Red Capitalism (18 page)

Authors: Carl Walter,Fraser Howie

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Finance, #General

WHY DOES CHINA HAVE A BOND MARKET?

The fact that banks hold over 70 percent of all bonds highlights the importance of this question. For the group of market reformers surrounding Zhu Rongji and Zhou Xiaochuan, developing the bond market was a basic part of the bank-reform process that began in 1998. A strong bond market would encourage institutions other than banks to hold corporate debt, and risk could be diversified. But if the markets are not wholly opened to the participation of investors not controlled by the state, this cannot happen. The reality is that China’s bond markets has evolved over the past 30 years because the national budget needs to be financed; however, its tax-collecting capacity was, and remains, too weak. If corporate investors could rely on bank lending, the MOF cannot, not if it follows in the model of state treasuries elsewhere in the world. What would a minister of finance be if he could not issue government bonds? What would a modern economy be if it didn’t have a government-bond yield curve to measure risk? The MOF’s growing demand for funds from the early 1980s led to the creation of a narrow market, which reformers 20 years later would seek to broaden.

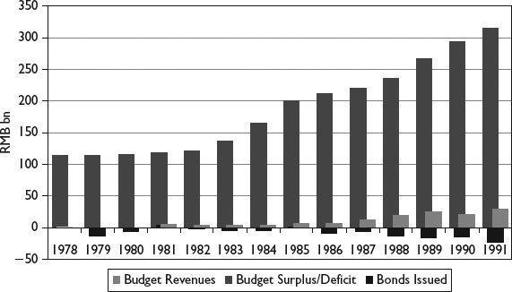

In the early 1980s, markets for securities of any kind did not exist in China. The last bond the country had issued was in 1959 and all knowledge associated with it had long since been lost to the Cultural Revolution. But ambitious national budgets in the early 1980s began to create small deficits (see

Figure 4.1

). Confronting the question of how to deal with increasing amounts of red ink, the idea of issuing bonds was voiced by a courageous person at the MOF. This raised questions about the identity of the investor base and what price to pay them. At the start, only SOEs had money (of course, all borrowed from the banks), so by default, they were compelled to fund the government budget as a political duty. As for price, bond interest was set administratively with reference to the one-year bank-deposit rate set by central bank fiat to which was added a small spread. As the data in

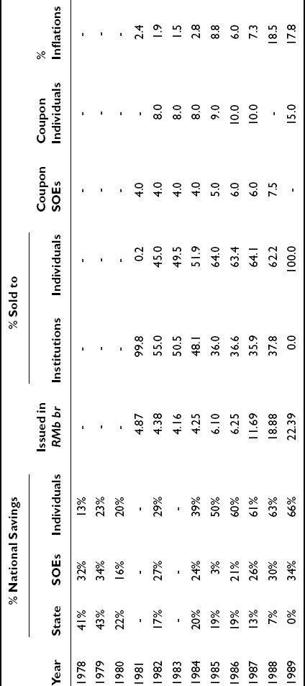

Table 4.1

indicate, individuals received a higher interest rate than SOEs, which reflected both the MOF’s need for third-party funding as well as the demand of retail investors for a reasonable yield. This was a real market situation and the MOF had yet to find a way to minimize its funding costs. As for a secondary market for debt, there was none. SOE investors were forbidden to sell bonds based on logic relating to the MOF’s “face”: selling a bond was seen as a lack of confidence in the state’s creditworthiness.

TABLE 4.1

Composition of national savings and sales of bonds, 1978–1989

Source: Gao Jian: 47–9; China Statistical Yearbook, various

Note: All coupons for maturities of minimum 5 years

FIGURE 4.1

National budget deficits vs. MOF issuance, 1978–1991

Source: China Statistical Yearbook; Wang Nianyong, p. 53

Note: Includes central and local government budgets; excludes maturing bonds rolled over in 1989–1991.

Over the course of the 1980s, successful agricultural reforms and the growth of small enterprises in the cities rapidly enriched the general population. By 1988, nearly two-thirds of all bonds were sold directly to household investors. Then, from 1987, the real market turned as inflation boomed and banks were ordered to stop lending. SOEs and individuals, strapped for cash and seeing yields turning negative, discovered they could sell off their bond portfolios, although at deep discounts, to “speculators”. Suddenly a wholly unregulated over-the-counter (OTC) secondary market sprang into existence just as the craze for shares hit its peak in 1989 and 1990. Here were China’s first (and still only) true markets for equity and debt capital! They were rapidly closed down.

When the political dust from June 4 had settled, China in 1991 had the beginnings of regularized bond and stock markets, but they were ensconced safely inside the walls of the new Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges. The new infrastructure suggested that market reformers had prevailed, but the truth is they had been forced to compromise away the heart of the markets. The two exchanges existed only to provide controlled trading environments where prices and investors could be managed to suit the government’s own interests. For its part, the MOF had also realized by this time that its fund-raising difficulties in part reflected investors’ fear of locking up their cash with no legal way to recover it until their bonds matured. To expand its own funding sources, therefore, from the early 1990s, the MOF began to develop a secondary market on the exchanges.

