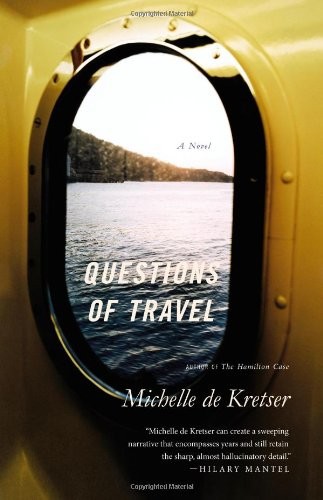

Questions of Travel

In accordance with the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, the scanning, uploading, and electronic sharing of any part of this book without the permission of the publisher constitute unlawful piracy and theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), prior written permission must be obtained by contacting the publisher at [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights.

IN MEMORY OF LEAH AKIE

Under cosmopolitanism, if it comes, we shall receive no help from the earth. Trees and meadows and mountains will only be a spectacle…

E. M. Forster,

Howards End

But surely it would have been a pity

not to have seen the trees along this road,

really exaggerated in their beauty

Elizabeth Bishop,

“Questions of Travel”

Title Page

Welcome Page

Dedication

Epigraph

I

Laura, 1960s

Laura, 1970s

Ravi, 1970s

Laura, 1970s

Ravi, 1970s

Laura, 1980s

Ravi, 1980s

Laura, 1980s

Ravi, 1980s

Laura, 1980s

Laura, 1980s

Ravi, 1980s

Laura, 1980s

Laura, 1980s

Laura, 1980s

Laura, 1980s

Ravi, 1980s

Laura, 1990s

Ravi, 1990s

Laura, 1990s

Ravi, 1990s

Laura, 1990s

Ravi, 1990s

Laura, 1990s

Ravi, 1990s

Laura, 1990s

Ravi, 1990s

Laura, 1990s

Ravi, 1990s

Ravi, 1990s

Ravi, 1990s

Laura, 1990s

Ravi, 1990s

Laura, 1990s

Laura, 1990s

Ravi, 1990s

Laura, 1990s

Ravi, 1990s

Laura, 1990s

Ravi, 2000

Ravi, 2000

Laura, 1999–2000

Ravi, 2000

Laura, 2000

Ravi, 2000

Ravi, 2000

Laura, 2000

Ravi, 2000

II

Laura, 2000

Ravi, 2000–2001

Laura, 2000–2001

Ravi, 2001

Laura, 2001

Ravi, 2001

Ravi, 2001

Ravi, 2001

Laura, 2001

Laura, 2001

Laura, 2002

Ravi, 2002

Laura, 2002

Ravi, 2002

Laura, 2002

Ravi, 2003

Laura, 2003

Ravi, 2003

Laura, 2003

Ravi, 2003

Laura, 2003

Laura, 2003

Ravi, 2003

Laura, 2003

Ravi, 2003

Ravi, 2003

Laura, 2003

Ravi, 2004

Laura, 2004

Ravi, 2004

Ravi, 2004

Laura, 2004

Ravi, 2004

Laura, 2004

Ravi, 2004

Laura, 2004

Ravi, 2004

Laura, 2004

Ravi, 2004

Ravi, 2004

Laura, 2004

Laura, 2004

Ravi, 2004

Laura, 2004

Ravi, 2004

Laura, 2004

Credits

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by Michelle de Kretser

Newsletters

Copyright Page

Anywhere! Anywhere!

Charles Baudelaire,

“Anywhere Out of the World”

WHEN LAURA WAS TWO,

the twins decided to kill her.

They were eight when she was born. Twenty-three months later, their mother died. Their father’s aunt Hester, spry and recently back in Sydney after half a lifetime in London, came to look after the children until a suitable arrangement could be made. She stayed until Laura left school.

Look at it from the boys’ point of view: their sister arrived, they stood by their mother’s chair and watched an alien, encircled by her arms, fasten itself to her nipple. Their mother didn’t die at once but she was never well again.

Breast cancer.

They were clever children, they made the connection. In their tent under the jacaranda, they put together a plan.

Once or twice a year, as long as she lived, Laura Fraser had the water dream. There was silky blue all around her, pale blue overhead; she glided through silence blotched with gold. Separate things ran together and were one thing. She was held and set free. It was the most wonderful dream. But on waking, Laura was always a little sad, too, prey to the sense of something ending before its time.

She had no recollection of how it had gone on that Saturday morning in 1966, her brothers out in the street with bat and ball, and Hester, who had switched off her radio just in time, summoned by a splash. No one could say how the safety catch on the swimming-pool gate had come undone; the twins, questioned, had blank, golden faces. Next door’s retriever was finally deemed responsible, since a culprit, however improbable, had to be found.

To the unfolding of these events, the boys brought the quizzical detachment of a general outmaneuvered in a skirmish. It was always instructive to see how things went. They were only children, ingenious and limited. They had no real appreciation of consequences or the relative weight of decisions. If Laura had owned a kitten, they might have drowned that instead.

The pool was filled in. For that, too, the twins blamed their sister. Their mother had taught them to swim in that pool. They could remember water beaded on her arms, the scuttle of light over turquoise tiles.

