Radio Free Boston (17 page)

Authors: Carter Alan

Finally the lights came down and everybody went “

YEH

!” The fire's was put out, we weren't gonna die, and everything was great. The Who came on and started playing, but when they went into the second song, Keith was all over the place; he raised his arms, hit the drums, raised his arms . . . and fell backwards right off the drum [platform] and out of sight! So, off they went and the houselights came back on. Everybody was all tuned up on whatever drugs they were doing and [going] “uhhh . . . what?” There was still smoke in

the air, and it was cold because the doors were open; the fun had just been leached right out of it all. Then Daltrey came running [back] on and said, “It's a bummer; our drummer is ill! But, we're going to come back!” Everybody was booing, so we went backstage. I found Dick Williams and Jon Scott, the two heavies from

MCA

, the band's record label. They said, “Oh, Mark . . . terrible . . .”

“Listen, here's the hotline number; if you want, those guys can come over on the air and explain what just happened.” So I went back to the studio and told the whole story; the phones were buzzing with people being pissed off.

Parenteau was barely into his show when the hotline rang. “The security guard called and said, âThere's a Jon Scott down here with some other people and they want to see you.'” It was Roger Daltrey, who immediately wanted to go on the air. “He explained what had happened and said, âWe're going to come back,' and gave the date [1 April]. So, the next day it was in the newspaper; the article mentioned he had come by

WCOZ

. . . and '

BCN

had nothing to do with it. The ramifications were loud and long lasting. This was a major story, a major event at the Garden, a major band. That legitimized '

COZ

as being the right station at the right time, where the action was, and a nail in the coffin of '

BCN

âfor what they were doing at that time. Norm Winer [must have] gone out of his mind!”

David Bieber observed that it was a most difficult period for

WBCN

: “The station was searching for its own meaning and what it was all about; if 1976 was the real challenge and crossroads time, then '77 was the year of twisting in the wind and not knowing where to go.” Music was changing: from the radical underground rock of the late sixties and political Vietnam rants of the earlier seventies to a smoother, more mainstream, arena-rock style that sounded tailor-made for the streamlined

WCOZ

but was accepted with difficulty on the veteran station. Boston released its first album in September '76; Steve Miller's

Fly Like an Eagle

became one of the year's biggest hits; and

Frampton Comes Alive

spent ten weeks atop the

Billboard

chart. “A more uniform, bland tone pervaded the

FM

airwaves,” summed up Sidney Blumenthal in the

Real Paper

in 1978. “Rock became commercial culture.” David Bieber added, “You had some acts that were originally great

BCN

[artists] now crossing over significantly into Top 40. For example, the monstrosity that Elton John became: complete indulgence and decadence, costumes instead of content.”

The only member of the full-time staff who seemed to thrive during this time was Maxanne, whose original disposition toward rock and roll had pointed the

DJ

toward the future way back in 1970. Her passion had helped ignite Aerosmith's career, which by 1976 had resulted in two platinum albums, a handful of hit singles, and sold-out tours. A personal and professional interest in Wellesley singer and guitarist Billy Squier had helped his band Piper get a record deal with A & M, setting up his later, and significant, solo success in the eighties. Plus, as the

Boston Phoenix

reported in a retrospective article in June 1988, “Maxanne Sartori was an original champion of the Cars. Throughout '76 and '77 she played demo tapes of the band, providing it with a ready-made audience in a key college market when it signed with Elektra.” She told the

Boston Globe

in 1983, “I played the first Cars tapes so much that people at the station used to take the tapes out of the studio so I couldn't play them!”

“Maxanne was the only jock who was really rocking,” remembered “Big Mattress” writer Oedipus, who was similarly excited by what he called “the nascent rock and roll scene developing in the clubs.” Oedipus worked the morning show shift (paid by whatever records and tickets he could scrounge), headed home and slept all day, and then went out nightclubbing, returning to the station after last call. “I'd stay up and hang out with Eric Jackson or Jim Parry.” Not only did Oedipus get to know the overnight personalities at '

BCN

, but he was also there when the news department reported for duty in the early morning. “John Scagliotti knew that I got around town, so he said, âWhy don't you report on what's happening?' I was able to go to all the concerts, the cabaret shows and all kinds of cultural happenings.” Oedipus began taping one-minute reports that ran in the afternoon on Maxanne's show. “It got sponsored and I actually got paid. So, for my report, I made twelve dollars a week, and I sure needed it! On Fridays I'd get to '

BCN

and wait for Al Perry to sign the damn checks; that was my food.” Because of his associations with Maxanne and the news department, Oedipus was not left high and dry when his mentor Charles Laquidara left

WBCN

for the “Peruvian” mountains in 1976. “I said, âCharles, I should take over for you.' He looked at me and said, âOedipus, you'll never be hired at

WBCN

as a

DJ

!'”

With Al Perry, Norm Winer, and Laquidara gone, the rebuilding effort at

WBCN

began with the appointment of a new general manager, an experienced radio man named Klee Dobra, whom Mitch Hastings plucked from

KLIF

in Dallas. In late January 1977, the new boss brought in Bob Shannon, another outsider weaned on radio in Texas and Arizona, to assess the station and interview to be its next program director. Shannon camped out in a hotel room and tuned in the two radio opponents to see if he could determine why a young upstart was beating up Boston's legendary

FM

veteran. “What I discovered after listening for awhile was that '

COZ

was playing the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and Led Zeppelin [while] '

BCN

was playing Graham Parker and the Rumour. There was no question '

BCN

was too hip for the room.” Shannon went back to Dobra: “I said, âWith all due respect, three-quarters of the stuff I'm hearing on the radio station, I've never heard [in] my whole life. There's a lot of people that want to listen to this radio station: they tune in, [but] they hate what they get, so they tune out.'” After being hired, the new program director worked on a plan to rescue the station, concluding, “At the time everybody played exactly what they wanted, and as a result, when people were great, they were great. But when they were not in a good mood, it was awful. Plus, there was no consistency from shift to shift.”

