Radio Free Boston (16 page)

Authors: Carter Alan

Then there was hard rock, best exemplified by a scruffy and pimply local band named Aerosmith, which released its first album the same day Bruce Springsteen released his. “The first person ever to play our record was Maxanne, who was on '

BCN

in the afternoons,” Steven Tyler mentioned in the band's biography

Walk This Way

. Maxanne involved herself deeply with the Boston music scene, loved the hard bluesy rock of Aerosmith, and persistently championed the group to Norm Winer and the other jocks. Nevertheless, everyone missed the appeal of a band that channeled the Yardbirds, James Brown, and the Jeff Beck Group. “I refused to let Maxanne play Aerosmith in the beginning,” Winer confessed, “I thought they were too derivative. But, of course, she was right.” The program director decided to let '

BCN'S

listeners be judge and jury, and then admitted defeat when all the positive reaction on the phones just blew him away. Winer even green-lighted a live broadcast of the band from Paul's Mall on 23 April 1973. That show, which featured songs from the debut album, plus some covers, showed the

WBCN

staff what Maxanne had sensed all along: this was a terrific live act and one that the station should invest in. Some of the folkies on the air staff might not have liked Aerosmith all that much, but any group that took a serious crack at “Mother Popcorn” by James Brown had to deserve some respect.

In August 1975,

WBCN'S

first serious challenge from another radio station abruptly shouldered its way onto the

FM

radio dial. Previously known for playing innocuous elevator music,

WCOZ

began broadcasting an automated selection of album-rock favorites from The Who, the Eagles, and Rolling Stones among others. In short order, the owners at Blair Radio hired some talented radio personalities to fill out the schedule. These new challengers emulated the format and personas established by '

BCN'S

veterans, speaking conversationally and concentrating on younger lifestyle issues, but sharply

reducing the variety of the music selections played. Not unlike the

AM

Top 40 approach, though not as extreme, the station installed a format that whittled down the available library to just the most appealing tracks, as determined by requests and market research. Andy Beaubien, who would later work as a

DJ

and program director at the new station, commented about its arrival: “We didn't take '

COZ

very seriously. To be perfectly honest, we had a superior attitude, which was endemic at '

BCN

. We were kind of elitist: âThey're nothing compared to us; we're the originals, we're the best.'”

“We were certainly aware of what they were doing, but we felt it was most important to perpetuate what it was that '

BCN

represented,” Tommy Hadges observed. “Maybe we were naive in the beginning; we didn't know how much impact ['

COZ

] would eventually have in the marketplace.”

Indifference to the new challenger soon led to a grudging awareness. Almost immediately,

WCOZ

had an impact on the veteran station as listeners who might not enjoy the many colors of the musical palette suddenly had an alternative to switch to. A rock music fan who would have remained listening to

WBCN

while Old Saxophone Joe segued from the Stones into a Sonny Rollins saxophone piece could now flip the dial to find “Won't Get Fooled Again” on '

COZ

. It was such a dramatic incursion that by mid-1977,

WBCN'S

Arbitron rating stood at 1.7, while its chief tormentor had stomped to a 4.6. “The downhill thing for me was the whole '

COZ

thing and the ratings that they got,” bemoaned Al Perry. “Maybe we needed to clean up our act a little bit, but traditionally, in the history of radio it happens a lot: someone comes along, beats the big guy up for awhile, the big guy makes adjustments, stays the course and people come back.” But the general manager was constantly kept under pressure by Mitch Hastings, who, despite his frail appearance and absent-minded behavior, became surprisingly irritated and tenacious. “Mitch wasn't a stand still kind of guy. He kept saying, âThere's something wrong, there's something wrong.' I said, âWe just have to stay the course.' But, he didn't want to stay the course; he kept the pressure up until finally I said, âI can't do this, it's too much.'”

Al Perry's departure marked a sea change for

WBCN

. Then there was another serious blow: Norm Winer, who had presided over the circle of

DJS

for five years, also decided to move on. “I was personally disenchanted with some of the stuff [going on] in Boston, given the ideals of the time. The school bussing thing really disturbed me; Boston had been a horribly racist place in previous generations, and we thought we had escaped that.

