Poor Badger (2 page)

Authors: K M Peyton

Fi was hauling on the reins to steady him, but did not seem frightened. She saw Ros standing there and shouted, ‘Watch out!’ in a very imperious, bossy voice, but Ros did not move. She had as much right there as Fi, and Badger liked her, she knew. She wasn’t frightened. Fi shouted something rude to her and steered Badger past. His eyes were shining with half-excitement, half-fear, Ros thought. He looked barely under control. But Fi was strong too, and not afraid.

‘Ride ’im, Fi!’ her father shouted. ‘You show the little devil!’

The girl and the pony seemed well-matched. They were both fit and strong and bossy, and Fi circled and cantered and even galloped, and her family stood watching and applauding and shouting rude remarks. It was all very jolly. When Fi had got Badger tired, all the other children had a go, even the little one, with Dad running beside and crying out, ‘Of course you can trot – there’s nothing to it! Up down! Up down! Hold on, you little so-and-so!’

Ros stood there until it was nearly dark.

When they had finished, they put Badger back on his tether again and brought him a bucket of water from the car. Then, trailing the saddle and bridle, they all piled into a large car on the edge of the car park and drove away.

CHAPTER TWO

WHEN THEY HAD

gone, Ros went across to Badger. This time he looked at her rather nervously, not in his friendly, eager way of the first time. Ros rather got the message – ‘Oh, not again!’

‘It’s me, Badger. I’ve brought you some carrots.’

Although his owners had moved his tether peg, the grass was still rather trampled. The whole field looked rather trampled. And Badger had already drunk nearly all of the bucket of water they had left him. The pony’s coat was curly with sweat, and hot and damp under Ros’s hand. But the air had gone cool and sharp with the onset of dusk.

‘I can’t stay, Mum’ll be furious,’ Ros told him. She wanted to. She didn’t think Badger was happy. He was all stirred up with the fast riding, and moved about restlessly, pulled up

sharp

all the time by the tether. Ros talked to him softly, and she thought her presence soothed him. When she left him, he walked after her to the end of the chain, and stood and watched until she was out of sight. He whinnied after her once. She heard the whinny in her head all the way home.

‘I was just about to send out a search party!’ her mother said crossly (but not too crossly). ‘You can’t have been talking to a pony all that time?’

Ros explained.

It was hard to say exactly why, but she felt cast down by her evening. She didn’t like Fi very much, and Badger belonged to Fi. She tried to tell her mother this.

‘Well, they wouldn’t buy a pony if they didn’t want him, which means they must like ponies, doesn’t it?’

‘I suppose so.’

But her father Harry said, ‘Funny place to keep one, all the same. They’re not gypsies, from the sound of them.’

‘Well, that ground was part of a common, once. Before Safeway’s. It was all common land, before the railway and the arterial. I think they’ve got right on their side.’

‘Could get stolen.’

‘You’d have to take him through the town to get away! Out through the car park. I can’t see anyone risking that.’

‘I suppose not.’

When Ros was in bed, she lay thinking about Badger. In the morning she was off early for school, with more carrots in her

bag

. Leo wasn’t ready, and she wouldn’t wait.

Badger was standing with his head down, dozing, not looking as smart as the day before. His coat was curled and stiff with dried sweat. His water bucket was empty and kicked aside. But he was very pleased with the carrots and snuffled at Ros in his friendly way. Ros was longing to spend the day with him, take him for a walk to find some nice grass, and groom his lovely coat back to its sleek shine. But she knew Fi or Fi’s dad would come soon and see to him, move his tether peg and bring him some water.

But when she came home from school in the afternoon, no one had been. His kicked bucket lay where it had been in the morning, he was ungroomed and unmoved. He whinnied to her when he saw her, quite anxiously, she thought.

Ros went up and stroked and patted him, but she had given him all the carrots in the morning.

‘I’ll bring two lots tomorrow,’ she said to him. ‘And I’ll come back tonight.’