Shannon had some record cases built and then called on the staff to recommend the best albums in each category of blues, jazz, folk, R & B, and rock music. He ended up with a core library of two thousand records, which became the bulk of the station's available on-air music. Then, only at certain times in each hour were the

DJS

given the freedom to access the additional, and gigantic, “outer” record collection. “The idea was to reduce the library to a workable number of tunes. In the beginning they hated it, but all of a sudden the station started sounding consistent.” Tommy Hadges, who had filled the morning gap following Charles Laquidara's departure, said, “We began to have an awareness and desire to look from show to show, to have some sort of flow so it didn't sound like six different radio stations.” But not everyone was amenable to the changes. The first to abandon ship was Andy Beaubien, who left his midday slot to pursue a career in artist management. Original '

BCN

jock Joe Rogers, who had been back at the station since 1972 operating under his new radio moniker of Mississippi Fats, also departed. “I was having more trouble with the changes than most people; I was having . . . less fun. I think ['

BCN

] was wonderful for a long time and I can see why it was necessary for it to change, and so it did. It isn't regrets; it was the sadness of watching . . . when all the jazz albums disappeared, all the blues albums, folk . . . . I felt, âI'm a dinosaur here.'”

Rogers signed off to pursue a dream he had fosteredâstarting his own restaurantâand Mississippi's Soup and Salad Sandwich Shop opened shortly after in Kenmore Square. Virtually an art gallery that served food, the establishment featured a wall décor of huge pea pods, images of mustard, and other edibles rendered in gigantic size by students at the Museum School. “It was a lot of fun,” the new restaurateur enthused. “We had real and imaginary sandwichesâpeanut butter to caviar. We charged people for peanut butter sandwiches according to their height: there was a pole by the cash register, and taller people would pay more. You could get a âGerald Ford' sandwich: cream of mushroom soup on white bread.” The pioneering disc jockey didn't forget his adventures at

WBCN

: “I had a sandwich named the âCharles Laquidara,' a custom prosciutto-based Panini with provolone and tomato. But prosciutto was so expensive that we would have had to lock it in the safe at night, so we compromised with Genoa salami.” He laughed, “We had a total of two customers who ever ordered the âGerald Ford'; but the âCharles Laquidara' ended up being much more popular than the president!”

WBCN

lost its most powerful and distinctive personality when Maxanne decided to toss in the towel, exiting after her final show on April Fool's Day 1977. “She was scared that I was going to change the radio station dramatically,” Bob Shannon concluded. But Maxanne also wanted to pursue a career in the record business, which made a lot of sense since she had always tuned in to new talent. Trading in her headphones, the jock picked up a job doing regional promotion for Island Records, later working in the national offices of Elektra-Asylum and eventually as an independent promoter. Replacing such a memorable talent was an important decision, and Shannon opted to move the infamous oddball Steve Segal (now referring to himself as Steven “Clean”), who had left '

BCN

for the West Coast and then returned, into the afternoon drive slot. “On the air he was either brilliant or awfulâno in between,” Shannon laughed. “One day he played a record by the Pousette-Dart Band and he came on the air and said, âThat reminds me of a game I used to play when I was a little kid, called “Pussydarts.” What you do is take darts, throw them at the cats and try to pin them down.' The animal-rights people went nuts. I mean, they were in the front lobby in thirty minutes!”

Shannon moved John Brodey into evenings and made him music director, and then planned to switch Tommy Hadges, who had inherited

the morning shift out of necessity, into the midday slot. But, finding the right talent for mornings was a daunting task. Shannon flashed on a

DJ

he never met but had heard regularly on a small Tucson radio station back in '72. “Matt Siegel did a night show there, and I used to sit in the bathtub, smoke a joint, and listen to him. I laughed a lot because he was so funny. So now, I started making calls . . . but I couldn't find him; nobody knew where he was. The only thing anybody knew was that he had done the voiceover on a regional Fleetwood Mac spot for Warner Brothers.” That actually was true: Matt Siegel had left Tucson and headed for

LA

, snagging a lucrative freelance job making commercials for record labels. When that opportunity eventually played out, he hit the streets looking for another job but couldn't find anything. With his money just about exhausted, Siegel phoned his best friend, who happened to live in Boston: “I said, âI have to come see you,' took my last $300, and got to my buddy's house in Brighton.”

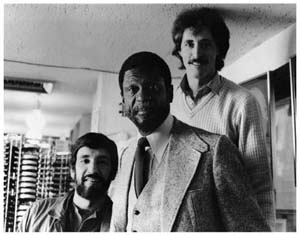

Charles Laquidara and Matt Siegel clowning around with Bill Russell. Who's taller? Photo by Eli Sherer.

Matt Siegel was now hanging out in the same city as Bob Shannon, but neither of them knew it. “There was this guy, Steven âClean,' who I met in

LA

, and he worked for

WBCN

,” Siegel continued. “I figured I'd call him

on a whim to see if there was something available because I was stone broke.” Siegel phoned, and then went to the station, but couldn't find the

DJ

. “I was just coming up zeros. So I said, âI'd like to talk to the program director.' I lied to them, saying, âIt's Matt Siegel from Warner Brothers in

LA

,' hoping the word wasn't out.” But, once his unexpected visitor's name was passed along, Bob Shannon sat there stunned; the coincidence too outrageous to be real. “I told the secretary, âAsk him if it's the Matt Siegel from

KWFM

in Tucson.' She came back and said, âYeah, that's who he is.' I couldn't believe it!”