Plymouth (16 page)

Authors: Laura Quigley

Sir Astley Cooper was the most eminent surgeon of his day and regularly paid body-snatchers to help him with his research and to maintain his well-stocked museum of diseased body parts. When informed in 1820 that one of his former patients had died in Suffolk, Sir Astley set about retrieving the body for further study. Sir Astley had once performed surgery on the man and wanted to see how the ligatured blood vessels had fared in the intervening years, so he paid Thomas Goslin – at that time called Thomas Vaughan – to fetch him the corpse. Thomas and his associate were paid £13 and twelve shillings for their trouble, which included the cost of hiring a coach to transport the secretly exhumed body from Suffolk to London.

This was just the first of many corpses Thomas ‘retrieved’ for Sir Astley over a long career. He had come from Limerick to London with his family and as a youth had acquired a reputation as a ruffian. His first job as a stonemason’s labourer in a graveyard told him that there was more money to be made in desecrating the graves than in maintaining them. However, his success in London brought him into violent conflict with another successful grave-robber, so he hastened to Kent and for some time sent bodies to London from there. Thomas and his associates were nearly caught in Maidstone with a cart containing the freshly exhumed bodies of two men, two women and a child (or a ‘small’, as they were known in the trade). The officers who nearly apprehended them thought they were chasing smugglers, but were horrified to discover the stinking ‘product’ being smuggled.

Thomas fled Kent for Berkshire. By the time the Maidstone police caught up with him, he was serving three months in Reading gaol for stealing a body from a churchyard in Bray. On his release he was arrested again and taken back to Maidstone, where he promised to pay £100 bail – and promptly disappeared.

He then reappeared briefly in Sussex, it is thought, where he purchased a dead woman’s body from her own husband and then established his trade again in Manchester and Liverpool. An old adversary informed the police of Thomas’ whereabouts, and he finally stood trial in Maidstone for the five bodies found on the cart. Again he escaped, this time by sawing through the bars in the cell window and using his bed-sheets as a climbing rope.

Back in Manchester, his associates had been discovered in a stable, cramming corpses into 2ft-long boxes for transport. Even though his friends were in custody and he was on the run, Thomas still had the audacity to visit St Mark’s churchyard to survey the prospects and ask the stone-cutter there about any funerals that day. The stone-cutter alerted local officials and sentinels were placed to try to catch the robbers. At midnight two men appeared and started digging – they were fired upon but escaped apparently unharmed.

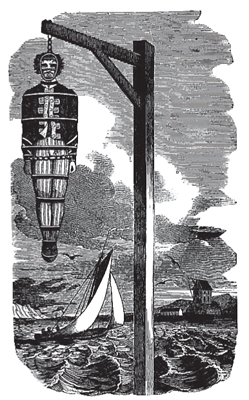

Thomas Goslin in action!

A Maidstone constable, hearing of the event, then travelled to Manchester and apprehended Thomas while he was having his breakfast. Thomas tried desperately to escape but found himself trapped by the bars on a casement window. He spent two years in prison at Maidstone.

His arrest caused a national outcry, for when they examined the burial grounds in Manchester locals discovered 200 bodies had been stolen, never to be seen again.

Thomas was one of the ten best ‘resurrection’ men of his day, his work often undetected. He used all the best methods. Wooden shovels made less noise than metal ones. His ‘dark lanthorns’ shone only a narrow beam of light as his team dug a hole at the head of each grave and exposed just the top third of the coffin. Using the remaining earth on the coffin as a counter-weight, the snatchers ripped open the lid and with hooks pulled the corpse from the grave head-first. They stripped the corpse and left the clothes in the coffin – so as not to be caught as thieves, the penalty for theft being much more severe than that for stealing a corpse. The coffin was then covered over with the same earth. Thomas cleverly used cover sheets on the sides of the grave, so the surrounding earth would appear undisturbed.

Alternatively, his team would start a tunnel a few feet from the head of the grave, and break open the top of the casket, pulling the bodies with hooks all the way back up through the tunnel, never disturbing the earth over the gravesite at all. Uninterrupted, the team could remove a dozen bodies in a night, piling them onto a cart for transport. The bodies were then packed into crates just 14in wide and deep, and 2ft long; a macabre courier service.

Women were vital to the body-snatching trade, though ironically it would be women who would end Thomas’s career. The female accomplices would mingle with the mourners at the funeral, and ask questions about the condition of the deceased. They would also appear at workhouses, pretending to be relatives of the sick and dying. Once by the bedside, they would claim the corpse. A cart could then take the fresh body directly to the medical school for sale. They didn’t come much fresher than that.

![]()

Stoke Damerel churchyard was also the location of a wicked murder. In 1788, Philip Smith, a clerk from the Survey Office, was killed in the churchyard by a severe blow to the head. Eventually two murderers were caught: William Smith and John Richards, who had been seen together near the churchyard at the time of the murder.

