Rampage (16 page)

Authors: Lee Mellor

Staatsarchiv Bremen

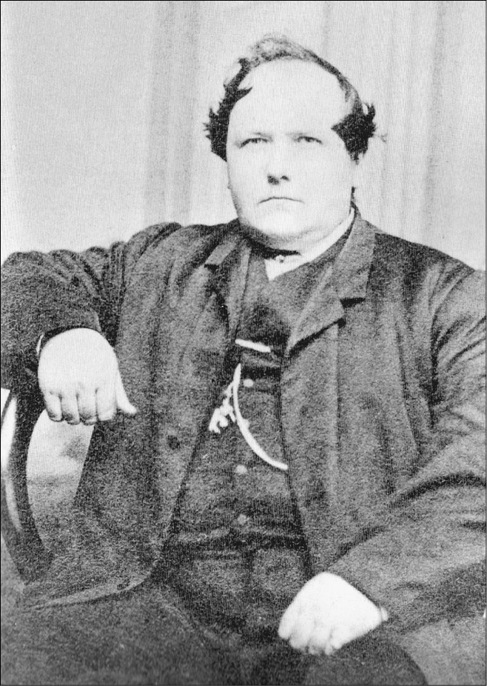

Alexander Keith Jr.

The Dynamite Fiend

“What I have seen today, I cannot stand.”

Victims:

81 killed/50 wounded/committed suicide

Duration of rampage:

December 11, 1875 (serial mass murderer?)

Location:

Bremerhaven, Germany

Weapon:

Time bomb

Whoops

In December 1875, the fledgling German nation was truly coming into its own. Prussia’s crushing victory over France in 1870/71 had laid a strong foundation upon which to unite the German principalities into a formidable European power. Under the guidance of that genius of

realpolitik

Otto von Bismarck, Germany had prospered, industrializing and forging an empire that would ultimately challenge Britain for supremacy in the First World War.

Docked in the port of Bremerhaven, the transatlantic steamship

Mosel

represented the height of Germany’s engineering brilliance and affluence. On December 11, 1875, a crowd of passengers huddled on the dock waiting to board, their breath like smoke on the frosty sea air. Using a winch, a group of stevedores was hoisting a large wooden barrel onto the ship, when suddenly the keg slipped and plummeted, landing on the dock. A fiery blast tore through the ropes and metal, evaporating the snow and blowing charred bodies in all directions. Twisted iron shrapnel and shards of glass flew like stray bullets, shredding flesh and ripping clothing from the dead and maimed. The

Mosel

’s bow caved as smoke billowed from a hole blown in the vessel.

In his cabin below the deck, a portly bearded man calling himself W.K. Thomas sat down at his desk. The smell of schnapps hung heavy on his breath, the numbing elixir doing little to steel him against the images of screaming amputees and blackened corpses — a grotesque scene he had never intended to witness. Pressing the tip of his pencil against the paper, he jotted out a terse farewell to his wife: “God bless you and my darling children, you will never see my [

sic

] to speak to again. William.” His second letter, to the ship’s captain, was much longer:

To the captain of the Steamer Mosel Please Send money you will find in my pocket — 20 pounds sterling 80 marks German money My wife resides at 14 Residenze Strasse Strehlen by Dresden What I have seen today I cannot stand W K Thomas

[34]

Then, after removing his jacket, he planted his sizable girth on the divan and drew a revolver. Two pathetic gunshots rang out, mere pin drops in comparison to the thunderous boom that had shaken the harbour minutes earlier. Nobody noticed. Only later, when a rescue crew boarded the

Mosel

, was an anguished moaning heard emanating from the cabin. Breaking down the locked door, the rescuers found the balding and bloodied Thomas unconscious on the floor, presumably injured in the explosion. Yet his cabin had been locked from the inside. An inspection of the room revealed a revolver with four bullets in its chamber lodged under the couch. The strange passenger had fired twice into his head, one shot tearing through his cheek and embedding itself in his right cortex. Paralyzed on his left side, he was like a beached whale helplessly awaiting death. The medics rolled him onto a stretcher and struggled to carry him to the harbour barrack. There they laid him alongside the scores of debilitated and dying passengers.

