Real Food (18 page)

Authors: Nina Planck

Harvest is different on industrial and traditional farms, too. Industrial peaches and plums taste nothing like local ones

in season, in large measure because they're underripe. Industrial fruits cannot be picked ripe; they would never survive the

journey, often thousands of miles, to the supermarket. Industrial tomatoes are picked "hard green" and ripened artificially

with ethylene gas. They never develop the complex flavor or luscious texture of a tomato that ripens naturally, with just

the right combination of acids and sugars, like a balanced wine.

Another difference between industrial and ecological produce is postharvest treatment and packaging. Most treatments are designed

to make produce look fresh longer. But is it still fresh? En route to shops, produce is irradiated to kill bacteria such as

E. coli

and extend its shelf life. Irradiated strawberries can still

look

fresh after three weeks, long after an untreated berry would have spoiled. That certainly helps the supermarket produce manager,

but irradiation destroys vitamins, and with every day it sits on the shelf, the berry is less tasty and nutritious. According

to Public Citizen, irradiation also produces new compounds called alkylcyclobutanones, which are linked to cancer and genetic

damage in rat and human cells. Groceries, meanwhile, promote irradiation as a public health measure. But I don't want sterilized

food; I want food that's clean in the first place— and still alive.

How "baby" salad leaves got trendy is one of my favorite industrial produce stories. First, supermarkets offered washed leaves

as a convenience to cooks. (By the way, the history of laborsaving devices in the American kitchen is not encouraging, and

I doubt that people who are too busy to wash lettuce enjoy more leisure than I do.) But the prewashed cut leaves turned brown

too quickly, so growers started to sell small, whole leaves, which lasted longer because they weren't cut.

This convenience to industrial lettuce growers, produce wholesalers, and supermarkets was presented as a gourmet delight—

baby spinach!— but to me, it's simply immature and tasteless. Nor am I a fan of "micro" greens— and they seem to be getting

younger all the time. I saw "infant" arugula on a fancy menu recently, but I prefer mine all grown up.

Adding injury to insult, cut salad leaves are often packed in Modified Atmosphere Packaging (MAP). After the leaves are washed

in chlorine, they're put in bags with less oxygen and extra carbon dioxide. The result is lettuce that still looks fresh ten

days to a month later.

3

Unfortunately, MAP lettuce contains fewer vitamins C and E and antioxidants. Any cut lettuce loses nutrients quickly, but,

as with irradiated berries, MAP lettuce still looks fresh after ten days, while untreated lettuce has withered and turned

brown— a sure sign that it's past its peak and thus unsellable.

Let's return, briefly, to the unpleasant topic of pesticides. Of all the unsavory aspects of industrial produce, pesticides,

though invisible, are probably the most dangerous. "The fact that spreading billions of pounds of toxic pesticides throughout

the environment each year results in extensive harm should not be surprising," writes Monica Moore in

Fatal Harvest: The Tragedy

of Industrial Agriculture,

a book of photos of industrial and ecological farms. "Yet somehow it remains not just surprising, but eternally so. This never-ending

lack of awareness of the true scale of damage keeps people from challenging assumptions that societies benefit more than they

lose from . . . dependence on pesticides."

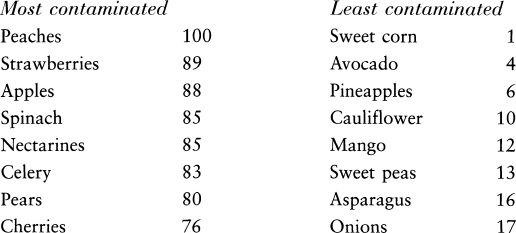

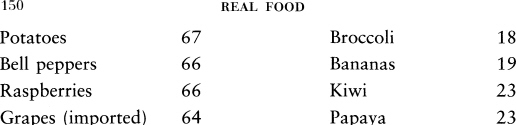

THE MOST CONTAMINATED PRODUCE— AND THE LEAST

Between 1992 and 2001, the USD A tested forty-six fruits and vegetables for pesticide residue. Using this data, the Environmental

Working Group published a list of the least and most contaminated produce. A score of 1 represents the least pesticide residue,

100 the most.

Pesticides are bad news. Organophosphates and methyl carbamates, widely used insecticides, can cause acute poisoning, with

symptoms including headache, dizziness, fatigue, diarrhea, vomiting, sweating, and stomach pain. Severe poisoning brings convulsions,

breathing difficulty, coma, and death. Paraquat, a powerful herbicide, damages the skin, eyes, mouth, nose, and throat; it

can destroy lung tissue and cause liver and kidney failure.

Chronic and long-term effects of pesticides include cancer, infertility, and hormone disruption. According to the EPA, 170

pesticides are possible, probable, or known human carcinogens.

4

The common weed killer 2,4-D is linked to non-Hodgkins lymphoma, and lindane (in lice shampoo) is linked to aplastic anemia,

lymphoma, and breast cancer. DBCP (a nematode killer) and 2,4-D reduce fertility. The herbicide atrazine is an endocrine disruptor,

as is the infamous organochlorine DDT. Though it is now banned in the United States, DDT still lingers in the environment.

We've gone too far. Songbirds are missing, frogs are sterile, and our bodies may already bear the signs of misadventures with

powerful poisons. Farmers and their children have higher rates of cancer and birth defects. All these chemicals were designed

to kill, after all. One way to reduce your exposure to such nasty things is to eat produce raised with organic or other ecological

methods. But what does

organic

mean? And when does it matter?

I Learn How to Answer the Question:

Are You Organic?

