Prisoner of the Vatican (34 page)

Read Prisoner of the Vatican Online

Authors: David I. Kertzer

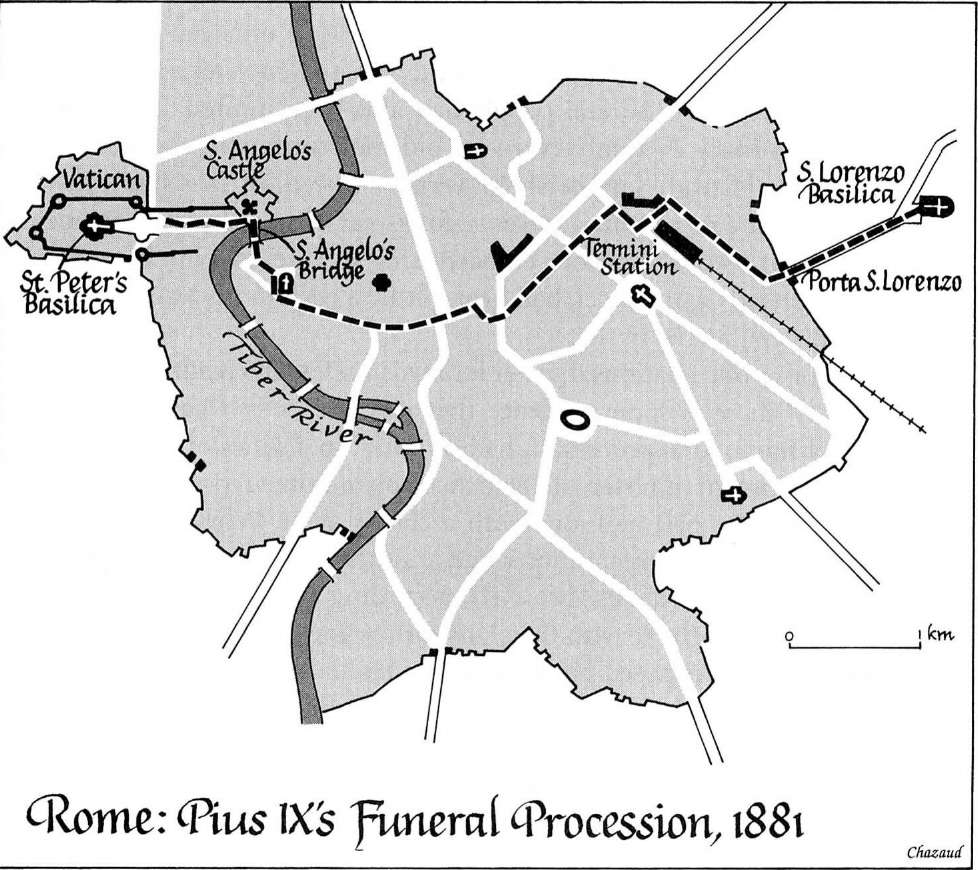

Despite receiving this warning, on the morning of the twelfth the prefect did not seem to fully register the magnitude of what was about to take place, for he wrote that "all ought to proceed in a totally private manner." Yet, while not entirely aware of just how explosive the situation was, the prefect stressed to Bacco the need to ensure that nothing disturb the procession. "I especially urge you to see that at both the Vatican basilica and at San Lorenzo there is a highly alert and sizable contingent of oversight and that this also extends along all of the roads through which the cortege will pass and is in a position to be able, in any eventuality and at any point of the route, to take prudent action to prevent or immediately stop even the smallest disorder." Should Bacco believe that the police under his command were insufficient to guarantee that there would be no public disturbance of any kind, the prefect wrote, he should let him know so that arrangements could be made to call up the troops.

Clearly nervous, Bacco made one last trip to the Ministry of the Interior, where, according to his own later account, he received some good news. The secretary-general and the Rome police chief told him that they had received new information assuring them that, despite the earlier threats by anticlerical groups, there would be no disorders. But, still uneasy, at 2:10

P.M.

Bacco sent a new telegram to the prefect, taking up his offer and asking that nine military squadrons of a hundred men each be placed at strategic points along the planned route. As soon as he received the request, the prefect sent urgent orders to the commander of the Military Division of Rome to furnish the troops. He then contacted Rome's mayor and asked him to have all available municipal police on hand to help. He also made arrangements with the Vatican's lay emissary, Vespignani, so that only those on a list that he provided would be allowed to enter the church of San Lorenzo with the pope's casket.