Suicide note penned by Alexander Keith Jr., under the alias of W.K. Thomas.

Suicide note penned by Alexander Keith Jr., under the alias of W.K. Thomas.

Staatsarchiv Bremen

Little did they know that the man they had strained their backs to save was the cause of all this anguish. Thomas’s botched suicide was merely an echo of his greater foible: an elaborate time bomb, inadvertently triggered too soon. He had concealed the device in a wooden barrel, much the same way he masked his true identity. In time, the corpulent package that was W.K. Thomas would also be destroyed, and the villainous Alexander Keith Jr. would return to the public conscience, not just as a Confederate spy and con man, but as the worst mass murderer of the nineteenth century.

The Nefarious Nephew

Since the opening of his Nova Scotia brewery in 1820, Canadians have associated the name Alexander Keith with the comforting flavour of hops and malt — widely regarded as a top-shelf India Pale Ale by laymen, and a poor imitation by connoisseurs. In 1817, twenty-two-year-old Alexander Keith Sr. immigrated to Halifax from Scotland. Within two decades, he had established himself as the most powerful and industrious man in the city. Apart from owning what would become one of North America’s oldest breweries, Keith was also elected mayor on three occasions, served for thirty years as a member of the legislative council, and acted as Provincial Grand Master of the Maritimes for the Freemasons. Unfortunately, his nephew and namesake, Alexander “Sandy” Keith Jr., shared his uncle’s ambition but lacked his work ethic and delight in public service. Sandy, thus called for his red-tinged hair, was born in Halkirk, Scotland, on November 13, 1827. With the economic downturn of the early 1830s, his father, John Keith, took his wife and three children on a gruelling six-week ship voyage to join John’s wealthy brother Alexander in Halifax. Sandy first set foot on Canadian soil at the age of nine. In 1838, John Keith decided to place himself in direct competition with his older brother, opening the Caledonia Brewery, an unimpressive wooden building on Lower Water Street. John’s aspirations were bold, but in reality, he stood little chance against Alexander’s clout. Perhaps the first indication of young Sandy’s Machiavellian leanings was his decision to forsake his struggling father and work in a clerical position for his successful uncle. To add further insult, Sandy added “the Younger” to his name, in an effort to pass himself off as his uncle’s son. Later, as he grew older and more rotund, he would actually assume “the Elder’s” identity when it suited him.

A young Alexander Keith Jr. posing, circa 1865.

A young Alexander Keith Jr. posing, circa 1865.

Staatsarchiv Bremen

Knowing that his cousin Donald was heir to the Keith dynasty, the avaricious Sandy sought to gain his fortune any way he could. Initially he tried his hand at forgery, but by the age of twenty-nine he had switched to what would become his standard modus operandi: money scams involving fire. In 1834, Sandy was suspected of throwing a muslin bag drenched in turpentine and stuffed with wood shavings, charcoal, cotton, and wadding through the window of a warehouse he had insured. Though the crude contraption did little more than scorch the floor, had it ignited, the residents of the boarding house upstairs would have been roasted alive.

Sandy’s first foray into bombing on August 14, 1857, was marked by a meteor shower — a grim omen of the fires to come. Shortly after midnight, the merchants’ powder magazine, containing the whole stock of gunpowder in Halifax, exploded, destroying five houses in the city’s poverty-stricken north suburb. The government magazine and barracks were similarly devastated, along with several houses, causing an estimated $100,000 in damages. One man was killed in the blast and fifteen others wounded. The town’s alderman concluded that a stray meteor must have struck the building, but his theory was soon disproved when a farmer in a nearby field happened upon a stone from the barracks embedded ten inches into the dirt. The projectile was caked in gunpowder and wax with a three-inch wick protruding from it. Investigators concluded that an unknown rogue had carefully crept into the magazine and placed a candle with a lengthy wick inside. After igniting it, the intruder would have had sufficient time to flee before the explosion tore the neighbourhood to shreds.

