Printer's Devil (9780316167826) (33 page)

Read Printer's Devil (9780316167826) Online

Authors: Paul Bajoria

“It’s nearly morning,” I said. I felt around in my pockets to make sure the things Cricklebone had given me back from my treasure

box were still there. Nick came and sat down on the planks beside me.

“What do you think’s happened?” he asked.

“I’m not too sure.” That was putting it mildly. I was struggling to make any sense at all, really, of what had happened tonight.

Suddenly, sitting here, I’d realized how tired I was. “The man from Calcutta,” I said, “was Mr. McAuchinleck in disguise.

That policeman in there. All the time. Except …”

“Except what?”

“Except your Pa’s just killed someone who looked exactly like the man from Calcutta. And took the camel off him.”

“And took the stuff from inside it,” said Nick.

“I suppose so.”

There were some more indistinct shouts from the shed, and then quiet. I was finding it hard to think of what to say next.

Several days ago now, Nick had said to me, rather disdainfully: “This ain’t a game, you know, Mog.” The words echoed in my

head, as though they were only really sinking in now. A lot of our adventure

had

seemed like a game at the time. Now, as we sat overcome by exhaustion on the filthy edge of the dock, it seemed serious and

terrible.

“What happened in the church tower?” I asked, at length.

Nick’s voice was low in replying, and when it came it wavered. “I had to climb up there. My Pa said Coben was hiding out in

the bells. But he wasn’t there so I waited.”

“And then he came back?”

“Mmm.” He didn’t want to talk about it. He looked down at the clump of paper and the other treasures I was holding in my hand.

“What have you got there?”

“Cricklebone gave them back to me,” I said, suddenly feeling embarrassed again as I fingered the peg doll and the fat, rough

oblong of Mog’s Book. “They’re the bits of paper I took from Coben’s hideout, and — a few other bits of stuff. You know I

told you they’d been stolen? Cricklebone had them all along.”

“What’s this?”

Nick’s eyes had fallen on the bangle — which, for safekeeping, I’d slipped over my wrist. To my surprise, he reached out and

pulled it off me.

“That’s my —”

“What are you doing with this?” he said.

I tried to think of something to say. He thought the bangle was a silly thing to have. And I suppose it was, a bit — but —

“What are you

doing

with this?” he repeated, suddenly aggressive.

“Nick,” I said, “give it back, you’ll drop it.”

He leaped to his feet. The bangle glinted in his hand, reflecting the torchlight from the shed and the dangling lamps of the

nearby ships.

“WHAT—ARE YOU DOING — WITH THIS?” he repeated.

I was bewildered. I didn’t really know the answer. I suddenly felt frightened of him, as I had when he’d started questioning

me about the name “Damyata,” back in the empty old house.

“It — it’s mine,” I stammered nervously. “I’ve always had it.”

“What do you mean,

always

had it?”

“Well — all my life. It’s from my mother.”

“You’re lying, aren’t you?”

“No, of course not. It’s —“

“It’s

mine,”

he shouted. “

I’ve

had it all my life, from

my

mother! What are you trying to do? Why are you pretending to be me all the time?”

“I’m

not

,” I said, “I’ve never pretended — I didn’t know —” I couldn’t understand why he was getting so angry, and despite myself

I felt tears welling in my eyes. “Give it back,” I pleaded, “I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

“Yes you do,” he said accusingly. “This is

my

bangle, from

my

mother, Imogen.

I

got it, with her letter, when I was a baby, so long ago I don’t even remember. So how can it possibly be yours?”

I felt very peculiar. He’d just accused me of pretending to be him — but now here he was, pretending to be me. What he said

couldn’t possibly be true; and yet somewhere in the back of my head things began to fit together. The letter he’d quoted,

back in the old house. He’d said “Imogen” then — a name no one had called me for years. But it wasn’t

my

name he’d been quoting at all …

“Nick,” I said, “I think I can explain all this.”

I couldn’t, of course, not yet. But I had the strange sensation that something incredibly important had happened, or was about

to happen. Far too important, really, to be true. The implications seeped and spread through my brain, a growing patch of

warm excitement, making me feel thrilled and sick at the same time. I

knew

, but I still didn’t quite understand.

