Please, Please, Please (14 page)

Read Please, Please, Please Online

Authors: Rachel Vail

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Social Themes, #Friendship, #Family, #Parents, #Performing Arts, #Dance, #Fiction, #General, #Social Issues

“OK,” she whispered, touching my hair.

“Because even if you think it’s stupid to want that, I just, I want, I don’t want to think about my career. I’m twelve—”

“I know,” she interrupted, but I jumped right back in.

“It’s hard because, I love when you look at me like I’m special.” Her eyes were steady on mine. I didn’t look away. “And you do everything for me,” I said. “You give me so much. I know I have a gift and opportunities, and I want you to be proud, and, God, I don’t want you to stop looking at me.” I took a breath and stared down at my dirty sneakers. “But also I want to, to lose a three-legged race. I know that’s ridiculous but I just, that’s what I want.”

A car passed outside, its tires sticky-sounding on the pavement. I raised my eyes to my window and focused on the streetlight, letting my vision blur.

Mom touched my forehead, lightly, and slowly brushed the hair back with her palm. “OK,” she said.

“Thank you,” I whispered, without taking my eyes off the light outside.

She pulled her arm back and rested her head on her knees, mirroring me. “You know,” she said, “you don’t have to be exactly like me for me to love you. But you do have to let me know who you are, and whoever that is, I’ll love.”

But not be proud of

, I thought, looking at her. I didn’t want her to have to lie, though, so instead of making her promise to be proud of me, I just asked, “Promise?”

“I’ll always love you, no matter what.” She reached across my knees to hug me. It didn’t quite work. We were both off balance and cramped, so we ended the hug quickly and smiled little grins at each other.

I pulled off my sneakers, for something to do, and said, “Thanks.”

“Don’t ever worry about that,” she said, spinning my dinner plate a quarter turn.

We were both trying to pretend everything was all patched up, I could tell, and though I had been sitting here promising myself no more lies, I still didn’t have the courage or the words to be honest about everything still not feeling OK. “OK,” I said. We both smiled again without showing any teeth and let out deep breaths.

She bit her lip but didn’t look up at me. “I just wish we’d been able to discuss this before.”

“I’m sorry,” I said, straightening my legs.

“Paul was sure you had run away.”

“Really?” We looked at each other.

“He felt he’d hurt you by saying he wanted Zoe to be his sister. He was sure it was all his fault.”

“Oh, Paul.” I sighed.

Mom shrugged. “None of us knew what to think. It’s just so unlike you to do anything like this.”

“Daddy hates me.”

“No,” Mom said. “He loves you. But it’s going to take him some time to finish being angry about this.”

“I’m sorry,” I said again. “You should punish me.”

“The point isn’t punishment, CJ.” She stood up. I watched her perfectly white Keds step gracefully across my floor, over my dirty ones, half a size smaller. It had started to drizzle, which I hadn’t noticed. She slammed my window closed. “The school is going to punish you, anyway, to make an example of you. Mrs. Johnson said you’re going to have in-school suspension for the rest of the week.” Mom leaned against my wall, crossing her arms over her chest. Lightning crackled in the sky behind her.

“Really?” I asked.

She nodded as thunder boomed. “I’m not sure what that is, actually.”

“Everybody will stare at me all day,” I explained. “You have to sweep the auditorium and Windex the front doors and, in between, sit in a chair outside Mrs. Johnson’s office, doing nothing.”

“Ooo,” Mom said. She slid down to the floor, bumping into my dinner plate. “Well, but you know what? I’m not going to intercede with Mrs. Johnson. I’m not going to ask her to go easy on you.”

“Good,” I said, moving the plate out of her way. “You shouldn’t. I guess. All week?”

Mom stood up and straightened her slacks. “That’s what she told us.”

I nodded. “Mom?”

“Mmm-hmm?”

“I really am sorry.”

“Me, too, CJ,” Mom said, standing up again. “Me, too.”

She left without kissing me. I sat in the corner for a long time, watching the rain.

twenty-three

I

have a very complex relationship

with Tchaikovsky. Also with my mother.

