Plymouth (13 page)

Authors: Laura Quigley

The doomed

Terra Nova

expedition at the South Pole: Robert F. Scott, Lawrence Oates, Henry R. Bowers, Edward A. Wilson, and Edgar Evans. (LC-USZ62-8744)

Just 140 years later, Plymouth-born Robert Scott would be the man to prove Cook wrong in his assumptions, though Scott and his men would die in the attempt. March 2012 was the 100th anniversary of the death of Captain Scott and his men in the Antarctic. His final farewell letter sold for over £160,000 at auction in London, in which he pledged he and his team would together ‘die like gentlemen’. The letter was written on 16 March 1912, as his men succumbed to starvation and hypothermia in a blizzard, just 11 miles from a food depot.

Robert Falcon Scott was born at Milehouse in Plymouth – a plaque there commemorates his links with the city. In January 1912 he led an expedition to be the first to the South Pole, but they were beaten by Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen by just one month. Scott and his team perished in the Antarctic wasteland, in temperatures of -40 degrees Celsius – it was freak weather even for the Antarctic, the winter unexpectedly arriving hard and early. Their frozen bodies were not discovered until February 1913, and a memorial to his enterprise was erected on Mount Wise.

![]()

James Cook died and was buried at Ford Park Cemetery in Plymouth – not James Cook, famous captain of the

Endeavour

, but the dock worker James Cook, who was killed in an explosion on 13 December 1893 at Sutton Pool.

The

Standard

reported on 23 January 1894 that James and his colleagues had been working on deepening the harbour, which involved using a wrought-iron pipe to place explosives on the seabed; this was used to break up the rock so that dredging could commence. The top of the pipe was placed level with the dock and the explosives pushed down into the pipe using a long pole. Tragically, it seems that thick clay from the seabed glued the explosives to the end of the pole. As the pole was brought back up, the explosives came back up with it. Then the dynamite exploded, killing two dockworkers, including poor James Cook. A verdict of accidental death was recorded.

![]()

But the enterprise was more than just a race to the South Pole. Scott was a dreamer, an adventurer, but also he was an explorer, just like Cook. For Scott, this Antarctic wilderness was a final frontier to be documented and discovered in all its harsh beauty. Although their mechanical sledges failed them and all their ponies had to be shot, unable to survive the bitter conditions, Scott’s journey was one of remarkable discoveries. Scott and his team collected 2,000 specimens of animal life, including – for the first time – the eggs of the Emperor Penguin. His specimens are still the baseline by which the effects of chemicals and climate change are measured today. He was also the pioneer in the use of the camera for biological research. Even while struggling to return from the Pole, Scott took his men out of their way to explore a moraine near Mount Buckley, where he discovered fossils that proved the prior existence of the ‘supercontinent’ of Gondwana when the Antarctic lands had existed in a temperate climate. Scott became not only a legend and a tragic hero, but was also the founder of modern Polar science.

1797

MUTINY!

I

N THE MIDDLE

of the wars against France, and the constant threat of a French invasion of England, the worst possible event occurred in 1797 – the British Navy went on strike. With the French Revolution and the publication of Tom Paine’s

The Rights of Man

came an atmosphere of discontent aboard the ships, and a seaman’s life was hard. They had not had a pay rise in 100 years. In fact, with the costs of the wars escalating, most sailors had not been paid at all for the previous two years. Barely 15 per cent of sailors were volunteers; the vast majority were conscripted or impressed, many as a result of being caught as smugglers. During the Napoleonic Wars, 103,660 deaths were recorded, 82 per cent dying from disease, 12 per cent in accidents or shipwrecks and only 6 per cent in enemy action. Combine this with the dreadful conditions on board and punishments such as flogging with a cat-o-nine tails, and it was no wonder that the Navy was an unhappy place of work.

![]()

In the eighteenth century women sometimes enlisted in the Navy, often to be near their lovers. Only breaches of discipline or sudden illness might mean discovery when they had to remove their clothes. In 1761, Hannah Whitney was in male attire when she was seized by a press gang and sent, with others, to work in Dock. She served as a marine and it was only to avoid flogging that Hannah finally revealed her sex. She had fought in many battles – and left the Navy whenever she felt like it, simply by resuming her normal attire.

![]()

In Plymouth, six Irish sailors had been hanged from the yard-arm for fermenting discontent. Suddenly there was news that the Navy ships at the Spithead and Nore anchorages had gone on strike. The Plymouth sailors cheered and raised the red flags, refusing to work. The Plymouth agitators were initially satisfied by a shilling a day increase and a promise not to make examples of the ringleaders, but petitions at Spithead went unheeded and Plymouth re-joined the strike, evicting officers from the ships. Suddenly, England’s coastlines were undefended.

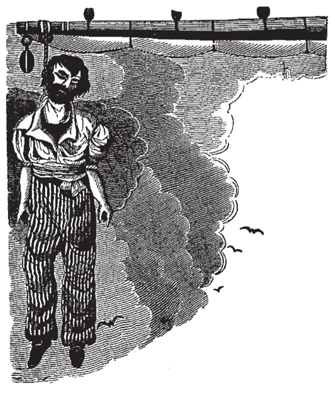

Flogging aboard a man-o-war. (LC-USZ62-46517)

The mutinous crews then went a stage further: they attacked the officers that remained. Those officers who had mistreated their men were raised into the rigging on ropes, amidst cheers and jeers from their rebellious crews. Meanwhile the town, initially sympathetic to the sailors’ plight, was given over to riot, and humiliated officers were paraded through the town and consigned to the Black Hole, a notorious prison on Fore Street. The houses of wealthy men were besieged (though the rioting achieved little more than hangovers and retaliation by the Navy, and was soon quelled).

The Navy retaliated in force. Lord Keith demanded the delivery of fifty of the most active mutineers or the punishment would include everyone. After quashing some further rebellion, Keith saw to it that fourteen men were condemned to death. Many others received 100 lashes apiece.

![]()

In the mid-1700s, a young grenadier was sentenced to 500 lashes for desertion. He appealed and the sentence was duly changed – he was ordered to be shot. He was taken onto the Hoe before his assembled garrison, forced to kneel for the last sacrament, and then, at the very last moment, the King’s Pardon was announced, to the cheers of all.

![]()