My girlfriend of many years split and my home in Concord was empty with me being the only one living there. That was all part of my general disenchantment.” When Winer received an offer to replace the morning man at

KSAN-FM

in San Francisco, he pounced. But, as critical as were the double departures of Perry and Winer, fate hammered a third stake into

WBCN'S

heart in '76 when Charles Laquidara completed his final show and quietly skipped town. Particularly hard to accept, by those who knew the truth, was that the host of “The Big Mattress” was not jumping ship to another radio station but leaving to embrace the new love of his life: “I was heavily into cocaine, and the show was getting in my way,” Laquidara remembered matter-of-factly. The official excuse at the time was that the

DJ

was leaving to pursue his passion for acting full time. “Yeah, that's because I couldn't tell everyone I wanted to go off and do cocaine for the rest of my life. But, when I left, I literally told friends, âI know this [is] going to kill me, but it's such a great way to die!' That's how much I loved it.” When Laquidara came in for his last broadcast, only a few people had a clue that it was the end. He had prerecorded the last two hours of the “Mattress” the day before. “When I started the show, I announced to everybody I was leaving. I did the first couple hours live, then I started the tape, and just walked out. I was through with radio for the rest of my life, and I was on my way to Vermont.”

As Laquidara drove west on Route 2, further and further from the station that had made him famous, away from a stunned group of coworkers and thousands of surprised listeners, he focused with delight on his new, if impulsive, freedom. Seduced by the taste of a new relationship, an obsession that would most likely kill him, the ex-morning announcer bopped blissfully along, tugging on a big, fat joint and listening to the car radio the whole way out to the northern interstate, even as the fringes of static began to grow and grow. Then, as the roach cooled in the ashtray and the car whizzed past the pines along Route 91 north, no amount of fiddling with the knobs on the radio could prevent the atmospheric noise from completely crowding out any trace of 104.1 in Boston. But by that point, Laquidara wasn't even trying.

There was this shock that someone would have the nerve to try to take what we were doing and castrate it to make it more commercially viable.

JOHN BRODEY

THE

BATTLE

JOINED

It's interesting to consider that one of

WBCN'S

cornerstone talents, who would remain with the station for thirteen years, developed his Boston radio career by working to co-opt the very audience that “The American Revolution” had fostered since 1968. Ken Shelton would participate in a near-dismantling of Camelot, a surprise attack from across the radio dial that

WBCN'S

denizens, absorbed in their own greatness, would remain badly naive of until it was almost too late. As one of the standard-bearers at the upstart

WCOZ

, Ken Shelton was destined to plunder large numbers of listeners from the ranks of a station once considered bulletproof, protected by the unwavering support from its community since inception. But as the seventies passed the halfway point, '

BCN

, in a languished state with a depleted rank of veterans, found itself vulnerable to a new rival with roots in an old approach â the Top 40 system of concentrating more attention on fewer songs.

As a kid in Brooklyn, Ken Shelton grew up loving the music of Elvis Presley and the pop hits of the late fifties and early sixties, furtively listening at night to a small transistor radio hidden under his pillow. Later, he discovered and embraced the sixties counterculture, hanging out in the Village and seeing the Fugs and the Blues Project as well as the Band at the Fillmore. He graduated from college with a bachelor's in speech and theater, ostensibly for a career in television. “It was 1969; Vietnam was still going on, so the goal was to stay in school,” he remembered. “I looked around for graduate schools and ended up at

BU

.” When Shelton arrived in Boston, the first thing he did, like everybody else, was set up his stereo system. “I scanned up and down the dial and suddenly I heard âWitchi-Tai-To' by Everything Is Everything. [I] never heard that before. So, for the next two years, I did not move that radio dial from '

BCN

; I couldn't tell you the name of any other station.”

After graduation, considering Shelton's distinctive deep voice and passion for radio, it seemed a likely career choice, but marrying his college sweetheart meant that he better bring home the bacon â and quickly. Since he'd studied for a job in television, Shelton got a job at Channel 4 (

WBZ-TV

) as an assistant director, working nights, weekends, and holidays, and becoming the floor manager on Rex Trailer's

Boomtown

kids show. “Rex used to ride his horse into the studio, and one time, there was a big [accident] on camera,” Shelton recalled, pinching his nose and chuckling. “Somewhere was a pot of gold and some creativity in

TV

production, but it sure wasn't there!” Then, the restless director ran into Clark Smidt, one of his grad school buddies, who had worked his way into

WBZ'S

radio division selling ads for the

AM

station and managing the younger

FM

signal, which broadcast classical music by day and jazz at night. Shelton expressed his unhappiness, mentioning he was tired of sweeping up after . . . the talent. Smidt rapidly became Shelton's ticket, finagling his buddy into the radio division as his programming assistant.

