Radio Free Boston (20 page)

Authors: Carter Alan

After his firing that Friday, David Bieber walked numbly to his office and then began to collect his things to remove from the station. “Charles had

already done his show and was out of the building, so I called him to tell him what was going on. His attitude was, âWe've got to mobilize; we've got to do something because they can't do this,' even though he wasn't one of the ones being terminated.” Bieber contacted the

Boston Globe

that afternoon, which ran a story the following morning, announcing that the entire

WBCN

staff, those fired as well as those who retained their jobs, would be holding an emergency meeting at 2:00 p.m. that day. A source, reported as “unidentified,” told the paper, “You'd better believe that a very wide range of possibilities, including a walkout, will be discussed.”

“I remember leaving that Friday and walking with Julie Natichioni from our sales department, talking and arguing about whether or not there'd be a vote for a strike,” Sue Sprecher recalled. “I can remember Julie saying, âCharles won't vote for a strike.' And I said, âOh yeah he will!'”

“I was influenced in a union household at a young age,” Mark Parenteau said. “When push came to shove, I could have kept my gig. But it was too horrible. They would have gotten away with it if Charles and I went back. I called my dad and he said, âStick with the union.'”

“Nixon had his Saturday Night Massacre and he lived to regret it, and you'll live to regret this too. You don't know this station and you don't know this town,” Danny Schechter hurled at Wiener as he was removed from the station premises (as reported by the

Real Paper

).

“We had been doing everything we could from the previous May or June until this February winter's day, with spit and glue and a little frosting in a can, to try and keep the station together, and they came in and just decimated it. [But] they had no idea what they were up against,” David Bieber related.

“They were misadvised,” concluded Oedipus, who was also a union shop steward. “They figured they'd fire half the staff and there'd be no power anymore. But they underestimated.”

On Saturday, someâlike Bieber, Schechter, or Laquidaraâmight have been fired up and ready for battle, but most of those terminated just appeared stunned, straggling into Tracy Roach's Back Bay apartment to discuss their future at

WBCN

, if any. Their rights under the union contract, even though not recognized by Hemisphere, were explained and discussed for hours. Wiener's hardline, confrontational, and nonnegotiating attitude seemed to indicate that the opportunity for compromise didn't exist, so the assembly eventually boiled down its options to a simple black or white

choice: give up or walk out. To Danny Schechter, the catalyst in bringing a labor organization into '

BCN

years earlier, it was absolutely clear what had to be done. But would other, less committed or nervous staffers agree? In the end, someone proposed a vote to strike, and the motion carried with only one dissenting opinion. The “News Dissector” was heartened: “People who were not really political got together and said, âWe have to fight this!'”

“It was an incredibly passionate time,” Sue Sprecher added about the final decision. “There was not a single doubt about what we had to do.”

After the vote, several in the group sat down to draft a public statement that everyone in the room could agree on. The work was finished by 5:30 p.m., and Laquidara called the radio station. The on-air jock, John Brodey, saw the hotline light flash and knew what was coming: “If the vote was for a strike, I'd get the call and be expected to walk out in solidarity.” He put Laquidara on the air, who began reading the statement: “

WBCN

employees, including all announcers and disc jockeys, news people, engineers, creative services, office people and sales staff, are on strike . . .” Moments later, he concluded with, “We call on all

WBCN

listeners, advertisers, and supporters to respond to our actions. We are taking these actions to save

WBCN

.”

“I told John,” Laquidara explained, “When you leave, just be sure everybody knows that the

real

WBCN

is walking out the door and that what people are going to hear after that is a bunch of pretenders.”

“I said, âOkay, I understand that,'” Brodey remembered. “Then I thought, âMan, this is really weird; I've got a song playing and I got to walk out.' But the company had the wagons in a circle; they had somebody out there waiting to jump in.”

As a managing employee of Hemisphere Broadcasting, the burden of responsibility now fell on Charlie Kendall. “The company guys came in and they said, âNo union!' I went, âThese guys are ingrained; you are not going to be able to break that union in this town.' They said, âYou just keep that station on the air!'” There was no option; if Kendall wanted to keep a job, he'd have to operate as an agent for the opposition.

“Charlie had to stay on because he was management, but he was totally supportive of the strikers,” Mark Parenteau said in sympathy.

“It really killed him when the strike happened,” added Jerry Goodwin. “All of a sudden we couldn't talk to him anymore. I didn't envy his position.” Putting in some calls, Kendall located a few

DJS

who, as he put it, “were, basically, starving.” The program director explained to them that they

would be vilified during the strike and, if the union won, then they would most likely never work in Boston radio again. Nevertheless, a few who were willing to cross the inevitable picket lines stepped forward.

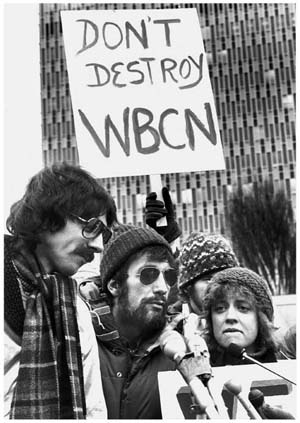

On strike!

