Red Capitalism (13 page)

Authors: Carl Walter,Fraser Howie

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Finance, #General

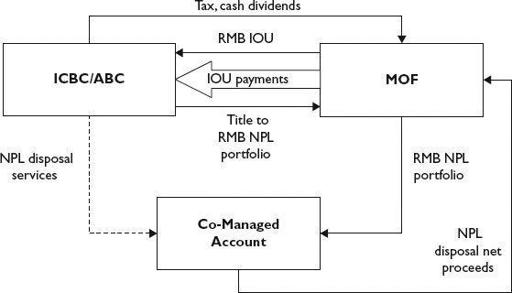

FIGURE 3.6

NPL restructuring for ICBC and ABC, 2005 and 2007

The case of ABC, too, is a pure example of this same MOF approach. Some 80 percent—RMB665.1 billion (US$97.5 billion)—of its NPLs was replaced on a full book-value basis by an unfunded MOF IOU.

6

As with ICBC, the NPL hole on its balance sheet was replaced with a piece of paper conveying the MOF’s vague promise to pay “in following years”, according to the related footnote in its annual financial statement. For ICBC’s receivable, this period is five years; for ABC, it is 15.

On the plus side, this receivable had the advantage of being a direct MOF obligation and relieved the banks of any problem-loan liabilities. Moreover, since ICBC and ABC did not receive cash, excess liquidity did not become a problem. These were the advantages to this approach, but there were also disadvantages.

The details of the underlying transactions for the two banks show that this approach is another instance of pushing problems off into the distant future. Actual title to the problem loans was transferred to the “co-managed” account with the MOF. The banks were authorized by the MOF to provide NPL disposal services. But what exactly is this MOF IOU? It may represent the obligation of the Ministry itself, but, notwithstanding the fact that the MOF represents the sovereign in debt issuance, does its IOU represent a direct obligation of the Chinese government? It would have been a far cleaner break had the MOF simply issued a bond, funding the AMCs directly from the proceeds and using cash to acquire the NPLs. There would have been no need for the PBOC to extend credit at all. That was how the United States Department of Treasury funded the Resolution Trust Corporation during the savings-and-loan crisis.

The approach would have cleaned up the banks completely and the liability would have been indisputably with that department with taxing authority. To have done so, however, the MOF would have had to include the required debt issues in its national budget and received the approval of the National People’s Congress. An unfunded IOU, in contrast, is entirely “off the balance sheet” (

biaowai ) and would only have been approved as a part of the overall bank-restructuring plan approved by the State Council. Indeed, it is possible that the use of IOUs did not even require State Council approval, as these instruments are purely unfunded contingent liabilities. Contingent liabilities are not included, at least publicly, in the national budget, or anywhere else for that matter.

) and would only have been approved as a part of the overall bank-restructuring plan approved by the State Council. Indeed, it is possible that the use of IOUs did not even require State Council approval, as these instruments are purely unfunded contingent liabilities. Contingent liabilities are not included, at least publicly, in the national budget, or anywhere else for that matter.

Then, of course, repayment of its IOUs does not rely on the national budget: it turns out that the banks themselves would be the sole source of cash for funding these payments. Footnotes in the ICBC’s audited financial statements and the ABC IPO prospectus indicate that IOU repayment would come from recoveries on problem loans, bank dividends, bank tax receipts and the sale of bank shares. In other words, the banks would be indirectly paying themselves back over “the following years” since it is entirely unlikely that the MOF would sell (or be allowed to sell) any of its holdings in the banks. Since such funding sources represent future payment streams, it appears that the co-managed funds simply hold the two banks’ NPLs on a consignment basis; they are a convenient parking lot. Given the experience of the AMCs in problem-loan recovery (see below), there is little likelihood that either bank could do much better. The establishment of the Beijing Financial Asset Exchange in early 2010 is highly suggestive of how the banks will dispose of the bad loans in those co-managed accounts. The shareholders of this new exchange, which is located in the heart of the Beijing financial district, include Cinda Investment, Everbright Bank and the Beijing Equity Exchange. Its stated mission is to dispose of non-performing loans by means of an auction process. Perhaps this exchange will lead the disposal process for the two banks. But what entities have the financial capacity to acquire large NPL portfolios and who will take the inevitable write-down? In the end, the MOF will have to issue a bond to cover the net remainder of both of its IOUs or else extend their maturities. Other than avoiding a discussion with the National People’s Congress, it is entirely unclear exactly what is gained by taking this approach.

All of this simply serves to focus the light on the one practical source of repayment: bank dividends. This takes the story right back to bank dividend policies noted in Chapter 2. As will be discussed in regard to CIC in the next chapter, the Ministry of Finance’s arrangement has significant disadvantages, even compared with the far-from-perfect PBOC model.