Beneath my dangling foot something bumped against the oily wooden support which was holding up the jetty. I looked down, but

could see nothing in the leaden water. There was another bump. Lash dropped his head over the side, and barked three or four

times. I reached over, and with my arm stretched down to its fullest extent I could just feel something soft, touch some coarse

cloth, something in the water.

Now my heart went cold.

“Nick,” I said, reaching out an arm for him. He was still standing beside me, silent and suspicious. I was about to tell him

to come over and look, but then I realized it might be better if he didn’t.

“Mr. Cricklebone,” I called between clenched teeth, “Mr. Cricklebone!”

He brought the lamp. Its light shimmered over the dirty river and I think I remember screaming as it illuminated the bosun,

floating face down, his head knocking gently against the beam.

DEATH II

Once it was all over, it rained. Big, sooty drops fell through the heavy air, spattering and staining everything in the hot

city. It made the worn stones of the streets glisten and sent streams running down their curbs, which swelled out into pools

halfway across the road at intervals; it turned the dust of the back lanes into ankle-deep mud; it swelled the black river

and submerged the oil-smeared carpet of rags, bottles, and dead animals on the stinking slopes between the water and the embankment

walls.

Rumors buzzed around the city like fat black flies. The only certainty was that every story contradicted all the others. Tassie,

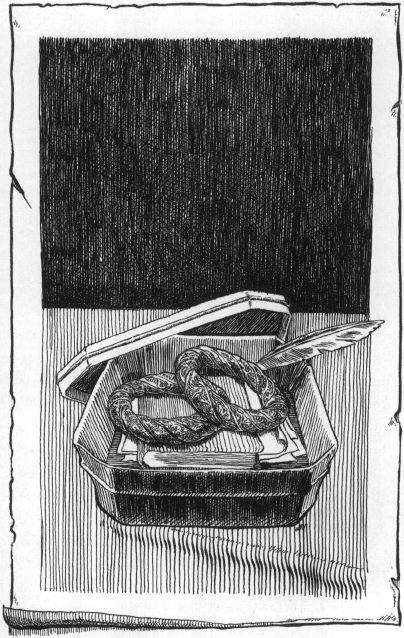

with her usual air of authority, had assured me that two members of Parliament had been found dead in a basket of snakes,

and that the Captain of an East Indiaman had been sentenced to hang from his own mast for the murder of the bosun, who was

actually a policeman in disguise.

At work, we were printing any number of news sheets describing the crimes, each of them vying to outsell the others by including

more garish and fanciful details; but needless to say none of them seemed to help explain exactly what it was we’d been caught

up in, this past couple of weeks. It didn’t take long for word to get around that I had been involved in it all: some versions

of the story evidently had me as the hero of the entire episode, judging by the people who stopped by the shop and congratulated

me in the first few days. To begin with, I tried to protest.

“I really didn’t do anything,” I told them. “I didn’t catch anybody. I don’t even really know what was happening.” But nobody

seemed to believe me, and they pinched my cheek and shook my hand with admiration despite my denials. So in the end I gave

up protesting, and just accepted the praise.

“It was a mixture of luck and — well, kind of spying,” I started telling people, bashfully, as they gazed at me with new respect.

“But I had a bit of help — here and there.”

After a few days it was impossible to go anywhere without hearing people talking about the printer’s devil who’d foiled a

whole gang of villains single-handedly, and I was feeling so important I had almost started to believe it.

“Well I must admit, if I hadn’t been there to witness

Coben and Jiggs up to no good at the docks, they’d all have gotten away with it,” I boasted. “And they didn’t bargain for

me spying on Fellman when they were laying their wicked plans. Of course, I can’t say too much about it, because Bow Street

has sworn me to secrecy on some matters.”

All this celebrity meant that I had very little time to myself for the first few days after it all happened, and I hadn’t

had a spare moment to go and see Nick.

