Red Capitalism (31 page)

Authors: Carl Walter,Fraser Howie

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Finance, #General

China Telecom: God’s work by Goldman Sachs

How did China go from having small-scale companies that banks would hardly look at to ones raising billions of dollars in New York in just 10 years? If there is a single reason, it is the persistent enthusiasm for the China story among international money managers combined with their willingness to put vast amounts of money down on it. Their response to the tiny (and bankrupt) Brilliance China US$80 million IPO in 1992 was just as wild as that for China Telecom’s US$4.2 billion IPO in 1997, but the scale of the two companies and the money couldn’t have been more different. International markets introduced Chinese companies to world-class investment bankers, lawyers and accountants and brought their legal and financial technologies—the entire panoply of corporate finance, legal and accounting concepts and treatments that underpin international financial markets—to bear on China’s SOE-reform effort. What happened when aggressive and highly motivated investment bankers and lawyers interacted with government officials at all levels up to and including the State Council altered the course of China’s economic and political history and is the subject of a different book.

This technology transfer greatly strengthened Beijing’s control over the money-raising process, but, strangely enough, in the end weakened the government by strengthening its companies. In 1993, at the start of China’s IPO fever, Beijing was only one of many government entities owning companies competing for the right to raise capital overseas. There was a bureaucratic process at the center of which was the newly established China Securities Regulatory Commission. This heavily lobbied agency screened the listing applications of all local governments and central ministries to come up with an approved list of candidates for which foreign investment banks were allowed to compete for IPO mandates (see

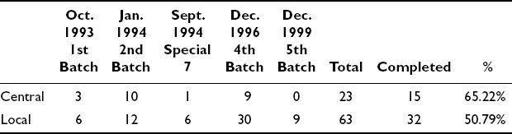

Table 6.5

).

TABLE 6.5

Ownership of listing candidates for overseas IPOs

The early batches included what were then, in fact, China’s best enterprises (for example, First Auto Works, Tsingtao Beer and Shandong Power). None, with the exception of the beer company, had any international brand recognition. The truth is that no one outside of China had ever heard of these companies, knew what they did, or where they were located: China’s SOEs were completely virgin territory for the world’s investment banks. Had anyone ever heard of Beiren Printing, Dongfeng Auto or Panzhihua Steel? Not only were these companies unknown, there were not many of them. By the time calls went out for the fourth and fifth batches, provincial governments came up empty-handed; there simply were very few companies with the economic scale and profitability required for raising international capital. The fourth batch consisted largely of highway and other so-called infrastructure companies, while the fifth batch introduced farmland into the mix. Even Wall Street bankers could not find a way to list what was not even a working farm.

The fact of the matter was that there were few good IPO candidates. Enterprises owned by the central government had enjoyed access to the best financial and policy support since 1979 and this accounts for their reasonably high IPO completion rates. Even so, for the period from 1993 to 1999, they accounted for only one-third of the total of 86 candidates. There were very few that could, even with the best financial advice, meet the requirements of even the most enthusiastic international money managers and only 51 percent of the candidate companies succeeded in listing overseas. By 1996, China’s effort to use stock-market listings to reform its SOEs seemed to have hit the wall. Then came the IPO of China Telecom (now known as China Mobile).

In October 1997, and despite the evolving Asian Financial Crisis, China Mobile (HK) Co. Ltd. completed its dual New York/Hong Kong IPO, raising US$4.5 billion—some 25 times the average size of the 47 overseas-listed companies that had gone before. This kind of money made everyone sit up and pay attention: underwriting fees alone were said to be over US$200 million. If China was, in fact, full of small companies, as the earlier international and domestic listings show, then where had this one come from? The answer is simple, yet complicated: China Mobile represented the consolidation of provincially owned and run industrial assets into what is now commonly called a “National Champion.” This transaction demonstrated to Beijing how it could overcome the regional fragmentation of its industrial sector and, with huge amounts of cash raised internationally, create powerful companies with national markets.

The creation of such new companies out of the grist of the old SOEs would have been impossible without the legal concepts and financial constructs of international finance and corporate law that are the foundation of all modern corporations and the capitalist system itself. In fact, while the capital raised was important in building today’s China, the most important thing of all was the organizational concept that permitted true centralization of ownership and control. The New China of the twenty-first century is a creation of the Goldman Sachs and Linklaters & Paines of the world, just as surely as the Cultural Revolution flowed from Chairman Mao’s Little Red Book.

In the absence of new listing candidates and in the midst of the ongoing technological revolution in the US, Goldman Sachs aggressively lobbied Beijing using the very simple but powerful idea of creating a truly national telecommunications company. Such a company, it was argued, could raise sufficient capital to develop into a leading global telecommunications technology company. The ideas had already been used for the so-called Red Chips that were briefly all the rage among investment bankers in early 1997. Instead of creating holding companies owned by single municipal governments that held its breweries, ice-cream plants, auto companies and, in the famous instance of Beijing Enterprise, the Badaling section of the Great Wall of China, why not acquire and merge provincial telecom entities into a single company owned by the central government?

Given the strong centrifugal forces in the country, this required real political will and power that the imperious Minister of Posts and Telecommunications (MPT), Wu Jichuan, could supply in full. It also required the support of a central government that saw economic scale as a critically important building block to international competitiveness and that was also comfortable with the legal enforceability of shareholder rights (at least its own) in Western courts. China Mobile’s wildly successful IPO catalyzed a series of blockbuster transactions that put Beijing front and center in the world’s capital markets. If there is a single reason why the world is in awe of China’s economic miracle today, it is because international bankers have worked so well to build its image so that minority stakes in its companies could be sold at high prices, with the Party and its friends and families profiting handsomely. The China Mobile transaction was the first big step in this direction.