Richards was a disreputable character who had been sacked from the dockyard and previously involved in numerous violent altercations. It seems William Smith had been offered payment if he helped Richards take his revenge against Philip Smith. Though they denied this, both Smith and Richards were sentenced to be hanged at Heavitree Gallows in Exeter and, by order of the judges, their bodies transported to a gallows at the edge of Stoke Damerel churchyard, by the creek once there, where their corpses would be kept hanging in iron cages until they had rotted.

It took seven years for the bodies to rot, pecked at by birds, blown apart in storms. The cage containing William Smith’s body finally broke free and his body was then interred under the gallows, unmarked, while Richards’ body simply disappeared, probably falling into the river and washing away. The gibbet itself rotted and fell into the river in 1827, and a local carpenter made a fortune making snuff boxes from its wood.

![]()

Of course, the trade created outrage amongst the grieving relatives and friends. To have paid for a decent burial only to have the body so desecrated was an abomination. Many still believed that, come the resurrection, their deceased needed to be intact. Only murderers, their souls already damned, were seen as fit material for anatomical dissection. Relatives paid small fortunes for secure tombs and rented mortsafes – locked iron cages that enclosed the coffin after burial, until the deceased had decayed sufficiently to be of no further interest to a bodysnatcher. Churches would hire out mortsafes and set up watch-towers over burial grounds, but the trade continued, unabated.

After being released from prison, Thomas established his trade again in Great Yarmouth. Calling himself Thomas Smith, he set up a house and stable and hired new accomplices. Then he paid the sexton of the local church, Jacob Guyton, to provide him with information on funerals. Soon, though, rumours began to spread of grave-robbings. Thomas was one for the ladies, and while trying to seduce a young local woman he seems to have let slip details of his trade. The chief of police informed the sexton – without realising that Guyton would then help Thomas and his associates to escape.

George Beck was a baker in Great Yarmouth, whose wife had sadly died in childbirth in October 1827. Concerned by the rumours, he anxiously uncovered his wife’s coffin on 4 November. To his horror, he discovered that her body was gone; only her burial gown remained. He was devastated. Soon the cemetery was crowded with grieving townspeople searching for their deceased relatives, frantically digging out the graves and revealing that twenty bodies had been taken. One onlooker remarked that the churchyard now resembled a monstrous ploughed field.

The police eventually captured Thomas’ accomplices, who quickly gave him up. On hearing of Thomas’ arrest, the townsfolk turned into an angry mob. Labelled the ‘monster fiend’, Thomas needed a police escort to the courthouse. His old friend Sir Astley Cooper paid Thomas’ bail and Thomas left the gaol disguised as a sailor to avoid the crowds baying for his blood. Sir Astley covered Thomas’ expenses at the trial, and even paid Thomas’ wife ten shillings a week while Thomas served six months in the gaol at Norwich Castle.

On his release, Thomas was immediately back in business – this time at the Red Cow pub in Colchester where police discovered three bodies, one of them a dead baby wrapped in a handkerchief. The grisly corpses had to be displayed for their grieving relatives to identify them. Thomas faced trial again, but was freed due to lack of evidence – no one had actually seen him exhume or transport the stolen bodies.

Thomas realised he needed to move to a new location, and saw Plymouth as a viable destination. Stoke Damerel church was ideal: it was secluded, surrounded by high walls, and received a regular supply of new bodies from the swelling population in Devonport.

And there was another bonus – ghosts! The townspeople did not like to walk past the churchyard, as it was thought to be haunted. A gibbet with a horrifying history had stood on the edge of the churchyard for many years and had only recently blown down. Also, the saucer-eyed ghost of a waterman had been seen, thought to haunt the churchyard because his widow had so quickly found herself a new husband.

All in all, it was an ideal location for nightly endeavours – and soon the dead of Devonport were in regular transit to the anatomy schools of London.

However, Charles’ taste for young women would once again bring about his downfall. He was soon making advances to a pretty servant girl who lived across the road. She rejected him, and furthermore she informed her master that she did not trust the new neighbours. The suspicious master kept an eye on the newcomers and, after witnessing some strange behaviour, reported his suspicions to the police. The neighbour assumed that he had captured a ring of smugglers, but he was to find that his new neighbours were something much, much worse.

The head of the police, Richard Ellis, formerly a London Bow Street officer, decided to see these miscreants himself, and wandered into Stoke Damerel in disguise. There he discovered Richard and Mary Thompson, alleged servants to Thomas Goslin, loitering in the churchyard, while two coffins entered the church. As he watched, Mary Thompson approached the mourners over each grave. Mary remained in the churchyard for a few more minutes before following her husband back to their residence at No. 4, Millpleasant.