Fi and her dad must come soon, she thought, to look after him. He had no grass, only a beaten-down mud-patch. She was worried about him, and started to dream that Fi and her dad never

came

back, and looking after Badger fell to her and after a bit he became hers . . .

She told her mother about it all and her mother said, ‘He must be terribly thirsty by now. They’re bound to be back to see to him.’

‘Can I go?’

‘Yes. Look, I bought more carrots on the way home. But you mustn’t be so late tonight. You’ve got your homework to do.’

Ros gobbled her tea and ran.

When she got back to Badger the family were just arriving, this time just Dad and Fi and two of the small children, no mum. Dad pulled a five-gallon water-container out of his car boot and filled Badger’s bucket, and Badger drank the whole bucketful in one go.

‘You thirsty little blighter!’ Dad exclaimed. ‘You’ve drunk the lot!’

He sounded most surprised. But without more ado he put the saddle and bridle on and bunked Fi up on Badger’s back. Once more Fi trotted and cantered round and round the field until Badger was covered with sweat, then dad propped a pole up on a couple of oil cans and Fi jumped backwards and forwards over it, with much applause from her brothers and encouragement from dad. Badger was a very good jumper, Ros

noted

, but he got very excited and started to pull hard at Fi’s strong hands. Fi had obviously done plenty of riding and was in no danger of falling off, but she was a very hard and unsympathetic rider and, when Badger started to pull, she sat back and heaved on the reins. Badger pulled back and started to gallop. Fi steered him in a circle, hauling viciously on the inside rein, and eventually Badger came to a halt.

‘The little beggar!’ Dad shouted. ‘I thought he was supposed to be well-mannered!’

‘He’s terribly strong!’ Fi said, looking slightly anxious.

‘Yeah, too strong. If we give him less food he’ll quieten down I reckon. We’ll teach him, eh?’

So Dad did not move Badger’s tether peg, leaving the pony without any grass at all, nor did he refill the empty bucket, whether because he thought one bucket a day was enough, or whether to teach the pony a lesson Ros could not tell.

When they had gone, Ros stood miserably feeding Badger his carrots. She was now far more than anxious, in fact slightly desperate.

‘I shall move you, dear Badger. You can’t go all night without any grass!’

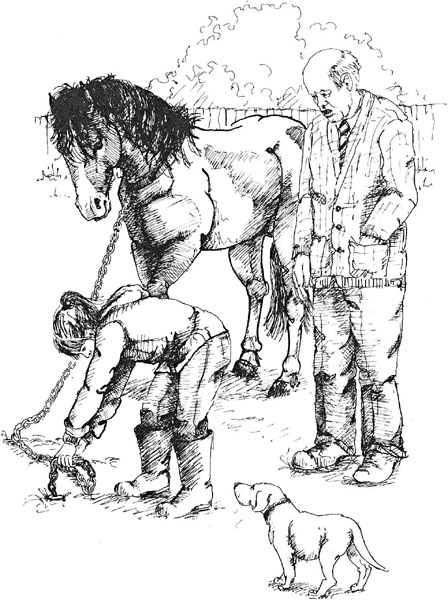

It was a terrible struggle getting the tether pin out. While she was trying, the old man who walked his dog came by. He lived in one of the houses that backed on to the waste ground at the far end, and Ros had always said hello to him. His name was Albert. He was a gloomy sort of man but his dog was nice and got lots of walks, Albert not having much to do all day and used to an outdoor life.

‘Watcha up to then?’

Ros told him, and he helped her. They took the peg to some new grass, not too far, in case Dad noticed. Ros didn’t think he would.

‘Funny way to keep a pony,’ Albert said.

‘They’ve left him without water!’

‘Aye, well, bring the bucket along and I’ll fill it for ’im,’ Albert said.

Ros walked back with Albert to his back-garden gate, carrying the bucket. She felt terribly relieved at the offer. Albert had worked on a farm most of his life, and knew about horses. Ros waited outside his back door while he filled the bucket.