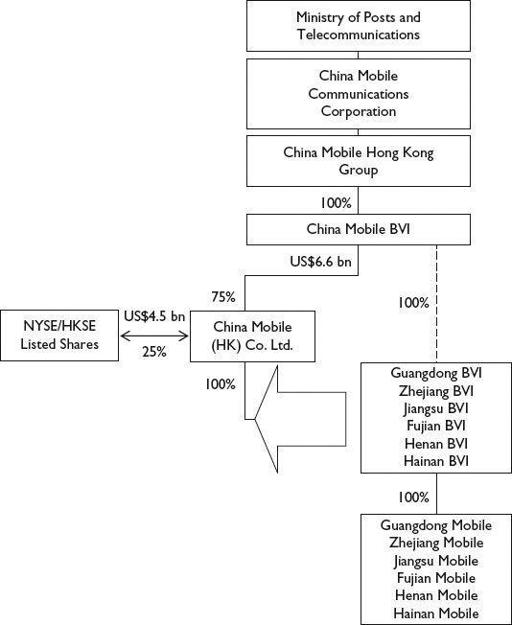

How this historic US$4.5 billion IPO was put together is shown in

Figure 6.2

. Simply put, a series of shell companies were created under the MPT, the most important of which was China Mobile Hong Kong (CMHK). CMHK was the company that sold its shares to international investors, listed on the New York and Hong Kong stock exchanges, and used the capital plus bank loans to buy

from its own parent

, China Mobile (British Virgin Islands) Ltd. (CM BVI), telecom companies operating in six provinces.

FIGURE 6.2

China Mobile’s 1997 IPO structure

The key point that stands out in this transaction is that a subsidiary raised capital to acquire from its parent certain assets by leveraging the

future value

of those same assets as if the entire entity—subsidiary plus parent assets—existed and operated as a real company. The value of the provincial assets, as far as the IPO goes, was based on projected estimates of their future profitability as part of a notional company that was compared to the financial performance of existing national telecoms companies operating elsewhere in the world. In other words, the estimates were based on the assumption that CMHK was already a unitary operating company comparable to international telecom companies elsewhere. This most certainly was not the case in China: prior to its IPO, CMHK was a shell holding company that existed only on the spreadsheets of Goldman’s bankers. The IPO, gave it the capital to acquire six independently operating, but as yet unmerged, subsidiaries. So even at this point, China Mobile could be said to exist only as a paper company, but with a very real bank account.

This was not the IPO of an existing company with a proven management team in place with a strategic plan to expand operations. It would be much closer to the truth to say that this was an IPO of the Ministry of Post and Telecommunications itself! But international investors loved it and two years later, in 2000, a similar transaction was carried out in which CMHK raised a total of $32.8 billion from a combination of share placement ($10.2 billion) and issuance of new shares ($22.6 billion). This massive injection of capital was used to acquire the MPT’s telecom assets in a further seven provinces. As a result of these two transactions, China Mobile had reassembled the MPT’s mobile communications business in 13 of China’s most prosperous provinces in the form of a corporation that replaced a government agency. What happened to the US$37 billion raised after CMBVI was paid is unknowable since it is a so-called private unlisted entity and is not required to make public its financial statements.

The significance of this deal ripples down to this day over a decade later. First, as was the case for the original 86 H-share companies, the government could have simply incorporated each provincial telecom authority (PTA) and sought to do an IPO for each. This would no doubt have greatly benefited local interests and ended up creating many regional companies. The amount of money to be raised in aggregate, however, would in all probability have paled in comparison with China Mobile and there was no certainty that any local firm would have developed a national network. More importantly, the new structure conceptually enabled the potential consolidation of entire industries, making possible the creation of large-scale companies that might someday be globally competitive. Today, China Mobile is the largest mobile-phone operator in the world, with over 300 million subscribers and operating a network that is the envy of operators in developed markets.

Second, and equally important, the money raised was new money, not re-circulated Chinese money from the budget, the banks, or the domestic stock markets. Third, the creation of this structure made possible the raising of further massive amounts of capital simply by injecting new PTAs (or any other “asset”). The valuation of such assets was purely a matter of China’s negotiating skills, flexible valuation methodologies employed by the investment banks and demand in the international capital market. In the case of the acquisition in 2000, foreign investors paid a premium of 40–101 times the projected

future value

of China Mobile Hong Kong’s earnings and cash flow. This was truly pulling capital out of the air! Fourth, this new capital was without doubt paid back into the ultimate Chinese parent, CMCC, giving it vast amounts of new funding independent of budgets or banks. More importantly, the restructuring took what were relatively independent provincial telecom agencies originally invested in by a combination of national and local budgets and allowed China Mobile to monetize them by means of an IPO priced at a huge multiple of the original value. The ability to deploy such capital at once transformed CMCC into a potent force—political as well as economic.

Why wouldn’t Beijing enthusiastically embrace these Western financial techniques when the foreigners were making the Party rich and China seem omnipotent? In the ensuing years, China’s “National Team” was rapidly assembled (see

Table 6.6

) and a similar approach was used to restructure and recapitalize China’s major banks, as described earlier. It need hardly be said that this list includes only central government-controlled companies: Beijing kept the goodies for itself.