Prisoner of the Vatican (36 page)

Read Prisoner of the Vatican Online

Authors: David I. Kertzer

"Every people has its role in history," Mario proclaimed. "Italy's is to suppress the papacy and with the abolition of the guarantees we will reach this goal."

Mario then turned to the pope's threats to leave Italy: "Have you read the allocution Signor Pecci gave yesterday? It appears that he is considering fleeing." To this the audience responded with laughter, sharp whistles, and shouts of "Would that it were so! Into the river!" Mario continued: '"To the enemy who flees, a golden bridge,' goes the saying, and if he would only let us know the day he is leaving Rome, all of Rome would be there to wish him a pleasant journey." A sea of "Yes! Yes!" drowned out his next words.

Mario reminded the crowd of the polemics over Pius IX's funeral procession. "The pope has told a lie," he said. A voice called out, sarcastically, "But the pope is infallible!" "He is an infallible liar," replied Mario, to the crowd's delight. "Signor Pecci has said that a few of the faithful, praying, accompanied Pius IX's body. And herein is the lie. It was the clerical party, who took advantage of the opportunity of transporting Pius IX's body to mount a demonstration hostile to Italy. But in illuminating the carcass of Pius IX, they shed light on the whole history of this despicable pontiff."

27

Adriano Lemmi, long a friend and financial supporter of Mazzini's and soon to become national head of the Italian Freemasons, followed Mario to the podium. Lemmi began to read the resolution that was to be voted on. It began with a preamble: "Considering that the papacy and Italian unity are mutually contradictory historically and politicallyâthe popes called in foreign forces 35 timesâ" Here Lemmi was interrupted by a loud, angry shout: "Assassins!" And considering, he continued, that the papacy undermined national sovereignty, "the people of Rome want that law [of guarantees] abolished and the Apostolic palaces occupied."

But in calling for the taking of the Vatican, Lemmi had gone too far. A police official who, with a cadre of officers, had been monitoring the meeting, rose and tried to silence him. Pandemonium followed. "Long live the Inquisition," one outraged anticleric shouted; others whistled. Petroni got up and tried to restore order, but his voice could not be heard over the din. Ricciotti Garibaldi stood on two chairs and tried to get people's attention but failed. Finally, one of the meeting's less illustrious leaders, who, however, surpassed his comrades in vocal volume, cried out. He recited the rest of the proposed motion and concluded by putting the question simply: "Do you want the abolition of the guarantees and the occupation of the Apostolic palaces?" A storm of applause and whistles of approval were only partially drowned out by the efforts of the police to clear the room. A squad of police reinforcements arrived, and by noon the Politeama was empty

The next day, the newspapers that published the rally's speeches were confiscated by the police. Among the offices raided were those of the Vatican's

Osservatore Romano,

for its edition had contained excerptsâwith suitable outraged commentaryâfrom the speeches. And so, much to his consternation, the director of the Vatican daily found himself condemned by court order for having violated article 2 of the law of guarantees: he stood charged of offending the pope.

28

I

N THE WAKE OF THE EVENTS

of July 12â13, the Vatican ratcheted up its stark imagery of a besieged Church battling the forces of evil. Typical was

Civiltà Cattolica's

language: "There are two Romes: one pagan or, more precisely, apostate, the other Christian; the one that oppresses, the other that is oppressed, the one composed almost wholly of foreigners, the other composed of the descendants of the true Romans." While pagan Rome "has its parliamentarians, its laws, and its materialist, atheist schools, Christian Rome has as its head Peter's successor, who since 1870 has been a prisoner in the Vatican ... For more than a decade these two Romes have stared each other in the face. The one curses the Pontiff, the other goes reverently to kiss his feet; the one insults, the other weeps and prays."