If not for his social connections, Sandy Keith would likely have been charged with the crime. At the time, he was working as a civil engineering agent, and frequently visited the magazine. Coincidentally, the magazine keeper, Samuel Marshall, had been bedridden with illness for six weeks leading up to the explosion and had entrusted the only key to him. Sandy also had a motive. His uncle, Alexander Keith, had poorly organized and invested in the construction of a railroad running west from Halifax to Windsor, Ontario. Foolishly, he had employed Sandy to manage his contractors, all of whom needed access to gunpowder. His nefarious nephew was charged with transporting it by wagon from the magazine to the railroad lines, where he would supposedly sell it at twenty-five cents a pound. However, railway investors suspected Sandy was purchasing the powder at half price from other contractors so that he could retail it at the regular price and pocket twelve and a half cents from every sale. The destruction of the Halifax merchants’ powder magazine had conveniently obliterated all evidence of the surplus gunpowder that Sandy claimed to have sold. The few merchants who dared insinuate that Sandy was responsible for the explosion and demanded financial compensation for their losses were quietly paid off by the Keith family. In Alexander Keith’s Halifax, saving face was more important than seeking justice for the man his nephew had murdered and the scores of working-class Haligonians he had left crippled and destitute. Sandy seems to have taken the lesson to heart: little people — the poor, the enslaved, even the bourgeoisie — were disposable. Life was war, and only the ruthless became rich and powerful.

An Evil Existence

Leading up to the explosion of the

Mosel

, Alexander Keith Jr.’s legacy of crimes and inhumane acts is enough to fill an encyclopedia. Halifax had long prospered as a midway point between southern cotton plantations and British textile mills, so when the American Civil War broke out in 1861, it was in the interest of most Haligonians to support the Confederacy. Sandy Keith, a notorious racist and opportunist, went a step further, aiding and abetting blockade runners and pirates. He opened the Halifax Hotel to house them while they were in port, and spent many an evening puffing cigars and clinking champagne glasses with fine southern gentlemen, whose style and attitudes he learned to emulate perfectly. Sandy also collaborated with Confederate agents on (usually botched) terrorist attacks launched from Canada, including one particularly vile plan to send clothing infected with yellow fever to Yankee cities. Considering that the disease was spread by mosquitos, the operation was doomed to failure. If we are to measure a man by his intent rather than his success, it is clear that Alexander Keith Jr. had no compunction about using biological warfare on civilian populations.

When his father died in July 1863, Sandy left his uncle’s employment. A variety of reasons for his departure have been given: Alexander Keith Sr. pressuring him to marry his spinster cousin; Keith Sr.’s support for the American federal army; disagreements with his uncle’s business manager; and most likely, his constant shaming of the Keith family name with his sordid reputation. Ideology and loyalty always came second to profit on Sandy’s list of priorities, and it wasn’t uncommon for him to charge his Confederate allies top dollar for goods only to fill ships bound for Dixie with spoiled food stuffs. In fact, such was his selfish duplicity that he took to sleeping with a revolver under his pillow, lest one of the countless men he had swindled come seeking revenge.

One of Keith’s favourite cons became insuring goods to be transported by vehicle, then manipulating events so that they would be lost or destroyed, and making a fortune in compensation. Confederate blockade-runner John Smoot groomed Keith for a smuggling operation in which Keith would purchase two train engines in Philadelphia for $85,000, then sneak them past Yankee customs officials into Dixie, where Smoot could use them to transport cotton from Virginia to the ocean. It would have been a lucrative enterprise for Smoot, but Keith twisted the southerner’s trust to his own advantage. Under the identity of A.K. Thompson, he travelled to Philly, and on July 7, 1864, ordered the engines from the Norris Works company for $25,000. However, he had convinced the Petersburg Steamship Company and George Lang’s quarrying business to also invest $20,000 and $40,000 respectively in the same engines. By mid-August they were ready, and, under the surveillance of customs agents, placed on a ship bound for Halifax. But instead of honouring his word, Keith informed the War Department that the engines were actually heading south, and they were seized. Keith returned to his investors with a sob story about how the authorities in Philadelphia had learned he was an infamous Confederate agent and taken the contraband. Having no idea that three separate entities had entrusted him with money to purchase them, the individual investors reluctantly shrugged off their financial loss as a casualty of war, and Sandy Keith came out of the situation with a $60,000 profit. Eventually, all three investors would learn they had been duped, but only Luther Smoot swore vengeance and meant it.