other enterprises used the storehouse before it was taken down about 1903.

T

HE

C

HERRY

S

TREET

S

TEPS

The ten-foot-wide passageway between Race and Arch wasâand still isâcalled Cherry Street, and the bank steps thereon were known as the Cherry Street Steps. William Penn may have directed his surveyor, Thomas Holme (1624â1695), to plan for this specific set of riverbank steps when Philadelphia was platted. (It was Holme who designed Philadelphia as a grid between the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers.)

Since the Cherry Street Steps were adjacent to property that Holme owned on Front Street, he or his heirs may have installed the stairwell. There's evidence of this in Irma Corcoran's book

Thomas Holme, 1624â1695

(1992):

Thomas Holme was to leave a cartway thirty feet along the bankâ¦Moreover, he was to lay out his proportion and part so that in the center between Mulberry and Sassafras Streets a public thoroughfare ten feet wide could be made down from the east side of Delaware Front Street

.

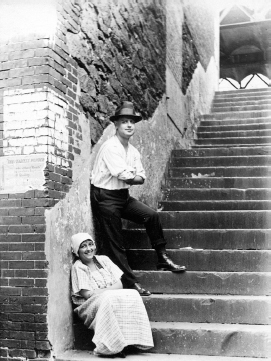

The Cherry Street Steps are the most documented of any of the lost Penn steps, at least in terms of illustrations and photographs. The staircase was drawn many times by Philadelphia artist Joseph Pennel. And a charming photograph taken by G. Mark Wilson shows a man and a woman in the stairwell. According to

Still Philadelphia

(1983):

Wilson's quest for picturesque Philadelphia led him to quaint scenes, some superficially evocative of Europe. He captioned this early 1920s photograph “not in Florence, Genoa or Naples,” but the facts he supplied with the image make it clear that the scene was uniquely American. The couple seemed to be courting. The man, Wilson noted, was Jewish, the woman Irish, a circumstance almost unimaginable where Old-World customs and proscriptions still held sway

.

The Cherry Street Steps about 1920. Notice the Frankford El structure atop Front Street in the background.

The Library Company of Philadelphia

.

Undeniably, this was an immigrant community in the 1920s.

These bank steps were obliterated for sure when I-95 barreled through Philadelphia in the late 1960s.

E

LFRETH

'

S

A

LLEY

John Watson, in his

Annals

, refers to the Cherry Street Steps as the Elfreth's Alley Steps. This is because they were a bit south of Elfreth's Alley, now a popular tourist attraction between Front and Second Streets. This National Historic Landmark District is the oldest continuously occupied residential street in the United States.

Elfreth's Alley was opened in 1702 by John Gilbert and Arthur Wells, two property owners who combined their land to create a subdivision through the city block they owned. The alleyway's namesake was Jeremiah Elfreth, a blacksmith who rented several houses on the block to sea captains, stevedores, shipwrights and craftsmen, some who worked in the same buildings where they resided. It has been the home to all sorts of people in its more than three hundred years, from wealthy friends of Benjamin Franklin to immigrant families.

Looking east on Elfreth's Alley in 1972. Most Philadelphia alleys by the Delaware resembled this scene long ago. Many are still around. Elfreth's Alley is the best known and looks even better today.

Library of Congress (HABS)

.

During the Industrial Revolution, the alley became an enclave for European immigrants seeking new lives in North America. As such, they were not all that different than the Quaker settlers who lived in caves by the Delaware River. The tiny row homes on Elfreth's Alley are excellent examples of Philadelphia's Colonial, Georgian and Federal housing of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Most are private dwellings to this day.

The alley had become an impoverished neighborhood by World War I and faced possible demolition. In 1934, a group of individuals formed the Elfreth's Alley Association to save several houses from being torn down by absentee landlords. They later helped rescue the alley from other threats, including construction of I-95.

Fireman's Hall Museum is on Second Street next to the alley, housed in a 1902 firehouse. This is one of the nation's premier museums on firefighting, many advances of which were developed in Philadelphia.

The Bank Meeting House was once on the riverbank south of Elfreth's Alley. Built in 1685, this early Quaker house of worship was used for 104 years before it was pulled down. The relocated Front Street between Race and Arch runs through ground on which this brick structure stood.

