Rampage (18 page)

Authors: Lee Mellor

After the

Mosel

Alexander “Sandy” Keith Jr. made two catastrophic mistakes on December 11, 1875: prematurely blowing up the

Mosel

, and failing to competently blow off his own head with a pistol. For rather than escaping into the unknowing bliss of death, he awoke to find himself in a makeshift hospital, surrounded by the agonized moans of his victims. Having suffered neurological damage, he had lost all feeling on the left side of his body, and his faulty eyes now saw the world in a permanent blur. Suspicious, the doctors began questioning him about the reasons for his attempted suicide. Yet the bullet had not eliminated his tremendous capacity to deceive, for that lay at the very foundation of the man’s character. Therefore Sandy competently maintained the guise of W.K. Thomas, lying that he had shot himself because he could not bear to be bankrupt. In a vain attempt to appeal to his conscience, the incredulous doctors notified him that he was dying and had only limited time to confess. When that didn’t work, police interrogators soon arrived, and used wine to loosen his tongue. They brought along two ace cards: the insurance broker, and one of the clockmakers, a man called Bruns. Nevertheless, Sandy’s poker face never faltered. Chief Inspector P.J. Schnepel then reminded Keith about the precarious future of his children, and something inside his cold heart stirred. He began a confession of sorts, laden with lies and half-truths. He told them that he was really a German-born blockade runner raised in Virginia, and went by the name of William King Thomson. To escape his sordid past, he had adopted W.K. Thomas as a pseudonym. He blamed the explosion on a broker named Skidmore — a man who had shipped the barrel containing the time bomb to him along the Rhine. Though that was indeed true, Sandy attempted to paint himself as Skidmore’s unknowing accomplice. He added that he felt no remorse and wasn’t a bad man, which, given his bogus story and suicide note, is difficult to understand.

Four days after his botched suicide, Sandy was caught trying to peel away his bandages in the hope of bleeding out, rather than admitting the truth. That it was he whose power over life and death now rested firmly in the hands of others is poetic justice. The doctors had no intention of letting him croak before he fessed up. Increasingly, journalists and rubberneckers gathered around the dying man to hear his incoherent and incongruent accounts of the bombing. Given the testimonies of the insurance broker and three clockmakers, the only person Sandy Keith was fooling was himself. The media had already deemed him guilty, labelling him the Dynamite Fiend, as many attributed his crimes to demonic possession. Newspapers across Europe and North America ran article after article, expounding theories of his criminality, analyzing the mechanical efficiency of his time bomb, and decrying the immorality of this new scientific age that would surely bring the world to ruin.

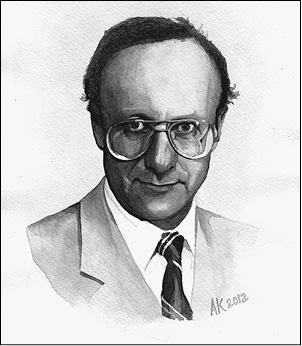

Alexander Keith Jr. after death.

Alexander Keith Jr. after death.

Staatsarchiv Bremen

Eventually, investigators at Bremerhaven learned the identity and whereabouts of Sandy’s wife. As Cecelia languished in Villa Thomas, distressed over Sandy’s disappearance, she received a visit from a detective who informed her that her husband had attempted to take his own life. He escorted Cecelia to Bremen by train. Upon arriving, she was told of Sandy’s involvement in the explosion. As she struggled to digest this information, local investigators launched into a full-scale interrogation. At some point during the questioning, Cecelia stumbled and referred to her husband as Alexander. Realizing her slip, she demanded to speak with John Steuart, the American consul in Leipzig and a close personal friend. Sensing a change in the tide, the investigators switched tactics, offering to take Cecelia to Bremerhaven to see her dying husband. There were two stipulations: police officers were required to be present, and any conversation between the couple had to be in German. By the time they permitted Cecelia to visit her husband, Sandy was lingering at death’s door. Observing his wretched state, Cecelia begged the doctor to kill him. She pleaded with her husband to repent so that one day they would be reunited in heaven, but Sandy remained defiant. When she left him, he was barely alive. It is fitting that, having lived his whole life in deceit, the last words to escape his lips were lies: “I have been a thick-head. The fellows in New York are guilty.”

Despite his efforts to maintain the facade of W.K. Thomson until his dying breath, Sandy’s elaborate deception inevitably came unravelled when world-renowned detective Allan Pinkerton was hired onto the case. In early 1876, he sent a report to Detective Schnepel containing a wealth of evidence indicating that the mysterious W.K. Thomas was in fact Alexander Keith Jr., the nephew of a famous Canadian brewer. Satisfied, Schnepel gladly paid Pinkerton’s fee of $642.42, and at long last revealed the identity of the Dynamite Fiend to excited newspapermen across the globe. With his body buried in a pauper’s grave and his name quickly fading from the headlines, all that remained of Alexander Keith Jr. was his head — severed from his body post-mortem. From the breweries of Halifax to preservation in a large bottle of alcohol, Sandy had come full circle. In a final ironic twist, his head was obliterated during an Allied bombing of Bremen in the Second World War. The distant, mechanized methods of destruction Sandy had ushered in to make him a “somebody” were the same weapons that erased all trace of his corpse. Among numerous other crimes, he is also suspected of sabotaging Patrick Martin’s ships bound from Montreal, as well as the lost

City of Boston

in 1870. Though never convicted of homicide, in all likelihood Alexander Keith Jr. was the worst permutation of predator: a serial mass murderer.