6

Until the morning of the twelfth, the route of the procession had been kept secret, but that morning news of it spread through the city, in the words of

Civiltà Cattolica,

"with the speed of light." As the journal put it, "Everyone's hearts were beating loudly, they could barely wait, so universal was the desire to accompany the venerated body to San Lorenzo." And although Leo had wanted to avoid a large demonstration, by the morning of the twelfth Catholic groups were distributing printed invitations calling on all good Catholics in Rome to show their respect for the dead pontiff by joining the cortege.

All day long itinerant vendors crowded St. Peter's Square, doing a brisk business in candles and torches. By shortly after eleven, in the estimation of the Jesuit journal, at least one hundred thousand people had crowded into the area between the steps of St. Peter's and the bridge in front of Sant'Angelo Castle. While this number seems suspiciously large, there is no question that the small ceremony had turned into something much different. Whatever the total number, not all were there out of devotion to Pius. Some were simply curious and wanted to see the strange and unusual event, or perhaps they knew of the battle to come and did not want to miss it. Others had a more mischievous intent.

7

At nine o'clock, inside St. Peter's, in the mausoleum beneath the main floor, the wall covering Pius IX's temporary resting place was demolished. Attendants struggled to extract the heavy bier, made of lead, and the prelates checked to see that the seals were intact.

With the funeral bier scheduled to appear from the left door of St. Peter's, about three thousand members of Rome's Catholic lay associations, bearing torches and candles, formed two lines stretching from the door down the steps. As midnight struck, the prelates with the pope's bier stepped out of the basilica and walked down the steps between the lines of the faithful. They placed the bier in the waiting wagon, covering it with a red cloth bearing the pontifical insignia. Flares shot into the sky, signaling the procession to begin. Two pairs of black horses pulled the huge wagon, the front horses each carrying a black-suited rider wearing a pointed hat.

Giuseppe Manfroni described his feelings of helplessness: "St. Peter's Square was packed, and the police (a hundred men in all)âsubmerged in a vast sea of peopleâwere impotent." The carriage carrying the pope's body, with four official Vatican carriages behind it, was followed by two hundred carriages of the Catholic faithful and three thousand candle-bearing marchers chanting prayers in Latin and Italian and reciting the rosary. But the procession had no sooner left St. Peter's Square than anticlerics began to drown out the mourners' prayers with shouts and songs. At Sant'Angelo bridge, fears mounted that the assailants might succeed in tossing the papal bier into the Tiber, with two to three hundred anticlerics bellowing, "Into the river! Into the river!"

8

The police desperately tried to separate the anticlerics from the processioners, but, as Bacco reported in a telegram sent to the prefect, "it was not possible because they were all mixed in among the carriages and the crowd."

A police captain described the scene as the procession reached the other side of the river: "The demonstrators became much more aggressive, one heard loud whistles, hostile shouts against the priests, and all of a sudden almost everybody was swept up into the demonstration, people taking one side or the other, not only in the street but from the adjoining houses as well." The police did their best to keep the protesters away from the procession once it reached the other bank, but by Piazza Pasquino what had already become unruly and embarrassing turned into something much more dangerous. In Questore Bacco's words, "The shouts on the one side and on the other were growing louder and ever more threatening. The horses of one carriage reared up in fear, and in that narrow piazza, packed with people, there was great confusion." Meanwhile, all along the way, many homesâjust how many was part of the polemics that would followâhad placed special lights and decorations outside their windows to mark the occasion, and from some of them people tossed flowers onto the funeral bier. But the lanterns perched on the windowsills were tempting targets for the protesters, whose well-aimed rocks showered shards of glass onto the street. Outside the palaces of those noblemen who lived on the route, servants bearing torches and dressed in their most formal livery had been instructed to form a line to pay their respects. They too faced jeers and worse.

The police tried to summon the military squads that had been placed in reserve along the route, but so great was the crush of the crowd that they could not get through. Near Piazza del Gesù, faced by an angry crowd, a panicked municipal guardsman unsheathed his sword, provoking shouts of outrage. His horrified captain rushed in and pulled him away.

The procession soon reached Piazza Termini, where the protesters began hacking away at a pontifical crest that a devout storekeeper had placed over his shop. When police intervened, the violence grew worse. Rocks rained on the carriages of the funeral procession, and angry demonstrators shouted, "Death to the priests!" Two military squads finally succeeded in entering the piazza and separating the protesters from the funeral cortege. But with the protesters rushing through side streets to try to reassemble farther down the route, the police urged the funeral wagons to hasten their pace, leaving many of the faithful, now disorganized and the target of hostile whistles and shouts, straggling well behind in the last stretch leading to San Lorenzo. By 3

A.M.,

the wagon with Pius IX's remains, accompanied by the carriages of the Vatican dignitaries, entered the piazza outside San Lorenzo, where another group of demonstrators waited. The police, in considerable force, were ready and succeeded in keeping them away from the cortege and the church door.

