Real Food (22 page)

Authors: Nina Planck

Once the facts were in on stearic acid, did the experts tell us that the saturated fat in beef and chocolate were good for

the heart? No. According to the International Food Information Council, "In light of the findings about stearic acid, some

researchers recommend no longer grouping it with other saturated fats."

11

In other words, they proposed to

redefine

saturated fats rather than admit that some saturated fats don't raise cholesterol.

Diabetes is a risk factor for heart disease, and for some time, diabetics were prescribed a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet

of fruit, bread, pasta, and nonfat dairy foods. Now (sensibly) there is more emphasis on protein, but saturated fats are still

taboo. The American Diabetes Association says that monounsaturated fats are best, polyunsaturated oils second-best, and saturated

fats to be avoided.

Dr. Diana Schwarzbein, whose specialty is endocrine and metabolic diseases, disagrees. She found that type 2 diabetics got

worse

on a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet. Faithful to her dietary prescriptions, her patients gained weight, their cholesterol

rose, and they required more insulin, not less. Frustrated, Schwarzbein decided to experiment. When she added a little fat

and protein to the menu, results were excellent. Her patients lost weight and had more energy. Their blood sugar and cholesterol

fell. To her surprise, the best results were in the patients who " cheated"— they ate saturated fats and cholesterol in "real

mayonnaise, real cheese, real eggs, and steak every day," she writes. In

The

Schwarzbein Principle,

she describes "The Myth of Saturated Fat": "Many studies . . . vilify saturated fats . . . My clinical experience with thousands

of people has shown that eating saturated fats is not the culprit! On the contrary . . . patients who have increased consumption

of saturated fats (as well as all other good fats) have improved their cholesterol profiles, decreased blood pressure, and

lost body fat, thereby reducing their risk of heart disease."

My own (admittedly unscientific) experience has helped convince me that saturated fats don't cause unhealthy cholesterol.

As I learned more, I conducted a tiny, unintentional experiment. Gradually, I ate more saturated fat in foods like cream,

chocolate, and coconut, until I was eating them every day— as I still do. After eating this way for several years, my cholesterol,

HDL, LDL, triglycerides, and other signs of cardiovascular health are off-the-charts healthy by the standards of the National

Cholesterol Education Program. Indeed, the more saturated fat I eat, the better the numbers look. Yet, by the logic of the

cholesterol theory, I'm doing some important things wrong, and some part of me expects the numbers to look worse. But they

never do.

The story is— of course— not so simple. I also do other things the experts call heart-healthy: I exercise, I don't smoke,

and I eat more than my share of fruit, vegetables, olive oil, fish, dark chocolate, walnuts, and wine. I don't eat trans fats

or refined vegetable oils, and I steer clear of sugar and white flour.

Mine is a balanced diet, to be sure, and the reader (or cardiologist) who favors moderation in all things might consider moderation

its chief virtue. Perhaps. But I routinely eat more saturated fat than experts advise. They would not recommend eating two

eggs with butter for breakfast, coconut curry for lunch, and cream in my cocoa. The medical literature has a label for people

like me:

exceptions

to the rule.

If saturated fats raise cholesterol, and I eat saturated fats but my cholesterol is fine, I am a "nonresponder." Or it could

be that the rule is flawed.

Advice on fats is evolving. In 2004, the

American Journal of

Clinical Nutrition

published a striking article. The authors called our understanding of saturated fats in particular "fragmented and biased"

because research on fats had been so limited. "The approach of many mainstream investigators . . . has been narrowly focused

to produce and evaluate evidence in support of the hypothesis that dietary saturated fat elevates LDL," the authors wrote.

"The evidence is not strong."

12

They noted that saturated fats were "disappearing" from the food supply and asked, "Should the steps to decrease saturated

fats to as low as agriculturally possible not wait until evidence clearly indicates which amounts and types of saturated fats

are optimal?"

13

Accustomed as we are to hyped headlines about miracle foods and superdrugs, this query about fats may seem innocent. Hardly.