1

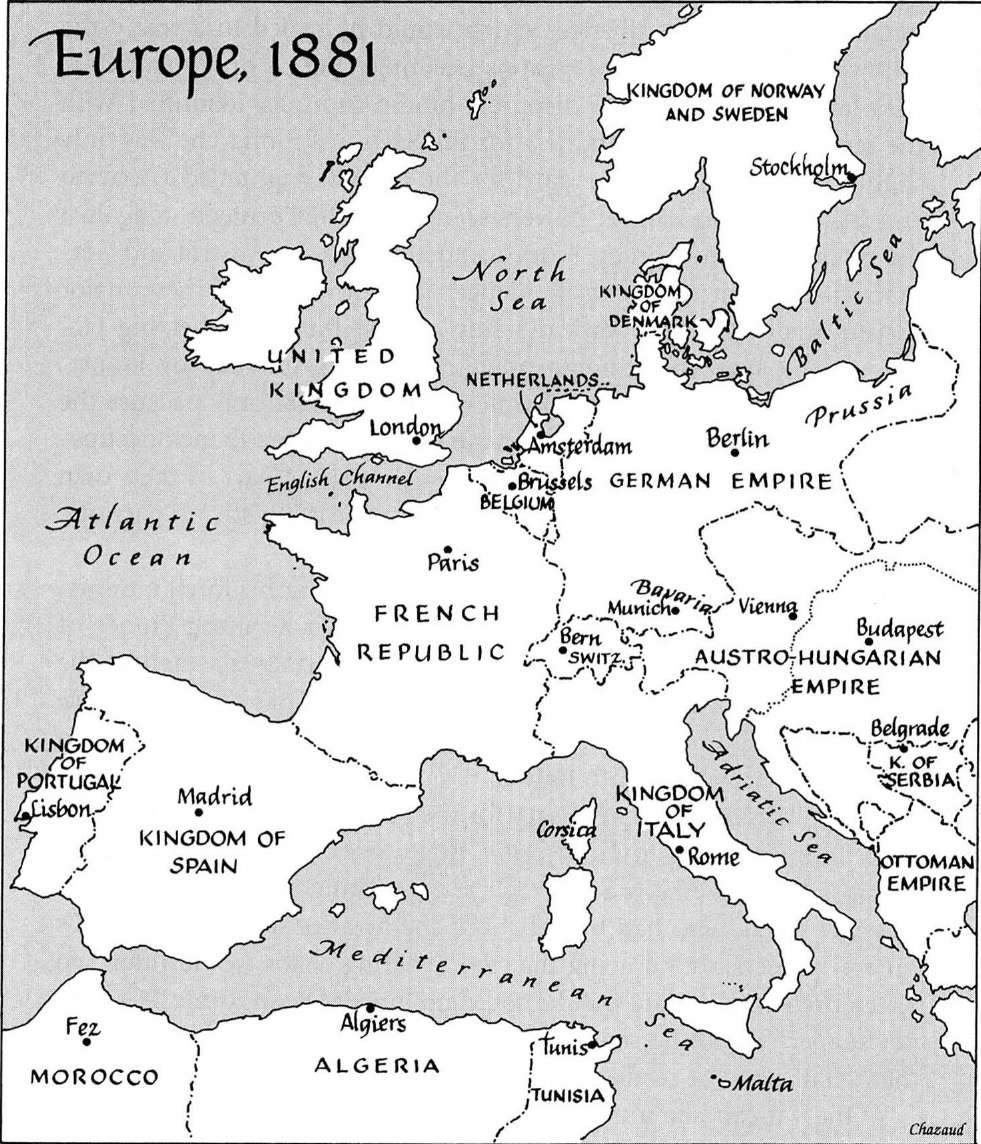

Just where the battle between the anticlerics and the Church would lead was not clear. On August 17,1881, the British envoy, reporting from Rome, wrote ominously to the foreign minister in London: "I regret to inform your Lordship that, whether with or without the connivance of the authorities, the quarrel between Papists and anti-Papists is daily assuming more important dimensions, and, if allowed to continue, may lead to consequences far more serious than the Italian government appears to have the necessary sense to foresee." Rumors of the pope's impending departure had again begun to spread, although in the envoy's view, Leo had little desire to leave, and the Italian government had every interest in his staying. Only should things get worse, he reported, would the pope flee, his likely destination being Austria.

2

In preparing the circular to the nuncios on the papal funeral procession in late July, the pope had consulted with the cardinals of the Congregation of Extraordinary Ecclesiastical Affairs, and they again raised the question of departing from Rome. Cardinal Camillo Di Pietro, arguing that it was futile to send out yet more protests against the sorry situation to which the Holy See had been reduced, suggested that the pope immediately seek asylum in another country The cardinals were divided about the wisdom of such a move, but they urged that the possibility of flight be further explored and debated whether it would be helpful for the pope to use the threat of departure in his upcoming allocution.

3

In the end, the circular included just such a threat.

Following the instructions in the circular, the papal nuncio in Vienna met with Austria's assistant foreign minister. Impatient with the minister's generic expressions of sympathy, the nuncio invoked the specter of papal flight. As he recounted in his report to Jacobini: "I could not help but add that the future looked rather bleak, and if things continued to go the way it looked like they were heading following the important events of July 13, it was not unlikely that considerations of his own dignity and security would prompt the Holy Father to leave Rome."

The Austrian official was not impressed. "Ah! No!" he replied. "We hope that such an eventuality will not come to pass and that such deplorable events as occurred on July 13 will never be repeated."

4

The pope's supposed plans to leave Italy quickly became the subject of animated discussion in the press, a weapon used by all sides. On August 10, just three days after the Politeama protest meeting, the Roman daily newspaper

II Diritto,

widely viewed as the unofficial mouthpiece of Depretis himself, reported that Leo had in fact made the fateful decision to leave Rome. The pope, the long article continued, had made up his mind shortly after the funeral procession disorders and had communicated it to a number of foreign powers. Leo had also decided where he would goâto Malta. The cardinals, who were consulted on the matter, were in full accord. "Political circumstances may speed up or delay his departure,"

II Diritto

related, "but it seems that it is unlikely that they will prevent it."