When the parent company, Westinghouse, decided to flip

WBZ-FM

over to a contemporary Top 40 rock format, the station became an automated jukebox with Smidt and Shelton picking the songs and voice-tracking the entire broadcast day on tape. “It went on the air December 30, 1971, and the first record was

American Pie

, the long version,” Smidt recalled. “It was a tight playlist, but we did slip in a few album cuts.” The pair came up with innovative features like the “Bummer of the Week,” where listeners

suggested a song they hated, and the

DJS

would, literally, break the vinyl on the air. The format quickly generated impressive ratings, even if the company didn't want to put too much effort into it. “The general manager came in one day,” Shelton recalled, “and said, âWe don't want you guys to have too much of a presence; it's the music [that matters], so from now on, no last names on the air. You're Clark. You're Ken.' I had a little desk in Clark's office and he would call over to me, âHey Captain!' I thought that âcaptain' had a nice ring to it. They said no last names, but nothing about nicknames, so, I started using âCaptain Ken' on the air and it stuck like Krazy Glue!”

At the end of '74, Smidt and Shelton made a fervent pitch to Westinghouse for more resources, but the company balked at the idea of pumping additional dollars into

WBZ-FM

. “The head of Westinghouse thought

FM

was just a fad,” Shelton bemoaned. “Our hearts were broken. Clark didn't stay much longer, and I was only there a few months after that.” But the lessons learned in that experience proved that there was room for a station in Boston that played a mixture of rock-oriented Top 40 hits and appealing songs from

LP

s, which had become the medium of choice for much of the college-aged audience. In 1972, Blair Radio had purchased

WCOZ

, a beautiful music

FM

station with the slogan of “The Cozy Sound, 94.5 in Boston.” Three years later, “Clark got the job as program director to turn '

COZ

into a rocker and go against '

BCN

,” Shelton stated. “I was the first person he hired.”

WCOZ

switched to rock programming on 15 August 1975 and then, during the Labor Day weekend, aired a syndicated special called “Fantasy Park: A Concert of the Mind.” Smidt marveled, “What a reaction that got!” Originally produced at

KNUS-FM

in Dallas and broadcast in nearly two hundred markets, the two-day “concert” generated excitement in nearly every market it aired. Songs from existing live albums were assembled to make it appear as if all the best rock bands in the world were together on the bill of some incredible concert that was being broadcast as it happened. “It was a three-day fictional Woodstock-like event designed for radio,” said Mark Parenteau, soon to be hired by the newly minted

WCOZ

. “People weren't sure if the concert was real.” David Bieber, at the time a freelance marketing specialist, was also impressed: “It was a total cliché of radio being a theater of the mind, grabbing live album tracks and presenting this concert that had never occurred. '

COZ

just came along, taking all these marquee

names that '

BCN

had been present with during the creation of their careers, and stole the thunder.”

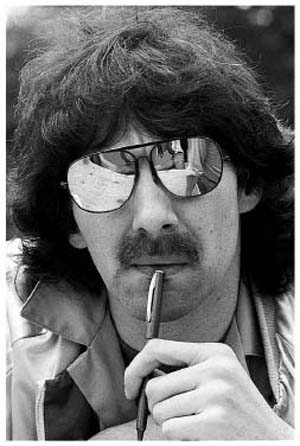

Mark Parenteau gets his break at Boston's Best Rock: 94 and a half, wCoZ. Photo by Dan Beach.

After

WCOZ'S

dramatic arrival, Clark Smidt began replacing the automated programming with live

DJS

, installing his protégé Ken Shelton in the early evening. George Taylor Morris, Lesley Palmiter, Lisa Karlin, Stephen Capen, and others were soon to follow. “Then there was Mark Parenteau,” Smidt laughed. “I remember him telling me, âI'm so broke, I've got to get hired. I had to run the tolls from Natick just to get here!'” Parenteau then suggested that Smidt hire Jerry Goodwin, one of his buddies at

WABX-FM

in Detroit, who had been a veteran announcer with his “deep pipes” at several A-list radio stations around the country. Goodwin, a native New Englander, had returned to Boston to pursue a PhD in social ethics at Boston University's School of Theology. “Mark [Parenteau] seriously hunted me down. He said, âGive up this religious zealotry you're into. Come back to where you belong!' It seemed like a good idea, so I started working for '

COZ

[as] their production director and doing weekends.”