WBCN'S

Mark Parenteau, Charles Laquidara, and Sue Sprecher meet the press at the picket line in front of the Pru. Photo copyright by Stu Rosner with courtesy from the

Boston Phoenix

.

Kendall himself kept the station on the air after Brodey's walkout, playing song after song until six, and then, according to the

Boston Phoenix

, “aired a taped Queen concert, followed by a taped Blondie concert (an affair at the Paradise hosted, ironically, by Oedipus), followed by a taped Steve Miller concert. It wasn't until after midnight that the actual live voices of strikebreaking announcers began to come over the airwaves.”

“There was no automation, so it had to be live jocks,” Kendall mentioned. “I remember one guy came down to the station who had one arm!” Nevertheless, the applicant demonstrated that he could cue up a record and perform the other required tasks to run a radio show, so Kendall impressed him into his ragtag group of replacements. Michael Wiener arranged for a few pros to jet in from his other properties in San Jose and Jacksonville, and soon the alien voices had taken over the high ground. That they were thrown off somewhat by the sudden reassignment could be heard from time to time: Alan MacRobert in the

Real Paper

reported that one of the announcers forgot where he was and identified the station as “

WBCN

, Chicago.”

While Michael Wiener sat in the nearly empty

WBCN

office with a skeleton crew of Kendall, Tim Montgomery, the chief engineer, a worker in the accounting department, and the motley assortment of replacement

DJS

, the striking staffers got right down to business, organizing themselves with the help of Phil Mamber from the

UE

. A list of demands was drafted, including recognition of the union and reinstatement of all fired employees, and then presented to Hemisphere's president. Wiener summarily rejected its arguments, telling the

Boston Globe

, “The union was recognized by the previous owner, but that contract is non-assignable.” Matt Siegel acknowledged this in a prepared statement, saying that the

FCC

informed their union that the new company “need not accept a contract negotiated by the old

WBCN

, but it must recognize the United Electrical Workers, the union that has been certified by the federal government as our legal representative. This, the new management has refused to do. Rather than sit down with us to resolve our differences, they choose to misrepresent our cause and malign our union.”

By Monday, 19 February, at 9:00 a.m., the entire group of striking employees,

with a cloud of supporting station volunteers and concerned listeners, had thrown up a picket line in front of the Prudential Tower and then held a press conference to announce the strike in greater detail. The following morning, both of the city's premier dailies, the

Boston Globe

and the

Boston Herald American

, featured articles about the action, including nearly identical photographs showing the circle of picketers braving the February chill, with producer Marc Gordon in the foreground holding aloft a sign that read, “Don't Destroy

WBCN

.” Both of Boston's foremost weeklies, the

Real Paper

and the

Boston Phoenix

would soon chime in with their own in-depth articles, thus beginning a nonstop rush of media attention, including scrutiny from national stalwarts the

New York Times

and

Rolling Stone

magazine. “There was such participation by both local and national media,” David Bieber recalled. “People like Jeff McLaughlin of the

Globe

covered it almost on a daily basis, which was unprecedented.”

While Phil Mamber and the

UE

filed an unfair labor practices suit against Hemisphere with the National Labor Relations Board, the rank and file of Local 262 strategized. Danny Schechter realized that it was a long shot, but in this situation, their union actually had a chance to win. Gathered under one collective bargaining agreement, the

WBCN

staff, with all its departments, displayed a unique strength that made victory possible. Schechter explained, “It's completely unusual in broadcasting because of the craft union structure, [for instance,] the engineers in one union and the announcers in another. There's never really the unity [needed] to beat the company; they could play different people off one another.” With everyone gathered together in the

UE

, the

WBCN

strike committee began to set up responsibilities based on its many members' unique abilities. Jerry Goodwin recalled with a laugh, “I was on the âknee-busters' committee. Our job was to go to the Sheraton next door to '

BCN

, where all [the replacement

DJS

] were staying, and wait for them to come out of their door and suggest that they just get in their car and hit the road, as simple as that. We threatened to ruin their car . . . but never did. We didn't have to; they were outta there!”

“It was called the âDirty Works' committee,” Oedipus clarified. “We would call those guys up on the hotline all the time, harass them, and a lot of them walked.” The punk jock also performed another, more surreptitious and clandestine job as an actual

WBCN

secret agent. “I would meet with Charlie Kendall to find out what was going on over on the other side. We would meet downtown in a movie theater and sit next to each other. It

really was like âDeep Throat [from the Watergate scandal].' I saw one of my favorite films,

The Warriors

, three times with Kendall.”

Oedipus lists the strikers' demands while a concrete overhang protects the crowd from a cold February rain. Photo by Sam Kopper.

The other committees were more high profile and, somewhat, less scandalous. David Bieber fed the media a steady diet of information from the strikers and organized support from his contacts, while Tony Berardini, as music director, worked through his Rolodex. “It was my responsibility to talk to the guys from the record labels and see if they would support the strike, and they all did!” Berardini became the station's mouthpiece to all the national music trade magazines, including

Radio and Records

,

Album Network

, the

Gavin Report

, and

Record World

. He also left Boston midstrike and traveled with Kenny Greenblatt to the

Radio and Records

convention in Los Angeles, where he was given generous podium time “in a room with seven hundred people” from the music industry to explain and urge support for his union's actions.