Plymouth (18 page)

Authors: Laura Quigley

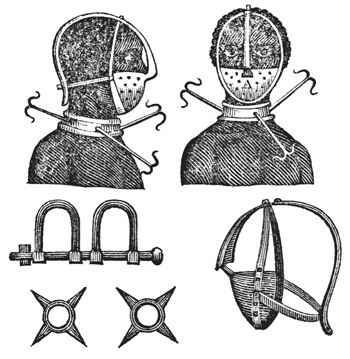

Torture devices used on slaves, as reported to Darwin: collar, gag and pronged neck collar. (LC-USZ62-31864)

The atrocities Darwin witnessed in the countries visited by the

Beagle

would harden him against all forms of exploitation. While waiting in Devonport, Darwin received word of the failure of his cause in Parliament. The Slavery Abolition Act was finally passed in 1833 while he was at sea.

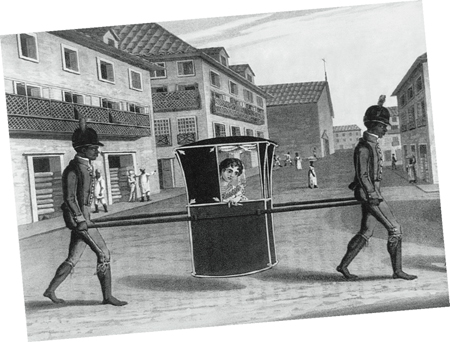

Arriving in Bahia, Brazil, where 41 per cent of African slaves were landed, Darwin was appalled to discover that everyone he met who wasn’t a slave owned at least one slave. As Captain Fitzroy was carried by slaves, in a sedan chair, into the town, Darwin roamed around the sweltering streets and discovered hundreds of slaves at work, and stories of horrific abuses – murder, and torture with gags, shackles and pronged collars. Escaped slaves frequently committed suicide, throwing themselves off cliffs rather than suffer re-capture.

Slaves carrying a sedan in Brazil, such as transported Captain Fitzroy. (LC-USZ62-97215)

It seemed that the restrictions on transporting slaves were only driving the slave trade underground and making it all the more brutal. In Montevideo, the

Beagle

came under the protection of the HMS

Druid

, who had just captured the

Destimida

secretly transporting slaves. The captain and men of the

Druid

had searched high and low for slaves on board, without success –until an officer thrust his sword into a water butt. A pained cry from within revealed that five slaves had been stored away inside that one barrel. Forty more slaves were discovered jammed into the crevices between the water casks under a false deck.

During the voyage, Darwin saw evidence to refute the accepted truism of savagism – that the black slaves were a sub-species of mankind who could not be civilised. The prevailing argument was that it was not cruel to treat these creatures as slaves, just as it was not cruel to domesticate and work a farm horse. In fact, Darwin had found many of the slaves themselves perfectly ‘civilised’, and went on to prove his theory that mankind was all of one species.

![]()

In 1825, a slave woman escaped Jamaica and made her way to England – ironically landing first in Plymouth, Hawkins probably having transported her ancestors to Jamaica. Once in Plymouth, though, she was granted her freedom.

![]()

In the native tribes of Patagonia, Darwin met good-natured men and women with excellent abilities for languages. But these same people Captain Fitzroy regarded with horror, as ‘animals’ secretly capable of the worst barbarities. Fear, Darwin realised, was the primary source of racism, leaving the white traders seemingly oblivious to their own barbarities against black slaves.

Even after the Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, slavery issues still fermented debates, with slaves still working the fields in the southern states of America. Dr Charles Caldwell from Kentucky was a visiting speaker at a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in Plymouth in 1841, with Charles Darwin in the audience. (It is thought that Richard Owen announced his discovery of the dinosaurs at the same meeting.) The bombastic, slave-owning Caldwell refuted Darwin’s claims of the common origins of man and was determined to convince his audience that the black African was closer in appearance and intelligence to the higher forms of apes than mankind. Only whites, Caldwell believed, had any capability for culture. The science of ethnology, supported by Darwin’s former host, Captain Fitzroy, was still ranking and dividing the races rather than unifying them, a dangerous precedent for the racist propaganda that would sweep through Germany before the Second World War.

1700-1912

FIRE AND TEMPEST

J

UST 10 MILES

south of Rame Head is the Eddystone, a jagged reef mostly submerged at high tide, which has claimed countless lives in horrific shipwrecks over the centuries, ships literally sinking without a trace.

It was here, in 1700, that Henry Winstanley, a renowned dreamer of humble origins, achieved the impossible. It had taken him four years in stormy conditions, but he managed to build the first lighthouse on the slimy rocks at Eddystone. In just a few short years, its shining light saved hundreds of ships. But the Plymouth coast is notorious for gales, especially in the winter months, and November 1703 brought the worst storm ever to hit the southern shores. As the tempest ravaged Plymouth, smashing houses and wrecking ships, Winstanley defiantly remained in his lighthouse to finish some repairs. On the shore, the light from the Eddystone was still seen until midnight, flickering in the ferocious gales, but by the morning it was no more; only a few twisted iron beams remained rising from the bedrock. The lighthouse, with Winstanley still inside it, had been swept out to sea.

![]()

Mr Jones was the keeper of the lighthouse on the Breakwater, an astonishing construction built to calm the waters of Plymouth Sound. In January 1845 Mr Jones’ body was discovered on the Breakwater below the lighthouse. He had fallen to his death. Previously there had been horizontal iron rods around the lighthouse, constructed to allow work to go on above the tides. But the lighthouse keeper, deciding that they were no longer necessary, had just had them removed. If the iron rods had still been there, they would have broken his fall.

![]()

Subsequent lighthouses fared little better. Rudyerd’s Lighthouse, built of wood in 1709, was consumed by fire. As the lighthouse burned, the keepers clung to the Eddystone rocks, desperately awaiting rescue. One of the keepers, Mr Hall, looked up – and met a horrible fate when molten lead from the lighthouse dripped down his throat. Some stories say that when he died, aged seventy-five, a ball of lead was discovered in his stomach.

The Eddystone Lighthouse. (LC-DIG-ppmsc-08791)

Subsequently Smeaton’s Lighthouse, despite its excellent design, was undermined in 1877 – quite literally, as the water had eroded the rocks beneath it. The top of Smeaton’s Lighthouse now stands proud on Plymouth’s Hoe, a shrine to the god-like powers of wind, fire and water.

In 1796, before the construction of the Breakwater, a gale hit Plymouth with such incredible fury that the

Dutton

was wrecked. The ship had been making for shelter in the Cattewater, through monstrous waves and heavy rain, when she hit a shoal of rocks near Mount Batten and lost her rudder. Bereft of control, she crashed onto the rocks beneath the Citadel.

The

Dutton

was carrying 400 soldiers and many women and children: 500 people crowded onto the deck, desperately trying to escape as the waves crashed over them. The guns of the Citadel boomed out, calling for rescue, and a rope was cast from the shore – one end attached to a bolt on the ship, the other held by fishermen on the banks. Each passenger clung to a slippery iron ring and was pulled through the raging surf – half-drowning in the process, as the sea was starting to carry off the wrecked ship.

Amidst the chaos and confusion, Captain Edward Pellew of the Royal Navy, on shore, called for volunteers to board the

Dutton

and assist the passengers. From a terrified crowd only one man volunteered, a midshipman called Edsell. Pellew grabbed the iron ring and was dragged through the waves to the ship and immediately took charge, threatening to run through with his sword anyone who disobeyed him.