Go back and read that paragraph again. Given the conservative style of scientific literature and the heft of the conventional

wisdom against saturated fats, for a prestigious journal to comment in this way is radical.

One year later, as if to answer the call for more research, along came a study of twenty-eight thousand middle-aged men and

women in Malmo, Sweden.

14

Researchers looked for links between fats and mortality from heart disease and from all causes. "No deteriorating effects

of high saturated fat intake were observed for either sex for any cause of death," they wrote. "Current dietary guidelines

concerning fat intake are thus not supported by our observational results."

How much evidence do you need? That's up to you. But if you still fear that traditional saturated fats are trouble, my hunch

is that in the next few years, more evidence in favor of butter will come your way.

IN FASHION TERMS, fats are like a string of pearls— they go with everything. The modern habit of eating chicken breasts and

other lean cuts trimmed of all offending fat is new, an aberration in three million years of human history. Most people never

ate protein without fat for the simple reason that in nature, protein and fat go together. In animals, fat and muscle are

attached.

Eating the fat along with the protein is also frugal and efficient. Traditionally, hunters and farmers ate the whole animal,

including the skin, extra fatty bits, bone marrow, brain, and rich organ meats. Contemporary human hunters, like carnivores,

go for the organs and fatty parts first. Moreover, when times are good— that is, when there is plenty of food— hunters may

even leave the muscle behind for scavengers. Vitamins and other nutrients in the fats and organs are simply more valuable

than the lean protein.

Above all, eating protein with fat makes nutritional sense, because all food, and protein in particular, requires fat for

proper digestion. As we saw earlier with "rabbit starvation," without fat in the diet, digestion fails and you starve, but

not for lack of calories.

What is true of meat is true of all fat-and-protein pairs: they go together. Consider, for example, two near-perfect foods:

eggs and milk. Both foods are a complete nutritional package, designed for a growing organism's exclusive nutrition, and must

contain everything the body needs to assimilate the nutrients they contain. Thus the fats in the egg yolk aid digestion of

the protein in the white, and lecithin in the yolk aids metabolism of its cholesterol. The butterfat in milk facilitates protein

digestion, and saturated fat in particular is required to absorb the calcium. Calcium, in turn, requires vitamins A and D

to be properly assimilated, and they are found only in the butterfat. Finally, vitamin A is required for production of bile

salts that enable the body to digest protein. Without the butterfat, then, you don't get the best of the protein, fat-soluble

vitamins, or calcium from milk. That's why I don't eat, and cannot recommend, egg white omelets and skim milk. They are low-quality,

incomplete foods.

FATS GO WITH EVERYTHING

In each classic pair, fats help the body assimilate, use, or convert essential nutrients.

Fat and Protein

Roast chicken (with the skin)

Eggs (with the yolks)

Fat and Vitamins

Vitamins A, D, E, and K are fat-soluble; eat them with fat

Fat and Beta-Carotene

Buttered carrots

Collards with fatback

Spinach salad with bacon

Flank steak with arugula

Beef with broccoli

Saturated Fat and Omega-3 Fats

Fish with butter or cream sauce

Saturated Fat and Calcium

Whole milk

Yogurt, cheese, and sour cream made from whole milk

Without fats, even vegetables are less nutritious. Brightly colored vegetables are rich in antioxidant carotenoids. They go

better with butter. In 2004, Iowa State University researchers who compared people eating salads with traditional or fat-free

dressings found those shunning fat failed to absorb lycopene and beta-carotene, powerful antioxidants that boost immunity

and fight cancer and heart disease. "Fat is necessary for the carotenoids to reach the absorptive intestinal walls," said

the lead researcher, Wendy White. Lycopene is found in tomatoes and beta-carotene in orange, yellow, and green vegetables.

For vegans, who must rely entirely on vegetables for vitamin A, dressing salad with a traditional fat is even more critical.

Recall that true vitamin A is found only in animal foods ( especially butter, eggs, fish, and liver). The body

can

make its own vitamin A from the beta-carotene in carrots, but the conversion is costly (it requires fats and bile salts made

from cholesterol) and uncertain. Babies, children, diabetics, and those with thyroid disorders make vitamin A with difficulty.