L

ONG-FACED AND AMBER-EYED,

what Hester brought to mind was a benevolent goat. She had spent the first seven years of her life in India, from which misfortune her complexion, lightly polished beech, never recovered.

Every night, Laura listened while Hester read about a magic land called Narnia. By day, the child visited bedrooms. They contained only built-in robes—a profound unfairness. Still she slid open each door. Still she dreamed and hoped.

Glamour, on the other hand, was easily located. It emanated from the sky-blue travel case in which Hester kept her souvenirs of the Continent. There was a tiny Spanish doll with a lace mantilla and a gilded fan. There was a program from

Le lac des cygnes

at the Paris Opéra, and a ticket from the train that had carried Hester over the Alps. Dijon was a

menu gastronomique,

Venice a sea-green, gold-flecked bead. An envelope held postcards of the Nativity and the Fall as depicted by Old Masters, and tucked between these arrivals and expulsions, a snapshot of Hester overexposed in white-framed dark glasses against the Greek trinity of sea, sunlight and symmetrical stone.

Laura would beg for the stories attached to these marvels. Because otherwise they merely thrilled—they were only crystals of Aeroplane Jelly: ruby red, licked from the palm, briefly sweet. Hester saw a small, plain face that pleaded and couldn’t be refused. But the tales she offered it disturbed her.

As a young woman, she had settled in London. There, stenographically efficient in dove-hued blouses, she survived a firm of solicitors, a theatrical agency and two wartime ministries. Then she turned forty and went to work for a man named Nunn. On the occasion of the Coronation, Nunn smoothed his moustache, offered Hester a glass of sherry and promised her

tremendous times.

Hester expended three pages on this in her diary but not a word on the practical arrangement at which she had arrived with the mathematician from Madras who rented the flat below hers. Novelties to which he introduced her included cheating at bridge and a sour fish soup.

In Hester’s girlhood it had been hinted that France was a depraved sort of place, so naturally it was to Paris that her thoughts turned when she realized, as her third Christmas in his office approached, that she was in love with Nunn. Hester imagined him making her his mistress in a room with a view of the Eiffel Tower—she imagined it at length. An accordionist played “Under the Bridges of Paris” beneath their window; Nunn threw a pillow at him. Food was still rationed in England, so Nunn gave orders for tender steaks and velvety puddings to be placed under silver covers and left at their door. Their bed was draped in mauve silk—no, a deep, rich red. When Hester learned that her employer intended to spend the holidays with his wife’s parents in Hull, she crossed the Channel anyway. Nunn might detect traces of French wickedness about her when she returned and be moved to act.

Paris, in those years still trying to crawl out from under the war, was morose and inadequately heated—scarcely different, in fact, from London. But a precedent had been set. Every year, Hester penny-pinched and went without so that she might go on spending her holidays abroad. Partly it was the enduring hope that she might yet return with something—an anecdote, a daring way with a scarf—that would draw her to Nunn’s attention

in that way

at last. Partly, and increasingly as time passed, it was the dismay that pierced her at the prospect of solitary days spent in London with neither companion nor occupation (for her arrangement with the mathematician was confined to alternate Wednesdays).

When Nunn’s wife finally came to her senses and died, he promptly married her nurse. Hester realized that she was fed up with England. On the voyage home to Sydney, she stood at the ship’s rail late one night. The eleven volumes of her diary splashed one by one into Colombo Harbor.

Because all this had to be excluded from the stories laid before Laura, they suggested journeys undertaken in order to seek out delightful new places. Whereas really, thought Hester, her travels had been a kind of flight.

The way to crowd out her misgivings was to talk and talk. So it wasn’t enough to describe the dishes on the handwritten menu from Dijon: a pear tart as wide as a wheel, snails who had carried their coffins on their backs. Hester found herself including the lilies etched on the pink glass shades of the lamp on her table, and the stag’s head mounted on the wall. She described the husband and wife who, having had nothing to say to each other for forty years, inspected her throughout her meal. Where recollection had worn thin, she patched and embroidered. Laura shivered to hear of the tight little square in front of the restaurant where once the guillotine had stood: a detail Hester concocted on the spot, feeling that her narrative lacked drama and an educational aim.

So the story that made its way to Laura was always vivid, informative, and incidental to what mattered. Conjuring the glories of Athens, Hester passed over the unspeakable filth of Greek public lavatories that obscured her memory of the Acropolis, greed and incaution having led her to consume a dish of oily beans in Syntagma Square. Calling up the treasures of the Uffizi, she didn’t say that she had moved blindly from one colored rectangle to the next, picturing ways in which Nunn might compromise himself irrevocably in the filing room. Rose windows and Last Judgments dominated her description of Chartres, but when Hester had been making the rounds of that cold wonder, all her attention was concentrated on the selection of a promising effigy. Tour guides harangued, Frasers howled in their Presbyterian graves. Hester lit candles in a side chapel, knelt, offered brief, fervent prayers.

After talking about her travels, Hester was often restless. Turning the dial on her transistor late one night, she heard a woman say gravely,

Away is hard to go, but no one / Asked me to stay.