There were many arrests, not all of them among the anticlerics. In fact, the first person listed in the original report of the commander of the carabinieri was Giuseppe Riedi, age fifty-seven, a pensioner of the pontifical state living near the Vatican. Described as part of the

"clerical party," he was charged with refusing to obey police orders. But most of those arrested were anticlericals, and almost all were young men. They included an eighteen-year-old butcher, a twenty-year-old baker, an eighteen-year-old goldsmith, a nineteen-year-old hairdresser, a twenty-two-year-old clerk, and a twenty-nine-year-old municipal employee. Several people had also been injured, although none too seriously. A twenty-two-year-old cook for the priest who ran the Church's institute for Jewish converts had been hit by a blunt instrument near San Lorenzo; a twenty-four-year-old university student had been hit by a club. More embarrassing for the government, the pope's nephew, Count Pecci, had been hit by a rock in his wagon and, bloodied, been forced to flee.

9

A major public relations disaster loomed, as Depretis realized before the dawn. There is some evidence that this is exactly what those in charge of the funeral procession had in mind. In a series of reports to the British foreign minister, the British envoy in Rome reported on two conversations he had had, one with a canon of St. Peter's, who had been involved in the preparations, and another with one of the Curia's most influential cardinals. Leo XIII, according to both sources, had never been comfortable with the plans for the cortege and "highly disapproved of the proposed proceeding. His Holiness foresaw the consequences which probably would, and actually did, result from it. His Holiness never sanctioned itâbut was silent." It was the Catholic clubs of Rome that had organized the marchers bearing torches. "The effect of the clubs was to create a political demonstration, which they knew beforehand would be a provocation of the national feeling, and would probably give rise to scenes which would enable them to proclaim that there was no security for religion, or for the Church, in Rome." It had all been the work of the intransigents, the

zelanti,

and, the envoy added, "they had only too well succeeded in their purpose."

10

On the government's side, those most directly involved each tried to blame someone else. At 5

A.M.,

Bacco sent the prefect a long telegram describing the mayhem but trying to play it down, stressing that the only known injuries were to "a priest and another person, both hit by rocks, and a young woman who received a blow with a lit torch," adding that their injuries were all minor. Receiving the telegram a half-hour later and by now realizing the gravity of what had just taken place, the prefect hastened to send the telegram on to Depretis, along with a note: "From this brief report it appears that some very serious things happened that would not have happened if greater precautions had been taken. Either my orders were not precise enough, or they were not fully followed. Given what has happened, I would like Your Eminence to order a rigorous inquest."

11

Depretis was feeling great pressure. That same day two senators interrogated him on the Senate floor. The first to speak was Senator Carlo Alfieri.

"I believe that I express my colleagues' unanimous feelings," he said, "in deploring in the strongest terms the fact that, in the Kingdom's capital, a funeral cortege was unable to proceed in perfect tranquility and perfect decorum. Considering moreover that this funeral convoy was for a person who was not only of the highest status, but of such high virtue, worthy of respect and veneration even by those having very different opinions and convictions from those of the illustrious Pontiff, the deplorable events of last night assume even greater gravity." Senator Cambray-Digny then followed, seconding Alfieri's comments and asking Depretis "how was it that, knowing how important it was that this cortege proceed solemnly, the necessary precautions were not taken to effectively prevent the disorders that were all too easy to foresee?"

The prime minister rose to reply. "I too," he said, "hasten to say that I deplore the painful events that took place last night no less than the senators who have spoken." But Depretis tried to minimize the commotion and to cast the blame elsewhere: "During the funeral cortege a few irresponsible people disturbed the holy ceremony. But nothing serious occurred. The authorities intervened and enforced respect for the law. Despite this, some disorders did take place which, especially in the capital of the Kingdom, under the very eyes of the Government, ought not to have occurred." Depretis went on to explain how this had happened.

The government had been informed of Pius's funeral wishes, Depretis recalled. "Yet only yesterday the Government learned that invitations were being sent to the faithful to encourage them to take part in the holy service. The Government made the necessary arrangements, but in a stretch of road such as that running from St. Peter's all through the city to the church of San Lorenzo outside the opposite wall, it was impossible to prevent disorders at all points along the way."

Just who was responsible, Depretis went on to say, remained unclear. He had ordered an inquiry to find out and to determine whether any of the public security forces had failed to carry out their explicit instructions to maintain order. Should the latter prove to be the case, he pledged, appropriate punishment would be meted out.

12