‘Can you manage it?’ He sounded doubtful.

‘Yes. Yes, of course.’

It was very heavy, but she managed to struggle back to Badger without spilling much. Her feet were a bit soggy, that’s all. Badger plunged his nose in and drank about three-quarters of the water.

Ros was pleased with her work, although still very anxious about Badger’s treatment from his owners. Not giving him any food was bound to quieten him down, but surely there were better ways of soothing a high-spirited pony? But she had no time to linger. She had to run all the way home so that her mother wouldn’t be cross.

She told her parents all about it.

‘Sounds like they’re a bit ignorant,’ said her mother. ‘There’s a lot of cruelty to animals comes about by ignorance.’

Their dog Erm, now very ancient, had come from the rescue home. Her real name was Ermintrude and when they first had her she was very stupid and thin, because she had been shut in a shed and left all day and all night, but after living in a family and being treated properly for a while she became very intelligent and loving. But she was too old now to go as far as Badger’s field, and Ros only took her for short walks down the lane.

‘What can I do about Badger?’ Ros asked her parents.

‘He’s not yours. Nothing,’ they said.

‘Not yet, anyway,’ said her father.

Her mother ruffled Ros’s hair affectionately. ‘They must

want

him, after all. He’ll be all right.’

And with that Ros had to be content.

CHAPTER THREE

THE EVENINGS CONTINUED

in the same fashion, Ros going to see Badger and Fi coming to ride him.

Fi said to Ros, ‘Stary cat! What you always staring for?’

‘Who’s going to stop me, Bighead?’

Ros was no faintheart. She felt bitter towards Fi and her family for the brutish way they treated Badger. Badger was becoming more nervous and less friendly, and put his ears back now when once he had come forward with his little knucker of greeting.

‘But you love me, don’t you, Badger?’ Ros asked him anxiously, making up his diet with carrots and a bagful of porridge oats she had filched from the pantry. Once he saw who it was, Badger rubbed his head against her arm in his old friendly way.

He wasn’t as round and shining as he had been. His summer coat was scurfy and he was thin in the flanks. If it wasn’t for herself and Albert, filling his bucket every day, he would have died of thirst before now, Ros thought. Albert had had a go at Fi’s dad, but he had told Albert to keep his long nose out of business that didn’t concern him.

‘They are horrid people. I hate them!’ Ros told her mother.

Her mother was sorry that what had started as a great thrill and interest for Ros had turned sour for her. She knew that it was making Ros unhappy, seeing Badger badly treated, but there wasn’t anything she could do about it. It wasn’t bad enough for the RSPCA.

‘After all, although he’s on a tether, strictly speaking they do go and see him every day, and move him. He’s not exactly neglected.’

‘But there’s hardly any grass, even when they do move him. They’ve ridden it all down.’

One evening, overhearing Fi’s conversation with her dad, Ros found out that they were taking Badger to a horse show the next weekend, to enter him for a jumping class. Ros pricked up her ears, and decided to go too.

Leo said he would come with her.

‘You could enter Andrew,’ Ros said, grinning.

Andrew was the boss frog. Ros didn’t see how Leo could tell them apart, but Leo swore he could. Andrew had a spot on his back; he was the only one Ros could tell was different, but Leo had names for lots of them. Ros suspected he just said the names to impress her.

Harry gave them a lift to the horse show, which was about ten miles away. It was in a huge field, where lines of horseboxes and trailers were pulled up, and rings roped off for jumping and showing and the gymkhana. Ros knew about horse shows, and where to look, but Leo was very ignorant. He even thought small ponies were just young horses, and would grow into big horses later on.

‘Stupid! Ponies are ponies and horses are horses, however old they are!’

‘Well, nobody ever told me! If no one had ever told you, you wouldn’t know a tadpole would grow into a frog. Would you?’

Ros scowled.

‘Would you?’ Leo persisted.

‘Not if no one had said, no. You wouldn’t think so.’

‘Well then. No one ever said to me about ponies.’