Thus a person eating a strict vegan diet risks vitamin A deficiency. As Hindus and other traditional vegetarian groups know,

butter and eggs are vital ingredients in vegetarian cooking.

Last but not least, the chemistry of fats can explain the long tradition of serving fish with butter and cream. Saturated

fats are required to assimilate omega-3 fats, and they make omega-3 fats go farther in the body. That's the solid nutritional

logic behind the delicious combinations of lobster with melted butter and Dover sole with butter sauce.

IN 1971, AN ITALIAN INTERNIST in her seventies named Mary Catalano was the only doctor in Buffalo who would deliver babies

at home. At my mother's final prenatal checkup, Dr. Catalano, who specialized in heart disease, had an unusual question: was

there olive oil at the house? The answer was yes. So, right after I was born, the doctor gently wiped my skin with olive oil.

Now I wish we could ask her why. Olive oil is often used in homemade cosmetics, but I like to think of my rubdown as part

of some long-lost midwifery tradition. Why not credit Dr. Catalano with my love of olive oil?

The queen of vegetable oils, olive oil is the most famous fat in the world, with a long, glorious history in cuisine and special

status in many cultures. Olive oil is one of the first foods Italian babies eat, and one of the last foods offered to the

dying. The evergreen olive tree grows all over the world, from Tunisia to California to Australia, and can still bear fruit

at the grand age of one thousand years. Olive oil is a staple food in Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain, where most of the

world's olive oil is produced. Its flavor is complex and varied— sometimes grassy and peppery, sometimes buttery and smooth.

Olive oil is also very good for you. It is rich in vitamin E and other powerful antioxidants called polyphenols; both nutrients

prevent heart disease and cancer. By preventing oxidation, they also keep the oil itself fresh. Olive oil inhibits platelet

stickiness, lowers blood pressure, and reduces inflammation. Olive oil has a good reputation with cardiologists because it

is 70 percent monounsaturated oleic acid, which lowers LDL.

Olive oil is about 14 percent saturated palmitic acid (also found in palm oil, butter, and beef), which has a neutral or beneficial

effect on cholesterol.

15

Palmitic acid lowers LDL.

16

Olive oil also contains about 10 percent LA, the essential omega-6 fat. But you probably don't need more LA; the industrial

diet contains too much LA from vegetable oils. If you eat corn, safflower, or soybean oil, replace them with olive oil, which

contains plenty of LA.

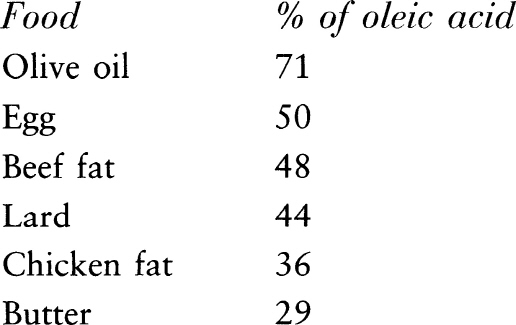

OLEIC ACID IN OLIVE OIL AND ANIMAL FATS

Healthy, delicious, and versatile in the kitchen, olive oil has never fallen out of culinary favor. It is often used cold

in vinaigrettes, pesto, and other raw sauces, which protects its delicate vitamins and antioxidants, but it is also suitable

for cooking at moderate temperatures because it's about 85 percent monounsaturated and saturated. Many "heart-healthy" recipes

call for polyunsaturated vegetable oils such as corn or grapeseed oil for sauteeing, but olive oil is a better choice. According

to

Lancet Oncology,

"The high content of the monounsaturated fat, oleic acid, is important because it is far less susceptible to oxidation than

the polyunsaturated fat, linoleic acid, which predominates in sunflower oil" and other vegetable oils from grains and seeds.

17

A blend of butter and olive oil is even more heat stable because of the butter's saturated fats.