WHEN WE FIRST SOLD at farmers' markets in 1980, they were brand-new to the Washington, D.C, area and pretty new in other American

cities, too. New York City's fabled Greenmarket had opened only a few years before, in 1976. People were just getting used

to having farmers set up shop in suburbs and cities. It was all new to us farmers, too, of course, but we did our best— even

us nine-year-olds. Pictures of me at our motley stand from the early years reveal in embarrassing detail how much we had to

learn about display and marketing. We did explain that producer-only farmers' markets (as they're known in our world) were

for local farmers to sell homegrown foods, but

local foods

was not yet in the lingo or understood to be a good thing.

The word

organic

was very much in vogue, however. We heard the same question over and over:

are you organic?

We stumbled over various answers, most of them probably beginning like this: "No, but . . . " This reply, as you might imagine,

failed to satisfy. First, it sounds defensive. Second, some customers, quite reasonably, were seeking organic produce certified

by an independent party, not verbal assurances from a barefoot farm kid.

We felt stuck. We couldn't— and wouldn't— use the word

organic

because we were not certified organic by the state of Virginia, but people wanted to know how we grew our vegetables. One

day at the Arlington farmers' market, I was typically flummoxed, when a friendly customer made what must have been an obvious

suggestion: that we describe our methods on signs, something like NO PESTICIDES or OUR CHICKENS RUN FREE ON GRASS. Excited,

I went home with this idea, which my mother took up with typical editorial intensity, and now our sign boxes are brimming

with information.

We had always used ecological methods, such as mulching to keep weeds down, and we grew most crops without any pesticides,

but when we first started farming, we also used some chemicals. We sprayed the weed killer Roundup on pernicious Johnson grass,

herbicides on corn, and fungicides on melons (melon leaves prefer dry weather, but Virginia is humid). Soon we gave up all

those poisons, but I can still smell the metal cupboard where we kept them. Next time you find yourself in a garden supply

store, go to the chemical aisle, and you'll know the dreadful odor I mean.

How much should you worry about the chemicals on produce? Allow me to answer in a leisurely way. When I was little, we ate

a lot of industrial produce. In the summer, of course, we ate our own vegetables, but in the winter we bought large bags of

industrial fruits and vegetables at Magruder's, the family-owned, local chain famous for good prices. Every day, we ate a

large green salad, a fruit salad, or both. My mother insisted.

These days, apart from the occasional mango or avocado, I buy local produce from the farmers' market all year. There are many

organic growers, but less than half of my produce is certified organic. I should buy more organic and ecological produce,

but for various reasons, I don't. Certain items, like ecological apples and pears, are scarce, and with the huge quantity

of produce I eat, price is a factor. Happily, the non-organic growers I know are well shy of industrial. Still, I do miss

eating our own vegetables— all well-chosen varieties, grown on mineral-rich soil with strictly ecological methods.

If you can't find or afford ecological produce,

eat plenty of fresh

fruits and vegetables anyway.

You may be sure that most studies showing the benefits of diets rich in fruits and vegetables were done on industrial produce.

It is sensible to wash industrial produce, but peeling is a tough call. Most of the pesticides are found in, or just under,

the peel. So are the vitamins and antioxidants. I simply don't know which is the lesser evil.

When I'm deciding how to spend my food money, I use one other rule of thumb:

the higher up the food chain, the more important

ecological methods are.

Thus I spend good money on grass-fed and pastured meat, poultry, dairy, and eggs, but I am less fussy about fruits and vegetables.

That's because chemicals accumulate at the top of the food chain, especially in fatty tissue. If there is pesticide residue

in, say, a stick of industrial butter, it comes from the many bushels of industrial corn and grain the cow ate.

National organic standards implemented in 2002 made some small organic farmers feel threatened by large-scale organic farming.

There is no reason to worry. The new organic rules, if somewhat weak in places, put the spotlight on clean food, and that's

valuable.

Organic

means food was produced without synthetic fertilizer, antibiotics, hormones, pesticides, genetically engineered ingredients,

and irradiation. In shops, where the consumer is one or more steps removed from the farmer, the organic label is a legal guarantee.

I admire organic farmers, large and small; they're committed to clean methods and willing to subject their farms to independent

scrutiny. But many of us— farmers and eaters alike— don't need the organic label. Farmers like my parents, who sell at farmers'

markets or to chefs, can explain directly to buyers why the food is superior to industrial produce. Moreover, many farmers

use ecological methods that may even exceed the organic standards. For example, they promote healthy plants by adding major

nutrients such as calcium, trace elements from sea water, and beneficial microbes to the soil. Cattle farmers raise beef on

grass, which yields more nutritious beef than feeding cattle organic grain. But the organic standards don't specify a grass

diet. It is up to farmers raising grass-fed beef to tell their story, and that is exactly what they are doing, just as we

told our story at farmers' markets twenty-five years ago.

WHEATLAND VEGETABLE FARMS

LOUDOUN COUNTY, VIRGINIA

Our thirty-five acres of vegetables, melons, small fruits, flowers, and herbs are grown without herbicides, insecticides,

or fungicides. Since 1980 we have used ground limestone, compost, cover crops, mulches, and a nontoxic, seawater-based foliar

fertilizer as our only sources of plant nutrition. Each season we hire college students to help us seed, transplant, mulch,

irrigate, pick, load, and sell our crops at twelve producer-only farmers' markets.

— Chip and Susan Planck

We sorely need more research on the nutritional value of industrial and ecological produce. With healthy soil, ecological

produce should contain more vitamins, minerals, and antioxidants. At the University of California, Alyson Mitchell compared

vitamin C and healthy polyphenols in strawberries, corn, and marionberries (a type of blackberry) grown with organic, sustainable,

or conventional methods.

5

The organic and sustainable methods consistently produced higher levels of both nutrients. Unsprayed marionberries and corn

had 50 to 58 percent more bitter-tasting polyphenols than conventional produce.