Actually, that’s what I told myself; but the real truth was, I was terrified of going. The last time I’d seen him, he’d been

furious with me. He’d shouted, and behaved in a way I didn’t know how to explain. After we’d found the bosun’s dead body in

the Thames, Cricklebone had sent me home; and I’d left them on the dockside, Nick looking tiny and shaken, with Cricklebone’s

arm around his shoulders. I was convinced Nick would simply never want to see me again; that he’d blame me for everything.

Despite all my public bravado, I secretly wished that I’d never gotten involved in the first place, that I hadn’t been so

nosy, and most of all that I hadn’t dragged Nick into it. We’d been through so much; and something had happened, during that

last awful night, to bring us together in a way neither of us could yet quite explain. But I was too scared to confront it,

and I was avoiding him.

It must have been almost a week afterwards, and

Cramplock had sent me out on my usual errand, delivering things for his customers: a canvas bag loaded with pamphlets, letters,

bills. I’d finished the deliveries, and was scuttling back toward Cramplock’s with the empty bag over my head to keep out

the worst of the rain. Just as I was within sight of the shop, and was calling out to Lash, who was jumping into puddles with

the delight of a small child, I literally bumped into Nick on the street corner, looking utterly bedraggled.

At first we didn’t say anything. I was embarrassed. Suddenly, momentarily, the events of last week seemed like another life.

We stood there, getting wet. It was as though we were looking at one another for the first time.

Then Nick said:

“I thought I’d come and find you.”

“I’m sorry I haven’t been,” I managed to say. “We’ve —“ I was about to say we’d been busy in the shop, and then I realized

how pathetic it sounded, so I shut up.

Lash came running back when he realized Nick was there, and dug his sopping wet friendly muzzle into Nick’s palm.

“Are you all right?” Nick said, half to me and half to Lash.

“We’re fine,” I said. “Are you?”

He looked up. “I thought you’d abandoned me,” he said quietly, his face streaming with rain.

Lion’s Mane Court had been overrun by officers, looking for evidence and information, stopping everyone who tried to call,

taking things away. One of the things they’d taken away, mercifully, was Mrs. Muggerage, who had been arrested and charged

with receiving stolen goods, while investigations continued into how much of a part she’d played in the bosun’s various other

crimes. Nobody had shown much concern for Nick, and he’d been living at Spintwice’s. He was terrified that if Mrs. Muggerage

were freed, he’d have to go back and live with her; in the meantime he was trying not to think about it.

Cramplock was obviously taken aback when I appeared at the door with Nick by my side; but his immediate thought was to help

us dry off. In a flutter of kindness, he hustled us in front of the fire in the back room, produced a pile of slightly tattered

towels from somewhere, and even poured us hot milky drinks from a newly boiled pan. Lash settled down by the grate and busied

himself licking the rainwater out of his fur.

I wrapped one of the towels around my shoulders, and Nick took off his sodden, ragged shirt and laid it across the back of

a chair near the fire. Only when we’d gone some way to drying our clothes and flattened hair, and the fire was making our

cheeks glow, did Cramplock give voice to his initial surprise.

“You know, when you turned up at the door just now I could have sworn I was seeing double,” he said. “Has

anybody ever told you two boys that you’re — that you — why, you could be mistaken for one another.”

Nick shot me a significant glance and I just said:

“One or two people

have

noticed, Mr. Cramplock, yes.”

He left us, and went through into the shop; and Nick and I began to try and piece together the events of the last few days.

Even though we’d been a part of it, we were no more certain than anyone else as to exactly what had been happening. We hadn’t

seen Cricklebone, or anyone else who could tell us what was going on, since that morning on the dockside. The more we tried

to explain, the more elements there seemed to be which didn’t fit, or didn’t make sense.

The chief villain, it was clear, was the man called His Lordship. He had plainly been using his influence over people such

as Follyfeather, in the Custom House, to profit from the smuggling of goods into London. He appeared to have a whole network

of thieves operating on his behalf, all of them working for his benefit while seemingly working against each other. People

like Flethick and his friends were obviously prepared to pay a lot of money for the powder which they burned and smoked at

their strange nighttime gatherings. In turn, they made a tidy profit by selling it to other people.