The Vatican press was not denying these rumors. On August 10, the French Catholic news agency, Havas, angered the Vatican by reporting that the pope had decided to stay in Rome. In recent days, the agency claimed, "the pope has declared to many members in his retinue that he is resolved not to abandon Rome unless made to do so by force. Instructions have been sent to the nuncios telling them to reply in this fashion if they are asked."

L'Osservatore Romano

dismissed the story curtly: "We are in a position to state that the whole content of this article is pure invention." But in the wake of the funeral disaster, the Vatican paper itself was brandishing the threat of papal departure, observing: "History teaches us that every time that the pope, forced by the tyranny of either the plebes or governments, left Rome defeated and humiliated, he returned there triumphant and covered with glory."

5

Although the Italians were then accusing the French of plotting the pope's departure as part of their efforts to weaken the Italian state, French diplomatic correspondence makes it clear that such charges were groundless. In response to the new wave of stories about the pope's leaving Rome, the French foreign minister sent instructions on August 14 to his envoy to the Holy See. "The pope's abandonment of the traditional seat of the papacy would have the most unfortunate consequences," he wrote. "His departure from Rome would become the signal for a popular uprising against Catholic institutions in Italy which the royal government would most likely be unable to quell. This revolutionary movement would be very dangerous for Italy itself without thereby benefitting the papal cause. It is impossible in any case to predict how long the agitation that would follow might last, what course it would take, and how long the period of exile would be to which the papacy would have condemned itself." The foreign minister also worried about the impact that the pope's departure would have elsewhere in Europe, for Catholic sentiment would everywhere be inflamed. He concluded by telling his envoy to convey these thoughtsâunofficiallyâboth to the pope and to the cardinals he knew.

6

In fact, unknown to most Italians, their government was then in the early stages of forming a Triple Alliance, aligning with Germany and Austria, aimed in good part against France. This action was in some ways unexpected, for it was France that had helped the Savoyard monarchy unite Italy by fighting against Austria, the main foreign foe of unification. That it was a government of the left that engineered the alliance against the French also had much to say about the abandonment by men like Depretis, Crispi, and Mancini of their old republican principles, for they were now taking the side of a German king and an Austrian emperor against republican France.

But various developments in 1881 helped push the Italian government into the Triple Alliance, which would be sealed in a treaty the following year, its secret provisions becoming public only many decades later. The anticlerical disorders of the summer, identified with the republicans, whose fondness for the Savoyard monarchy was only slightly greater than their regard for the papacy, frightened Umberto and his court. The central powers seemed to offer protection against the threat to the monarchy. Forming an alliance with Austria and Germany also meant removing the danger that either one of these major powers might take the Vatican's side against Italy. Another big factor was the aggressive foreign policy then being pursued by France. Depretis himself had become prime minister in 1881 only because the previous government had fallen in the spring after the French occupation of Tunisia, which Italians viewed as properly a part of their own sphere of influence. In this atmosphere, it was easy to stir up patriotic sentiment against the French.

7

On August 15, the French ambassador to Italy sent his foreign minister copies of two recent Italian newspaper stories accusing France of plotting with the pope against Italy. He was especially alarmed by the piece in

La Riforma,

a paper viewed as under Crispi's control. France was planning a war against Italy, the paper reported, and was preparing "to lead the pope back into Italy in the midst of the French army!" Of course, it would first be necessary for the French to get the pope out of Italy, and, according to

La Riforma,

this was exactly what the French ambassador to the Holy See was secretly working to do. It was he, the paper charged, who had been behind the arrangements for Pius IX's funeral procession, knowing that the resulting chaos would offer Leo XIII a pretext to declare that he could no longer live in Rome. "Crispi's newspaper," the ambassador reported, "ended its article by asking that the Italian army be readied."

8

At the Vatican, the summer's events had left everyone on edge. Eager to demonstrate that most Italians were on the pope's side, various Catholic associations organized pilgrimages to the Vatican, an effort that continued throughout the next decade. The tension was palpable. A secret police report told that, following the disorders, "the wall near the Vatican gardens was being guarded for fear that it would be

climbed and a sudden assault made without the Government's knowledge." It concluded: "In the Vatican they fear that the republican and socialist party have already infiltrated the army and the civil authority itself... they do not believe that even the Savoyard dynasty is safe."

9

It was a dangerous moment for the papacy, for the new Italian state, and for much of Europe. Italy was in an uproar about the French invasion of "its" Tunisian territories, and murmurs of war with France were growing ever louder. Although to this point the French had been working behind the scenes to calm the Vatican waters, they now began to see some advantage in roiling them. On Monday, October 17, the French chargé d'affaires in Rome, the marquis de Reverseaux, reported just how tense the city was. The previous day, the pope had received a large number of Italian pilgrims in St. Peter's. The Italian authorities were worried that anticlerics might infiltrate the ceremonies, and for good reason. "Just one shout hostile to the Holy Father," the envoy wrote, "could have led to a clash in the church itself whose consequences would likely have been the pope's departure from Rome."