S

LEDDING

T

OWARD THE

R

IVER

âN

O

M

ORE

Watson wrote that “[t]hirty to forty boys and sleds could be seen running down each of the streets descending from Front street to the river” in his youth. The streets had been graded by his time to better join the “upper” and “lower” planes of Penn's City. Watson's sledding comment illustrates how the embankment's natural grade between Arch and Market Streets was where the change in height was the most pronounced.

There's definitely no sledding on these streets nowadays, chiefly because Interstate 95 truncated many of the eastâwest streets on the Delaware's edge. Arch was one of these streetsâblocked off with a solid brick wall that runs along the east side of Front. There was no way to avoid this since the superhighway changes from a below-grade to an elevated structure between Race and Market. The brusque disconnect of Arch Street from the waterfront of which it was such an integral part is truly regrettable. The same goes for Vine Street.

Other key eastâwest streets cut short from the river by I-95 include Market, Chestnut (excepting a motor vehicle viaduct connection to Penn's Landing and Market Street), Walnut (excepting a pedestrian overpass to Penn's Landing), Pine, Lombard, South (excepting a pedestrian walkway over the highway), Bainbridge, Fitzwater and Catherine. Not to mention Willow, Noble and Poplar Streets in Northern Liberties and numerous minor streets and alleys leading to the river all along the Delaware.

9

A

RCH TO

M

ARKET

I

NVENTORS AND

M

ILLIONAIRES BY THE

D

ELAWARE

(E

NTER

S

TEPHEN

G

IRARD

)

Arch Street was first called Holme Street, after Penn's surveyor, Thomas Holme. Then it became Mulberry Street.

Early on, this eastâwest lane was dug down east of Second Street to make it level with the Delaware shoreline, in order to allow for easier access to docks and ferry slips at the end of Mulberry Street. A single-span arched bridge was constructed to carry Front Street over the lowered road. Hence, Philadelphians began to refer to Mulberry as “the arch street.” The stone archway was taken away in 1721 after falling into disrepair and becoming a public nuisance, as Watson notes at length in his

Annals

. But the name stuck.

T

HE

A

RCH

S

TREET

W

HARF

There were two sets of bank steps on this block, along with five alleys passing through various wharf facilities built atop made-earth east of Water Street. The northernmost set of steps between Front and Water connected to Old Ferry Alley, which led to the ferry landings on the river.

One of these was the Arch Street Wharf, constructed in 1690 and prominent in colonial times. It was here that an unclaimed shipment of coffee was left to rot in the hot humid summer of 1793, leading Dr. Benjamin Rush to conclude, incorrectly, that this was the source of Philadelphia's deadly yellow fever epidemic that year (more about this in

chapter seventeen

).

The Arch Street Landing remained at the heart of the city's commerce on the Delaware River well into the 1800s. It was located approximately where Delaware Avenue and Highway 95 run in front of Pier 5 Condominium today.

Watson relates an amusing incident that occurred in the 1730s or so just west of the wharf/landing at what was once 87â89 Water Street: “[O]ld Anthony Wilkinson had his cabin once in this bank, which got blown up by a drunken Indian laying his pipe on some gunpowder in it.” The place where this happened existed for over two centuries afterward, becoming part of Philadelphia's lore first through eyewitnesses and then through John Watson's chronicle. That spot no longer exists owing to I-95.

J

OHN

F

ITCH AND

O

LIVER

E

VANS

The era of the steamship began at the Arch Street Wharf on July 20, 1786. It was from there, on that date, that Pennsylvania-based inventor John Fitch (1743â1798) navigated the first vessel ever successfully driven by steam. The test of his small skiff on the Delaware River was the earliest practical application of steam power to navigation in the world.

The next year, Fitch made the first public demonstration of a steamboat in the presence of delegates from the Constitutional Convention, which was then in session at the Pennsylvania State House (Independence Hall). Simply named

Steam-Boat

, Fitch's cumbersome craft was forty feet long and had six paddles on each side connected to a twelve-inch cylinder steam engine. It made three miles per hour against the current.