Radio Free Boston (21 page)

Authors: Carter Alan

The striking sales representatives received the task of cutting off the flow of money to the station. Sue Sprecher explained, “I think they were the ones put in the toughest spot of all. They had to call up their clients and ask them

not

to advertise on

WBCN

, after years of working on those [relationships].”

“One of the key factors was that we reached out to the advertisers and told them that this was not the real '

BCN

,” David Bieber pointed out. “If they were spending their money, they weren't getting their money's worth.” In mere days, the sales staff achieved remarkable results; by Wednesday the 21st, Boston University's

Daily Free Press

reported that most of the advertisers on

WBCN

had thrown in their support for the strikers and withdrawn their commercials. Jim Parry told the student newspaper, “Most advertisers withdrew their spots because the station they bought isn't what they're getting.” By the end of the strike's second week, the only major advertiser yet to pull commercials off the air was Don Law. Since Charles Laquidara had known the concert promoter for many years, his assignment was to convince the impresario to follow suit. “That was a big deal,” Steve Strick said. “Charles really worked on Don.” To be fair, the

Real Paper

revealed that Law provided the Orpheum Theater at cost for a strike benefit concert on 4 March [and another a week later] and then reported, “But he has yet to match the extraordinary steps taken last week by other local corporations such as Brands Mart, Rich's Car Tunes, Tweeter Etc., and Strawberries. In addition to removing all advertising from the struck station, these companies have also donated

paid commercial time

on other radio stations to advertise the striker's benefit.” As published criticism began to mount, Law fell in line after realizing how important his company's action would be to the strikers' efforts: “I spent a lot of time with Charles and I was responsive to what he said. We followed his lead and pulled our commercials.”

“It was one thing for the newspapers to give [the strike] coverage, which they did, but they [also] ran ads in our support at no charge,” David Bieber marveled. “I was connecting with people like Peter Wolf and the J. Geils Band to run ads in support of the strikers and the listeners who marched in the picket lines, and to do concert benefits for the people who were out of work. Don't forget, this was February 1979, dead of winter, freezing cold.” Within days of the walkout, the J. Geils Band had published “An Open Letter” to Michael Wiener regarding “The Strike to Save

WBCN-FM

,” insisting “that any station endorsements made by members of our band be immediately removed from the airwaves until negotiations are completed.” Peter Wolf concluded the letter by writing, “Personally, as a former

WBCN

disc jockey, and now as a listener, it saddens me that such estrangement between management and staff has occurred at a time when I feel the station was sounding better than ever.” Then there was the very quotable

closer: “P.S. The only scabs I dig are the ones on my elbow.” In short order, all of Boston's biggest bands had published their own manifestos of support, including Aerosmith: “These people need us and we need them”; the Cars: “We will never forget

WBCN'S

contribution to us. Let the Good Times Roll . . . Again”; and Boston: “There's no place like home and

WBCN

is a part of our home. Let's keep it that way.” A consortium of local band managers, club owners, and musicians joined forces to declare their support in the press, and then backed up that statement by offering their talents and services to the strike committee.

Those offers were swiftly organized since there was an immediate need for funds to buy groceries for striking employees, pay their bills, and avert the pressure of being forced to consider work elsewhere. The most visible benefit concert was the Orpheum Theater show on 4 March, featuring James Montgomery, the Fools, the Stompers, and Sass. All the bands worked for free, and even the lighting and sound technicians, with all their equipment, refused a paycheck. Members of the striking '

BCN

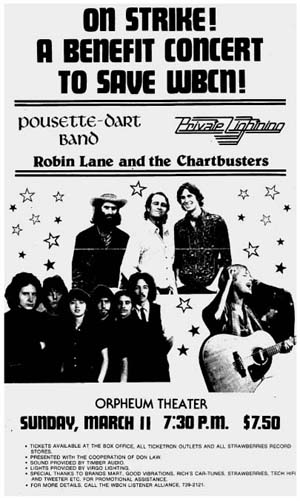

staff took the stage between acts to plead their case and thank the listeners who had stampeded down to Tremont Street to sell out the old theater. Then the J. Geils Band capped the evening with a high-octane surprise performance. This Sunday-night show was so successful that the strikers planned a second event for 11 March, featuring other A-level Boston bands: Robin Lane and the Chartbusters, Private Lightning, and Pousette-Dart Band. Using his relationship with the Rat in Kenmore Square and contacts among the Boston punk community, Oedipus spearheaded a weeklong series of nightly benefits featuring the cream of the new “underground” scene, while a major North Shore fundraiser at the Main Act in Lynn featured the Neighborhoods, Human Sexual Response, and more.

FM

, the movie depicting a fictional radio station's labor struggle, was given special benefit showings at the Orson Welles Cinema in Cambridge. “The movie depicted a strike at a radio station purported to have the same kind of spirit

WBCN

had,” David Bieber observed. “But, in ninety-minutes, how do you tell a tale comparable to what we went through . . . a real, ferocious, on the street battle. No way

FM

could do justice to what we endured in the end.” But how appropriate it was that a Hollywood yarn about a West Coast radio strike would help to fund a similar, but very real, drama unfolding in Boston.