I sat on the bench, banging my new cleats against the firm-packed dirt and imagining myself dancing the final adagio from Tchaikovsky’s

Swan Lake

. As I died long-necked and alone in the spotlight, Coach Cress called my name. I looked up slowly. She sent me out onto the brown field, where I ran around in circles far from the soccer ball for the final three minutes until the ref’s whistle blew and I found myself in the crush of purple jerseys that meant we had won. Through the bodies of my friends, I looked to the sidelines where my mother sat solemnly among the other chattering mothers. I turned away and followed my best friend, who’d scored two goals off the girls whose fingers we now brushed as we mumbled, “Good game.”

After, at the pizza place, my teammates grabbed slices steaming hot off the tins and recounted the game, nodding, chewing. My mother had gone home, as I’d asked her to. I knew she was sitting straight-backed on her cow-stenciled stool, working up a smile for the daughter who had chosen to slump in clean cleats on a middle school soccer bench instead of to dance in the spotlight. As I pictured her, the

Swan Lake

music in my head drowned out my friends’ voices.

Turn the page

to get a first look at

Morgan’s story!

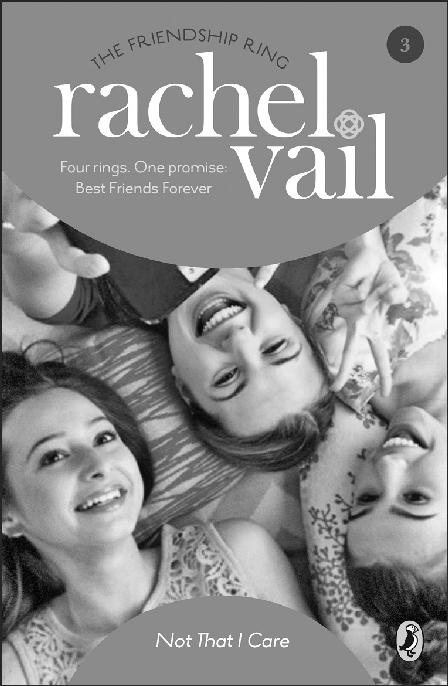

Not That I Care

one

n

o way. I didn’t know we were going to have to stand up in front of the entire class. There’s no sound in the classroom except the

click, click

of Mrs. Shepard’s pointy pumps on the tile floor. She’s behind me now, so I can’t see her. She hasn’t even said hello. Creative writing and American history are too important, I guess, and we are too shockingly ignorant to waste a second. Mrs. Shepard seems insulted that our sixth-grade teacher thought we were ready for her class.

“When I call your name,” she says, “please bring your Sack to the front of the room and stand beside my desk.”

I don’t know what to look at. This is a new thing with me. Lately my face has trouble knowing what to do. I catch myself blinking too hard, or chewing my upper lip, or with my mouth hanging open. My face can’t relax, like it used to. It doesn’t quite fit me anymore.

I blow my bangs off my eyelashes and try to sit still.

Count to five without moving

, my mother keeps telling me,

I can’t stand how fidgety you are lately, Morgan

. One, two, three, I can’t do it. I have to shift my shoulders around.

“Bring Yourself in a Sack” Mrs. Shepard called this project when she assigned it last Friday as part of our unit on creative writing. There was a brown paper lunch bag on each desk when we got to class after lunch. Mrs. Shepard said, “Fill the bag with ten items that represent you in all your many aspects.” Maybe she said facets. Either way, I thought it sounded like a cool project.

Lou Hochstetter, who sits behind me, had complained that we don’t usually get homework over the weekend. Mrs. Shepard raised one eyebrow and stared at poor Lou for a mini-eternity, until he sunk down so low his feet clanged my chair’s legs. “Welcome to the seventh grade, Mr. Hochstetter,” she said. That cracked me up.

After school, my best friend, CJ Hurley, got asked out. She called me right away to tell me, of course, but I was out riding my bike around. Friday had been a stressful day, socially. CJ left me a message on the machine: “Hello, this is a message for Morgan—Morgan? Tommy Levit just asked me out. Call me.” All weekend I kept meaning to call her back, but I just didn’t get a chance. Not that I wasn’t happy for her. I don’t like Tommy anymore.

I just really got into this project, searching for ten perfect things. I barely talked to anybody. “Bring Yourself in a Sack?” my brother asked. “I remember that project.” But I didn’t want his help.

I was in a great mood when I got to school this morning, with my Sack full of ten complicated, meaningful symbols. The janitor was just unlocking the front doors, I got to school so early. I slid my bike into the rack and waited on the wall for CJ.