Part B

Personality Disorders

Following an incidence of multiple murder, the general public invariably asks, “Why?” How could somebody ruin the lives of so many innocent people with such callous disregard? Our political leaders throw up their hands in apparent frustration, labelling the murders “senseless” and beyond our collective understanding. Whether their words are sincere or a dubious attempt to feign identification with the average Joe, the fact is that over the past two hundred years, criminologists and mental health experts have uncovered a plurality of explanations for these heinous acts. The stories contained here will examine just some of the mental disorders found among criminals who have been convicted of multiple murders. Among them are narcissistic and anti-social personality disorders as well as psychopathy.

The fallout from the December 14, 2012 massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School necessitates a clarification before we dive in. Compounding this recent tragedy, the American news media placed undue emphasis on the fact that gunman Adam Lanza suffered from Asperger’s Syndrome. The resulting stigmatization of this condition prompted the Autistic Self Advocacy Network to issue a statement clarifying that the mentally disabled were “no more likely to commit violent crime than non-disabled people.” For the most part, this is true; in fact they are statistically more likely to become victims. Unfortunately, we cannot say the same about narcissists, antisocial personalities, and psychopaths. To quote the forensic psychiatrist Dr. Michael Stone:

Certain personality disorders are distinctly over-represented in the annals of violent crime. Besides narcissistic personality or traits thereof — which underlie almost all types of violent crime, antisocial, psychopathic, sadistic, paranoid and explosive-irritable types are particularly common in this realm.

*

Nevertheless, it is crucial to understand that the majority of people diagnosed with these conditions

do not go on to kill

. The presence of one of these personality disorders simply elevates the likelihood that violence will occur. Human beings are too complex for there to be a single explanation for our behaviour. This does not mean that rampage slayings are incomprehensible, merely complicated. By learning the basics of the three personality disorders commonly found in multiple murderers, we begin to take small steps toward a greater understanding. For an example of a Canadian mass murderer suffering from paranoid personality disorder, please consult the case of

Pierre Lebrun

(Chapter 10).

Caution: Though well-versed in the subject matter, the author is not a trained mental-health professional, and is theoretically unqualified to make a formal diagnosis. Please keep this in mind when reading the following assessments.

*

Michael H. Stone, “Violent Crimes and Their Relationships to Personality Disorders” in Personality and Mental Health 2 (2007), 150.

Chapter 4

Narcissists, Anti-Social Personalities, and Psychopaths

Andre Kirchoff

Valery Fabrikant

“I know how people get what they want. They shoot a lot of people.”

Victims:

4 killed/1 wounded

Duration of rampage:

August 24, 1992 (mass murder)

Location:

Montreal, Quebec

Weapons:

Snub-nosed Smith & Wesson .38-calibre pistol, semi-automatic Meb pistol, semi-automatic Bersa pistol

Self-Entitlement

On a cold December day in 1979, a diminutive balding man shuffled into the Department of Mechanical Engineering at Montreal’s Concordia University. In a deep Slavic monotone, he introduced himself as Valery Fabrikant, and asked to see the chair of the department about applying for a position. Though he was undeniably awkward, behind the lenses of his Coke-bottle glasses his eyes showed a cold intelligence. When Fabrikant was informed that it was university policy to not conduct job interviews without first scheduling an appointment or checking the applicant’s background, he returned every day until the chair of mechanical engineering finally agreed to speak with him. Sitting down with T.S. Sankar, a specialist in solid mechanics, Fabrikant explained that he was a Jewish dissident from Minsk who had fled the Soviet Union, where he had once been an associate professor and the author of numerous scientific publications. Furthermore, he had been once been a student of a scientist whom Sankar profoundly respected. By the end of the interview, Sankar was impressed enough to offer Fabrikant a $7,000-per-year position as his research assistant. He began work on December 20, 1979. If Sankar had bothered to check the thirty-nine-year-old applicant’s credentials or references, he might have thought twice about hiring him. Though Fabrikant’s record in academia was exceptional, he had lied about being a political refugee. Instead, the enigmatic doctor had been fired from numerous positions in the U.S.S.R. due to severe behavioural misconduct.

Shortly after obtaining his position at Concordia, Fabrikant became embittered that the Soviet Union was dragging its feet in sending him a few thousand dollars he had inherited from his late father. In response, he sent a letter to the Canadian Ministry of External Affairs calling for the immediate suspension of grain exports to the U.S.S.R. Here was a man who seriously believed that he could single-handedly disrupt trade between Canada and the Soviet Union in order to hasten the transfer of his inheritance. This was merely the beginning of Valery Fabrikant’s deadly delusions.

When his application was shot down by the University of Calgary in 1981, he travelled to an academic conference solely to belittle the professor who had signed his rejection letter. Fabrikant also wrote angry dismissals to the editors of academic journals who, according to standard practice, had questioned his “ingenious” work. Dr. Sankar received several complaints regarding his colleague’s bizarre behaviour, but ignored them, viewing the world of academia as a necessary haven for brilliant eccentrics. Furthermore, Fabrikant had published a total of twenty-five papers in less than four years — more than double the standard output for his field. As chair of the department, Sankar appeared as co-author on every one. Perhaps this is why he used the department’s research grants to fund the created position of research associate for Fabrikant in 1980, increasing his annual salary to $12,000; then the $23,250-per-year “research assistant professor” in 1982. In Sankar’s eyes, his inclusion as a co-author on Fabrikant’s publications was simply a standard way for his colleague to repay his generosity. For the narcissistic Fabrikant, it was “academic prostitution.”