Plymouth (11 page)

Authors: Laura Quigley

When it came to hanging Carey, however, the executioner could not be found. A search discovered him hiding, drunk and senseless – overwhelmed by the horror of the occasion. A second executioner was appointed and at last Carey was hanged. Carey’s last words were solemn: ‘Judge and revenge my cause, O God,’ she said. This Quick took as proof that she ‘went into a lake of brimstone and fire, there to be tormented for ever and ever.’ Actually, it was very likely she was innocent.

1660-1822

DEAD MAN'S LOTTERY â A SMUGGLERS' GAME

B

Y THE DAWN

of the nineteenth century, Cawsand, on the south-western edge of Plymouth, was a smugglers' paradise. Even today, it is not difficult to imagine the men, by moonlight, pulling their small boats onto the concealed beach, amidst the cluster of inns and cottages, stealthily unloading their contraband of brandy, salt and silk. Bent double, shuffling through the tunnels under the houses, their women stealing away the goods into fish cellars and storehouses, or keeping a watchful eye out for the customs officers who might suddenly arrive by sea to catch them in the act.

Although the scene may be romantic, this illegal âfree trade' â as the smugglers called it â was anything but: it was a lottery where the risks were high, the work was hard, and many a tedious night was spent in bitterly cold conditions. Success brought wealth, but at the cost of many lives and much toil.

After the devastation of the English Civil War, England was financially in ruins â thousands were homeless. Even by the Restoration of King Charles II, the country still urgently needed money, and the age of the privateers returned. Of course, they hadn't completely disappeared during the Civil War: they were happily working for King Charles I raiding Parliament's naval forces all along the Devon and Cornish coasts.

After the war, Plymouth restored its beleaguered finances by stealing the wealth of other nations, ignoring any and all peace treaties. On 22 July 1660 two English ships entered Plymouth harbour, having commandeered three ships â one French, and two Dutch â laden with valuable trading goods and heading for La Rochelle. Another French ship, laden with wine and bound for Amsterdam, suddenly found itself âre-directed' to Plymouth, and its goods confiscated. Plymouth restored its fortunes by establishing its own âpirate' economy.

Of course, Plymouth was also making money through legal trade with Europe and the New World, and Parliament took its own cut of this wealth by establishing taxes on all overseas trade â taxes that would rise to ridiculous levels to fund wars throughout the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Customs officers were appointed in Plymouth, but their early efforts to control trade proved very unpopular. Goods that failed to pay the tax were confiscated, stored in great warehouses near the quay at Sutton Pool and often subsequently destroyed, much to the annoyance of the local population. In March 1679 the customs officers burnt illegally imported linen and canvas and staved in barrels containing 15 tons of French wine. The impoverished masses looked on in horror. In 1680, a further 30 tons of French wine, brandy and vinegar were dumped and French linen worth £2,000 was burnt.

Of course, the customs officers were not well paid and subsequently much of the contraband was never truly destroyed but simply disappeared. Customs officers were also notorious for taking bribes and stealing from ships. In 1595 Nicholas Halse, then controller of customs at Plymouth, was forced by the authorities to make reparations when the owner of the

Jewel

accused Halse of stealing valuable âconchinella' and âindico' from the

Jewel

's hold. In 1614 the attorney-general was again accusing James Bagge, Plymouth's new controller of customs, of abusing his position.

By 1680, things were no better. The King sent his official, William Culliford, to Devon to investigate rumours of corruption amongst the customs officers, and Culliford was appalled to discover that the Plymouth officers were the most corrupt in the country, engaging in every kind of scam and larceny imaginable. The controller of customs at Plymouth was dismissed, and the service completely overhauled, but still the corruption continued.

No wonder then that smuggling became a major occupation in Plymouth and along the surrounding coastlines â corrupt officials, high taxes on imported goods, a lucrative trade with Europe just a short sailing distance away. The fishermen of Cawsand, skilled sailors and ship-builders all, saw an opportunity to make a little extra money, and took every advantage of the local conditions, knowing that, while the ships in Plymouth Sound were often stalled by southerly winds, Cawsand harbour was the ideal setting-off point into the Channel. The customs officers just couldn't catch them, even when they wanted to.

Soon, inns around Plymouth became storehouses for contraband â spirits, sugar, tobacco, and coffee. Even a church was a viable depot: Cawsand's local vicar was showing the rural dean around the top of the church tower at Maker church when he looked down to see twenty-three tubs of illegal spirits stored in the gutters. A tub of spirits left on the church doorstep the following morning bought the vicar's silence. While they benefited, the community simply kept quiet â and enjoyed a good drink to boot.

In 1747 the mayor, aldermen and merchants of Saltash complained to the lords of the Treasury that smuggling was becoming a major impediment to legal trade. The River Tamar was overrun with smugglers, all making use of the creeks and inlets around the Tamar to land their goods illegally. The mayor requested additional customs officers and searchers, but the Treasury refused the request, expecting Plymouth to foot the bill â which it didn't. Plymouth was making too much money out of smuggling.

And so smuggling increased in scale and daring. By 1780, 17,000 casks of spirits were being landed each year at Cawsand. The risks were enormous and the money to be made incredible. From a little âmoney on the side' for peaceful fishermen, the trade developed into a war of the sea â and it soon became a very bloody battle.