With the staff locked out, and throwing up daily picket lines in the broad plaza in front of the Prudential Tower, the nerve center of the newly formed

WBCN

Listener Alliance was established in a home with donated space on Braemore Road in Brookline. Clint Gilbert, a part-time manager of the expatriated Listener Line, designated a recent recruit named Paul Sferruzza (later known to '

BCN

listeners as “Tank”), as the person on location who was in charge of the volunteers. “Darrell Martinie's agent was the guy that came up with that venue,” Tank recalled. “We had our little work area, a bathroom, two bedrooms, and a kitchen space. People who had worked the Listener Line [in the Prudential] came in and worked their shift in Brookline.” Gilbert mentioned, “We got three or four phone lines in, and once we were able to get the new phone number out, 617-

SEX

-2121, they were ringing!” David Bieber, working with his sympathizers in the print media, managed to obtain nearly daily ads in the papers listing the

WBCN

strike events and the new phone number to replace the so-familiar 617-536-8000, although the more discrete numeric

ID

, 617-739-2121 (without the

SEX

part), was the one that made it to print. Tank pointed out, “The whole focus in Brookline was on the strike and raising money so that guys like Matthew Wong, who was a veteran sales person, could pay his bills.” Clint Gilbert shook his head at the memory: “The listeners were so willing to help; the caliber of what people were offering was nothing like I've ever experienced. âJust tell me, what do you guys need?'”

The second benefit concert at the Orpheum Theater. Boston's bands help keep the striking employees afloat and the fight alive. Courtesy of Clint Gilbert.

As donations poured into Brookline, and some listeners just pressed cash into the hands of picketing volunteers at the Pru, another drive was on to demonstrate to the new owners just how much the community supported '

BCN

. Listeners were urged to send Michael Wiener and Hemisphere Broadcasting letters of protest, or flood its Prudential Tower office with calls. Dozens and dozens of station fans converged on Boylston Street daily to augment the circle of striking protesters and march in solidarity. A “Duane Glasscock Victory Motorcade to Save

WBCN

” was organized for Saturday, 24 February: “A magical mystery tour of Boston,” according to the leaflets placarded all over the city by droves of volunteers. The

Boston Sunday Globe

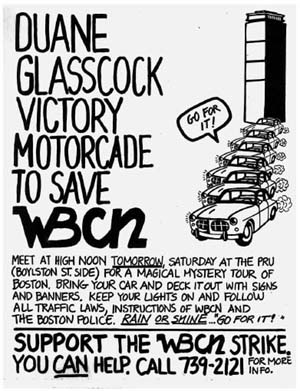

reported the next day that eighty cars, “many festooned with posters, balloons and banners,” accompanied by a police escort, staged a peaceful, promotional drive through the city during a hard rainstorm. “My car was âThe Big Mattress' car,” Tom Couch recalled with a laugh. “I had a Honda Accord, and we tied a big, old mattress on top of it.”

Halfway into the second week of the

WBCN

strike, Mitch Hastings stepped off a plane at Logan Airport, after having vacationed in Bermuda

following the station's sale. The

Boston Phoenix

caught up with the former owner and asked him what he thought of the furor that had erupted in his absence. Hastings, who appeared fully aware of the strike, was nevertheless shocked at what had transpired. “It's nothing like what we expected. We thought we were selling the station to a company that would carry on our programming and staff with a minimum of changes. I talked to him [Wiener] today and I get the impression that he still wants to carry on

WBCN'S

image, and standing, but he doesn't quite know how to do it.” A softening attitude from the top of the Pru? It certainly seemed so. The article revealed, “Faced with the continuing loss of '

BCN

advertisers and

complaints from long-time listeners about the absence from the airwaves of their favorite personalities, Wiener did agree to a sit-down session with representatives of Local 262 of the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America.” Jeff McLaughlin at the

Globe

wrote, “The union, led by field organizer Phil Mamber, refused to back down from any of its demands: Reinstatement of every staff member, recognition of the union for collective bargaining and negotiation with the union over any layoffs.” Wiener, in the article, admitted that the loss of advertising revenue was “beginning to really hurt.”

Motorcade promotional flyer. Go for it! Courtesy of Tony Berardini.

Then, in a moment of perfect timing, as round-the-clock bargaining sessions stretched on for a week, Arbitron published its radio rankings for January 1979. The figures showed that immediately prior to the strike,

WBCN'S

popularity with all Boston-area listeners older than age 12 had rebounded into the number 6 position in Boston with a 4.7 share. At the same time,

WCOZ'S

ratings had softened to a 4.3, earning that station the number 7 slot. This news prompted Wiener to redouble his efforts to settle affairs at the negotiating table and move on. In swift order, the two sides finally hammered out an agreement, and the union dropped its suit in response. When the sudden announcement emerged that workers would be expected to report back to work on Monday, 12 March, everyone suddenly realized, with a start, that the

WBCN

strike was actually over.

Jubilation exploded as the amazing news spread. “I never expected to win,” Steve Strick admitted. “I totally expected that all that protesting was just for show, and that at the end of the day we'd basically be looking for jobs. The fact that they hired us back was huge . . . history making!”

“It was truly one of the highs of my life, the night after we won the strike,” Sue Sprecher said. “I remember being at Mark Parenteau's place and we were all singing âWe Are the Champions!'”

Danny Schechter, channeling some (very appropriate) hippie idealism that harkened all the way back to the scribing of America's founding fathers, wrote in the strike victory press release, “We hope that our efforts can be an example to others in the Communications Industryâto show everyone that unity is strength; that colleagues should care about each other and support each other; that principles are worth defending; and that working people do have rights which are worth struggling to secure.” The already-scheduled 11 March solidarity concert at the Orpheum Theater was hastily, and happily, relabeled a “Victory Benefit” as a humbled, and

candid, Michael Wiener told the

Boston Globe

, “I'm thrilled the strike is over. I've never seen anything like it. Clearly, I miscalculatedâto mount an effort like they did is just extraordinary. What can I say? I'm happy as hell we're all on the same side now.”