“Bad bank” performance and its implications

By the end of 2006, BOC, CCB and ICBC had all completed their IPOs and the AMCs shortly thereafter had finished their workouts of their NPL portfolios. Given the weight of the AMCs on each bank’s balance sheet, the question must be asked: how well did these bad banks perform their task? As of 2005, even after the second round of spin-offs, the Big 4 and the second-tier banks still had more than RMB1.3 trillion (US$158 billion) of bad loans on their books. The total of the first two rounds at full face value, together with those remaining as of FY2005, amounted to RMB4.3 trillion. The AMCs were funded by obligations totaling RMB2.7 trillion (US$330 billion), as shown in

Table 3.4

. These liabilities were all designed, even if poorly, to be repaid by cash generated from loan recoveries. Obviously, as the first portfolio of RMB1.4 billion and parts of the second group of portfolios were acquired at face value, repayment was an impossibility from the start. From their first day of operation, the AMCs were technically bankrupt, and practically little different from the “co-managed accounts” now used by the MOF.

At the end of 2006, when more than 80 percent of the first batch of problem loans had been worked out, recovery rates were reportedly around 20 percent—hardly enough to pay back the interest on the various bonds and loans. While recoveries from the second, largely “commercial,” batch suggest a higher rate, industry sources suggest that actual recoveries lagged the prices paid. As 2009 approached and passed, the Party was faced with the problem of how to write off losses that may have amounted to 80 percent of AMC asset portfolios, or about RMB1.5 trillion. But losses could easily have been even greater than that and even long-term industry participants are unsure just what this figure might be.

With some 12,000 staff, the AMCs had their own operating expenses, including interest expense on their borrowed funds. An estimate of operating losses

exclusive of any loan write-offs

is shown in

Table 3.5

. The table uses loan recoveries as a source of operating revenue, an incorrect accounting treatment. But reports indicate that, indeed, the AMCs did use recoveries to make interest payments on their obligations to the PBOC and the banks. Had they not, the banks would have been forced to make provisions against the AMC bonds on their books or the MOF would have had to make the interest payments. There is no indication that this happened. For the sake of arriving at an estimated recovery, figures used in

Table 3.5

are assumed to be 20 percent for loans acquired at full face value and 35 percent for loans acquired through an auction, where the AMCs are assumed to have paid 30 percent. Operating expenses are based on 10 percent of NPL disposals, as stipulated by the MOF.

TABLE 3.5

AMC estimated income statement, 1998–2008

Source: Caijing , May 12, 2008; 77–80 and November 24, 2008; 60–62

, May 12, 2008; 77–80 and November 24, 2008; 60–62

Note: US dollar values: RMB 8.28/US$1.00

| RMB billion | ||

| 1st Round: 1999–2003 | FY2003 | US$ billion |

| Total acquisitions | 1,393.9 | 168.4 |

| Disposals to 2008 | 1,156.6 | 139.7 |

| Recovered, assume 20% | 231.3 | 27.9 |

| less: | ||

| Interest expense on PBOC loans/AMC bonds, 1999–2003 | 190.0 | 22.9 |

| Operating expense, assume half of MOF target 10% of disposals | 57.9 | 7.0 |

| Total operating expense | 247.9 | 29.9 |

| Pre-tax gain/loss | −16.6 | −2.0 |

| Registered capital | 40.0 | 4.8 |

| Retained earnings | −16.6 | −2.0 |

| Accumulated write-offs—Round 1 | −925.3 | −111.8 |

| 2nd Round: 2004–2005 | FY2005 | US$ billion |

| Total acquistions—face value | 1,639.7 | 198.1 |

| Total acquistions—auction value, assume 30% | 491.1 | 59.3 |

| NPLs remaining from Round 1 | 237.9 | 28.6 |

| Assumed disposals—100% | 1,639.7 | 198.1 |

| Recovered on auction NPLs, assume 35% | 171.9 | 20.8 |

| Recovered, Round 1 remainders, assume 10% | 23.7 | 2.9 |

| Total recoveries | 195.6 | 23.6 |

| less: | ||

| Interest expense on PBOC loans/AMC bonds, 2004–2005 | 95.0 | 11.5 |

| Operating expense, assume half of MOF target 10% of disposals | 82.0 | 9.9 |

| Total operating expense | 177.0 | 21.4 |

| Pre-tax gain/loss | 18.7 | 2.3 |

| Registered capital | 40.0 | 4.8 |

| Retained earnings | −2.1 | −0.3 |

| Accumulated write-offs—Round 2 | −533.2 | −64.4 |

| Write-offs − Round 1 + Round 2 | −1,458.5 | −176.1 |