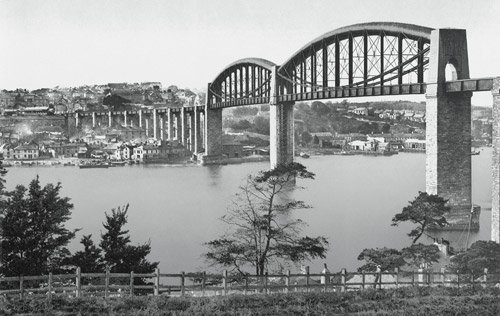

The Tamar River near Saltash, infamous haunt of smugglers. (LC-DIG-ppmsc-08788)

On a dark night in 1785 the

Happy-Go-Lucky

and the

Stag

, two smuggling vessels just returned from Guernsey, were quietly landing their cargo on the west of the Rame peninsula when the customs' boat

Pylades

discovered them. A midshipman of the

Pylades

secretly boarded the

Stag

, carrying a musket, but was spotted and the alarm was raised. As the

Stag

's captain came up on deck, carrying a blunderbuss and preparing to defend his ship, the

Pylades

' midshipman opened fire â and blew a hole in the captain's midriff. The smugglers then opened fire on the

Pylades

, killing one customs officer and wounding two more.

âKill them all!' the smugglers cried. âDon't let one go ashore to tell their story!'

The smugglers escaped, but they were captured the following year in Falmouth. Ironically, the

Stag

had formerly been a customs' boat, mounted with eighteen guns, but was sold as unfit for use â only to be bought by a boat-builder in Cawsand and refitted for successful smuggling.

Harry Carter's name became infamously linked with Plymouth Sound. While running his illegal cargo into Cawsand one night, his ship, the

Revenge,

was suddenly boarded by naval officers. He and his crew fought valiantly, unarmed, until a Navy officer beat Carter senseless with a cutlass. Harry staggered and collapsed to the deck, only to come to while the Navy officers were busy securing Carter's crew in the hold. The wind was blowing hard from the south east and the

Revenge

ran aground, giving Harry his opportunity to escape. He crawled, unseen, across the deck and, in incredible pain, pushed himself over the side into the shallow water to struggle ashore across the rocks.

In Cawsand Harry Carter's brother, Charles, had been on lookout and gathered a team together to search the shore for any of their associates who might have escaped. They spotted Harry, still in his huge coat, almost lifeless, collapsed on the shore. They managed to hide him in the village and a doctor was sent for. An unnamed wealthy investor then hid Harry for three months, and he eventually managed to return to Cornwall, having escaped the customs officers for good.

But the violence continued. On a moonlit night in 1790 the smuggling ship

Lottery

was off Cawsand, unloading contraband spirits worth £6,000 into small boats, when the

Hind

, a revenue cutter with boatman Humphrey Glynn aboard, suddenly came alongside. The crew of the

Lottery

fired at the customs' boat, blowing Glynn's face off. It seemed that Glynn had his back turned to the

Lottery

while manoeuvring his ship, and the musket shot entered the back of his head and exploded out through his face.

In the subsequent confusion the

Lottery

escaped, but the hunt for the killer continued for two years. Glynn had been a respected member of the local community, married to a girl from neighbouring Kingsand. His death was a tragedy. Eventually, a smuggler named one Thomas Potter as Glynn's murderer and Thomas was taken to London and hanged.

The smuggling trade involved the entire community at Cawsand, as a visitor at the end of the eighteenth century described:

We descended a very steep hill, amidst the most fetid and disagreeable odour of stinking pilchards and train oil, into the town.... In going down the hill... we met several females, whose appearance was so grotesque and extraordinary, that I could not imagine in what manner they had contrived to alter their natural shapes so completely; till, upon enquiry, we found they were smugglers of spirituous liquors; which they were at the time conveying from cutters at Plymouth, by means of bladders fastened under their petticoats; and, indeed, they were so heavily laden, that it was with apparent difficulty that they waddled along.

After the capture of Napoleon, there were hundreds of naval personnel suddenly out of a job, and they entered the lucrative smuggling trade. The Cawsand smuggling fleet was expanded in 1815, with a fleet of cutters capable of shipping 1,000 five-gallon casks from Holland and France, as well as cargoes of silks, salt and tobacco.

For the local government the situation had become serious, and in the 1820s Plymouth supplied fourteen new revenue cutters to augment the existing services. Public sympathies, however, still remained with the smugglers, who faced terrible hazards defying what were seen as unfair import taxes. On 26 October 1822 the

Royal Cornwall Gazette

reported that a Cawsand-rigged smuggling boat from France had been totally lost on the previous Wednesday night near St Michael's Mount. The report continues: âwe regret to add all the crew drowned'. Despite the violence, the smugglers were rarely seen as criminals but as local people whose skills as sailors and navigators were greatly admired. They were sorely missed if they died in the appalling gamble that was âfree trade'.

1768

VOYAGES OF THE DAMNED

T

HREE TIMES CAPTAIN

James Cook set out from Plymouth on voyages of discovery that would explore the Pacific, discover the eastern coast of Australia, confirm the existence of the Baring Strait between Russia and Alaska, and circumnavigate Antarctica (the first man to do so). His discoveries would transform our knowledge of the world and its species, and open up communications and trade across the globe. However, they would also lead to the establishment of one of the most brutal convict colonies, in Australia; destroy the lives of native peoples in acts of genocide he could never have foreseen; and bring about his own horrific death at the hands of cannibals.

![]()

Sir Joseph Banks, the acclaimed botanist travelling with Cook on his first voyage, was unimpressed by the Australian Aborigines when he met them fishing in the mangroves and marshes around Botany Bay. He remarked that they were a dirty people, caked all over in smelly mud, even in their hair. Within hours of landing, however, Banks’ party were suffering from terrible mosquito bites, one of his team eventually dying from a resulting infection. In his diary, Banks pondered why the natives seemed so unaffected by mosquitoes, foolishly failing to make the scientific connection between the Aborigines’ smelly mud and mosquito repellent.

![]()