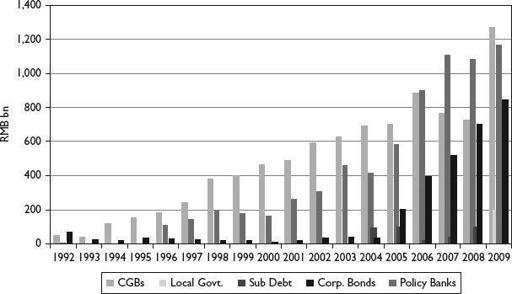

Proper pricing of the bonds remained a problem, however, and it wasn’t until 1994 that the MOF stumbled on a workable combination of underwriting structures and market-based bidding within the strictures of PBOC interest rates that allowed CGB issue amounts to increase (see

Figure 4.2

). The innovator at the MOF, Gao Jian, loves to recount the story of how he created a Dutch auction-based bidding system for a loose group of primary dealers using a Red Tower Mountain cigarette carton to hold their bids.

2

Someone’s smoking habit and an equitable way to distribute the obligation to underwrite government debt largely solved the MOF’s fund-raising difficulties and created the market infrastructure that could be used a decade later.

FIGURE 4.2

Debt issuance by issuer type, 1992–2008

Source: PBOC Financial Stability Report, various; China Bond

Note: The 2007 government bond number excludes the RMB1.55 trillion Special Treasury Bond used indirectly to capitalize China Investment Corporation.

RISK MANAGEMENT

In spite of the success of Gao’s cigarette carton and Dutch auctions, underwriting CGBs, as well as corporate and bank debt, has remained very much a political duty, just as it had been from the beginning. This can be seen from the simple fact that the market did not, and still does not, trade. What is a market without trading? The reason for the lack of liquidity is straightforward: bond prices in the primary market are set below levels that reflect actual demand. Despite its surfaces—record issuance, improved underwriting procedures and issuer disclosure, and even a grudging openness to foreign participation in some areas—it is less a market to raise new capital at competitive prices than a thinly disguised loan market.

This reality is highlighted by the fact that of the primary dealer group of 24 entities, all but two are banks.

3

With the sole exception of the NDRC’s recondite enterprise bonds (

qiyezhai ) that are underwritten by securities companies, banks are the dominant underwriters of all bonds including CGBs, PBOC notes and policy-bank bonds. They underwrite and hold the bonds in their investment accounts until maturity, just like loans. Due to the skewed pricing mechanism in the primary market, banks, like their cousins, the securities companies have not developed the skills to value capital at risk. They do not need to: the PBOC does it for them by fixing the official CGB trading prices in the market as well as the even-more-important one-year bank-deposit rate.

) that are underwritten by securities companies, banks are the dominant underwriters of all bonds including CGBs, PBOC notes and policy-bank bonds. They underwrite and hold the bonds in their investment accounts until maturity, just like loans. Due to the skewed pricing mechanism in the primary market, banks, like their cousins, the securities companies have not developed the skills to value capital at risk. They do not need to: the PBOC does it for them by fixing the official CGB trading prices in the market as well as the even-more-important one-year bank-deposit rate.

PBOC’s perfect yield curves

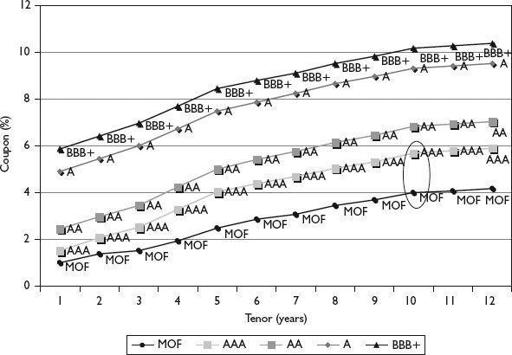

To fully appreciate why there is no “market” in China’s bond markets requires delving into the meaning and practice of bond “yield curves.” These curves show the relative level of interest rates payable on similar securities of different maturities (see

Figure 4.3

for examples) and “cost” means what investors demand for a given level of risk. The interest rates payable by government, or sovereign, issuers are used as the basis of bond-underwriting decisions in all developed markets. This is founded on the theory that countries do not go bankrupt (which is clearly disputable) and that, therefore, they represent the risk-free standard in a given nation’s domestic bond market. In China, the MOF represents the sovereign issuer, the highest credit possible, and the Chinese credit-ratings agencies place the MOF as a unique risk category a level above the AAA (Triple-A) rating represented by, for example, PetroChina. It sounds much better to be a “Quadruple A” than the “Triple A” of, for example, the US Department of Treasury, which one Chinese agency has cheekily assigned it in the Chinese system.

Figure 4.3

shows the PBOC-mandated minimum credit spreads for a variety of enterprise-bond credit ratings over the cost to the MOF. These curves show an ideal world that does not exist: why?

FIGURE 4.3

Mandated minimum spreads over MOF by tenor and credit rating

Source: China Bond, as of October 20, 2009

As in other international markets, the curves are based on the underlying MOF yield curve; for example, the minimum 10-year AAA-to-MOF spread is circled.

4

The trouble in China, however, is that the MOF yield curve is disregarded in favor of the PBOC’s bank interest rates on loans. It is disregarded because it does not truly exist, as is explained below. The PBOC-mandated one-year loan and deposit rates used by banks are shown in

Figure 4.4

.