WCOZ'S

list of album tracks and mainstream hits included songs that would become classic rock standards many years later: “The Joker” from Steve Miller, “Baba O'Riley” by The Who, Elton John's “Saturday Night's Alright for Fighting,” and “Sweet Emotion” from Aerosmith. Along with a tighter playlist, '

COZ

guaranteed fewer commercials, less talk from the

DJS

, vibrant station identifiers, and up-tempo production. Smidt called it, “Boston's Best Rock: 94 and a half,

WCOZ

.” The mix appealed to an audience that suddenly had an alternative to the only

FM

rocker in town. “The first book [ratings period], fall '75, was a legendary one,” Smidt recalled. “For

listeners twelve years and older,

WCOZ

jumped to a 2.9 [share] right out of the box, and '

BCN

had a 1.9.”

“The purists among the radio elite in Boston were horrified,” Parenteau pointed out, “but the audience dug it.”

“[

WCOZ

] had a focus to their programming, and what had been an advantage at '

BCN

turned into a confusion,” David Bieber reasoned. “

WBCN

had a story to tell and their story got stolen; a

Reader's Digest

version of the station defeated them.”

“When '

COZ

happened, it was like a pail of cold water,” Tim Montgomery said. “I remember thinking at the time, âMan to man, we

are

a little indulgent.'”

“There was so much of that self-sanctioned, self-righteous thing in radio, and at '

BCN

, at the time,” added Parenteau. “For instance, if it was a windy day, each jock would come in with the same genius idea; you'd hear âWind' by Circus Maximus, âThe Wind Cries Mary' [from Hendrix], and âRide the Wind' by the Youngbloodsâforty-five minutes of fuckin' wind songs!”

Not only did Clark Smidt and his tighter playlist exploit the inconsistencies of a station where the individual radio shifts were self-governed, but also certain songs and genres either intentionally or inadvertently missed at

WBCN

became important building blocks of

WCOZ'S

programming. Ken Shelton stated, “'

BCN

played the Allman Brothers, but considered Skynyrd to be a cheesy bar-room rip-off. [But] people were calling '

COZ

: âPlay “Free Bird”! Play “Free Bird”!' '

BCN

stopped playing âStairway to Heaven.' They must have looked at the log and realized that they'd played it five thousand times; wasn't that enough? So, they started losing listeners to the âcommon man' radio station.” '

BCN'S

jocks reacted, feebly at first, not yet grasping the seriousness of the situation. “We just started making fun of them,” John Brodey remembered. “They were the fakes; we were the real deal.”

“They put on the cheesy announcers like Ken,” added Tim Montgomery. “Now, don't get me wrong, he's a fabulous guy and he [would have] a great career [later] at '

BCN

, but back then, my God, he sounded like . . . an announcer! He had a nice voice!” But, no matter how little regard the

WBCN

jocks had for their streamlined challenger, the disdain was not enough to prevent

WCOZ'S

steady rise.

Aside from the listener's acceptance,

WCOZ

also began to gain some measure of legitimacy within the music business as record labels recognized

the value of promoting their releases on “94 and a half.” As '

COZ'S

ratings swelled, a seesaw battle ensued, with each station racing to obtain exclusive association with the biggest talents of the day. Most often,

WBCN

could rely on the relationships it had fostered over the years with record promotion people and the bands themselves, many of whom had grown up with the station. However, that was not always the case, especially when

WCOZ

became more aggressive in pursuing its opportunities, as when Mark Parenteau pirated The Who right out from under

WBCN'S

nose. The original

FM

rocker had always enjoyed a tight relationship with the English band, dating back to even before Pete Townshend introduced

Tommy

on the air with J.J. Jackson in 1969, but that didn't stop Parenteau from recognizing an opportunity and then exploiting it to the max.

On 9 March 1976, The Who returned to play Boston Garden, and although scheduled to be on the air later that night, Parenteau still had time to see a good chunk of the band's performance before he'd have to leave. “While we were waiting for The Who to come on, all of a sudden there was this big commotion in the loge next to us; some trash was burning under the bleacher seats,” Parenteau remembered.

People started moving quickly, lots of screaming, “Get out of the way! Get out of the way!” This giant column of smoke rose up and hit the ceiling of the Boston Garden, then mushroomed out and settled back on the crowd. The fire alarms went on, all the emergency doors opened, and the Boston Fire Department came in with fire hoses to get this trash fire out. People were trying to find places to sit . . . in stairways, aisles; they moved people away from the fire, but they never closed the show down. Meanwhile during all this extra time, Keith Moon, the drummer of The Who, was doing what Keith Moon always didâgetting really fucked up backstage. I think on a good night, they had that all timed out so there wasn't this enormous break between bands, so he was just high enough to go on stage.