When her mother dropped her off, CJ ran over and climbed up onto the wall beside me. She didn’t say anything about my not calling her back; she knows I’m really bad about that and she’s used to it. Or I thought so, anyway. We talked about Tommy. I told her not to worry that they didn’t talk all weekend, after the asking out; when I went out with him last year he never called me, either. Then we talked about whether Tommy’s twin brother, Jonas, would ask me out today, like he was supposed to, and how fun it would be if the four of us were a foursome, and whether or not Jonas’s curly hair is goofy. CJ used to like Jonas, but now she’s going out with Tommy, which is fine with me.

Not that she cares.

I guess actually, now that I think about it, I was doing all the chatting. CJ wasn’t saying anything about becoming a foursome. She was just sitting there all pale, her deep-set green eyes looking anywhere but at me, her tight, skinny body even tauter than usual. I didn’t notice she was acting weird until too late.

Anyway.

Mrs. Shepard is walking up toward the front of the class. I hold my breath while she passes me. When my brother, Ned, was in seventh grade, four years ago, he said Mrs. Shepard was “real” because she wouldn’t paste stars on every pretentious, childish poem full of clichés. I took my poem off the refrigerator. I vowed I’d make Mrs. Shepard like me when I got to seventh grade. So far she doesn’t, particularly, but it’s only the third week of school. I still have a shot.

I’m lying low in my seat now, clutching the bag and squeezing my eyes shut as Mrs. Shepard speaks. “I want to hear a clear, concise explanation of each item, why you chose it, and what about your character, the item symbolizes.”

We have to explain? I would’ve chosen all different things.

I don’t know what I was thinking would happen with this Sack. Definitely NOT that I would have to unload my life from this brown paper bag like spreading my lunch on the cafeteria table for everybody to inspect and judge. No, no. Thanks anyway.

“Are there any questions?” Mrs. Shepard asks.

Right. Nobody raises a hand with a question, of course. I can’t look around to see if everybody else seems relaxed and ready, if it’s just me who’s hiding under a desk.

“Good,” Mrs. Shepard says, turning her helmet-head to look at each of us. Her white-blond hair is pasted into the kind of hairdo that never moves, the kind that only gets washed once a week, at the beauty parlor. She reminds me of an owl, with her round, piercing eyes and small hooked nose. Maybe it’s the way she rotates her big head that’s plunked deep between her shoulders. I did a report last year on owls. They’re birds of prey. I sink down lower, imagining myself a field mouse trying to camouflage with the fake wood and putty-colored metal of my desk.

Please don’t call on me.

“Olivia Pogostin,” Mrs. Shepard calls.

Olivia Pogostin is my new best friend, as of today. I whispered with her all through lunch, which was a little awkward for both of us, but we managed. She was actually sort of witty, and she gets the pretzel sticks that come in an individually wrapped box in her lunch, definitely a plus. My mother would never waste the money on those. We buy economy-size everything, then take how much we need. We have one type of cookies for weeks at a time, until we finish and go back to Price Club. If there’s a big sale, she might let us get a sleeve of individual potato chip bags. I always feel good if I open my lunch and there’s a small sealed bag of chips in there. It looks so appropriate. CJ just gets a yogurt, every day, a yogurt, and that’s it. Not that they can’t afford more. She just has to worry, because of ballet.

I sort of liked Olivia today at lunch. Not as deadly wonkish as I had always figured. She had some funny things to say about girls like CJ who forget their friends as soon as a boy calls her on the phone. And, of course, there’s the pretzels.

Olivia walks up to the front of the class. Her coarse black pigtails don’t bounce, just jut adamantly out to the sides. She’s the smallest person in seventh grade by a lot, and also the smartest if you don’t count Ken Carpenter.

Olivia places her brown paper bag on Mrs. Shepard’s desk, turns to face the class, and says in her calm, steady monotone, “So. This is me.”

What am I going to do? I can’t present my items. My palms are starting to sweat on the brown paper of my Sack. This is me? No way I would ever get up and say This is me. Especially with this unexplainable stuff to explain.

Olivia pulls a charcoal pencil out of her paper bag, holds it up in front of her serious face, and announces, “Charcoal pencils, because I like to draw.” She places it on Mrs. Shepard’s desk blotter. Mrs. Shepard is nodding, over by the door. Teachers love Olivia; she does everything right. I didn’t know it was supposed to be like hobbies.