Red Capitalism (26 page)

Authors: Carl Walter,Fraser Howie

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Finance, #General

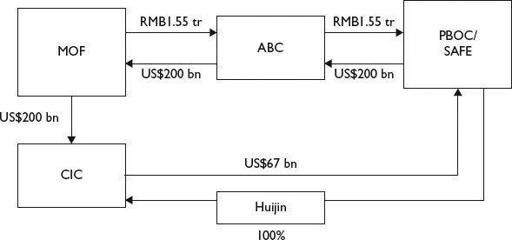

While this seemed like an innovative idea, nothing is without cost, as shown in Step 2 (see

Figure 5.9

). Considering the monetary objective, the MOF had done the PBOC a favor and the transaction could have stopped there. CIC could have been funded through a separate transaction with Huijin using foreign reserves, if the PBOC had been willing to go along. The MOF, however, was out to extract its final pound of flesh and used the RMB acquired from the bond issue to buy US$200 billion from the PBOC/SAFE, again via the services of ABC. The MOF then used these funds to capitalize CIC. Aside from its economic objectives, the institutional effect of this transaction was the restoration of the financial system to the pre-2003 status quo and a further weakening of the PBOC and the market-reform camp. But there was more.

FIGURE 5.9

Step 2: MOF buys US$ from the PBOC to capitalize CIC

After the money had changed hands, CIC for all intents belonged to the MOF. Although it reported directly to the State Council, its top senior management came from the MOF system. This was not necessarily a loss for the reform camp, since CIC was also staffed at senior levels with officials historically associated with market reform. But there was an awkward technical problem arising from the MOF’s arrangement: how would interest be paid on its underlying Special Bonds? The cost involved amounted to around US$10 billion annually. The surprising answer was that CIC would pick up the interest. As the head of CIC dryly commented, the burden was about RMB300 million for each day CIC was open for business. How would CIC, a newly established entity not meant to be a short-term investor, have the immediate cash flow to cover such a huge obligation? The solution to this problem by itself has put an end to further hope of bank reform.

Careful calculation, however, had been given to this solution; it reveals how in 2007 the Party desired to organize China’s financial system and goes to the heart of the PBOC’s loss of institutional clout. Even before CIC received its new capital, the US$200 billion had been budgeted and spent, and only one-third of it related to its advertised mission as a sovereign-wealth fund. The other two-thirds, some US$134 billion, was to be spent on, first, a planned recapitalization of ABC, the CDB and other banks and financial institutions and, second, the outright acquisition of Central Huijin from the PBOC. In one stroke, CIC became China’s financial SASAC.

One might ask why a sovereign-wealth fund would want to own or invest in domestic financial institutions already owned outright by the government: the money would just be going around in circles. But this is exactly what happens “inside the system.” The attractive professional face its management presents internationally is belied by the reality that CIC is, at best, only a part-time sovereign-wealth fund. Its most important role is to serve as the lynchpin of China’s financial system. That system has been restored to one inspired by the old Soviet model centered on the MOF and with a weak central bank.

The MOF is the obvious winner in this domestic game and it is a purely status-quo power. Its victory ultimately has significant negative implications for continued bank reform and can clearly be seen on referring back to

Table 3.3

, which shows the pre- and post-IPO controlling shareholders of China’s major banks. From the very start of bank reform in 1998, the fundamental point of contention between the MOF and the PBOC has been over which entity owns the state banks on behalf of the state. Once reform entered its critical stages in 2003, the plans of Zhou Xiaochuan’s group of reformers began to affect the economic and political interests of the MOF. When Huijin recapitalized CCB and BOC, it did so in a way that established direct economic ownership and, at the same time, used the MOF’s equity interest to write off problem loans; no longer did these two banks “belong” to the MOF empire. In the years after Zhou’s political defeat in 2005, the MOF won back control, starting with the ICBC and continuing through ABC, at least in part because of the PBOC’s difficulties managing its primary responsibilities: inflation and the currency. But this was hardly the only reason.

A contributing part of the PBOC’s political weakness during the crucial year of 2005 was the terminal illness suffered by Vice Premier Huang Ju, who was in charge of the financial sector. In early 2005, Huang stepped aside for treatment and the Premier assumed his portfolio. Consensus politics resumed and the consensus was that Zhou Xiaochuan had overreached. Reform is not about consensus. It was an easy decision that rocked no boats to allow the MOF to retain as equity its 1998 capital contribution in ICBC. So Huijin, after injecting US$15 billion, received only 50 percent of ICBC and the MOF’s 1998 contribution remained. The bureaucratic pendulum had begun its backward swing. By late 2007, with CIC’s outright acquisition of Huijin, the status quo had been fully restored.

The argument in favor of this acquisition was simple: CIC was responsible for the interest on the Special Bonds. Acquiring the banks gave it access to their dividend stream.

11

Since it all belonged to the state anyway, what difference did it make? The fact is, it did make a difference and not just to the bureaucracies involved. If CIC were to acquire Huijin, then SAFE would want its original investment back. The US$67 billion price represented the original net-asset value of its investments in all three banks and a collection of bankrupt securities companies.

12

Since it would be simply a transfer of state-owned assets between state agencies, by government rules, there need be no premium paid. It was just a matter of accounting and the money going from one pocket to the other. The change in “owners,” however, would have a huge impact on reform moving forward.

For CIC, the acquisition worked out very well. According to its first full-year financial report for FY2008, CIC carries at a market value of US$171 billion what it acquired from the PBOC for only US$67 billion. This increased in 2009 to over US$200 billion but, of course, included investments other than Huijin at that point. These investments by Huijin allowed CIC to claim a profit in its first year and so helped deter criticism of its controversial (and loss-making) investments in Blackstone and Morgan Stanley. But there was one small detail that had not been properly considered: three of the Big 4 banks were now internationally listed: the Party was no longer just playing “inside the system.”

CIC squeezes its banks

Beyond its mark-to-market profit on its bank investment portfolio, CIC also relied on the banks for the cash flow to make its interest payments on the MOF bonds, not to mention to pay dividends to MOF that helped it meet its obligations on the IOUs given to ICBC and ABC. The Huijin arrangement designed by the PBOC team placed CIC in a position to receive dividends paid by the banks (see Chapter 7 for further details). This rich source of cash had originally been designed to help offset the unrecoverable loans the PBOC had made to the AMCs in support of bank restructuring. The Huijin arrangement acted as a form of taxation that would, over time, have reduced the PBOC’s credit losses and strengthened its balance sheet.

When CIC acquired Huijin in late 2007, it acquired direct economic control over China’s major banks via their boards of directors and a decisive vote in the matter of their dividends. There would be no intervening levels of ownership, management, and powerful Party secretaries to muddy the issue (as was the case in the SASAC’s state-owned enterprises). Huijin was controlled by the PBOC which, in turn, is controlled by the Finance Leadership Group at the very top of the Party hierarchy. In sum, now MOF was in a position to recommend, if not decide, how much was to be received by . . . itself.

This takes the story full circle back to the bank IPOs. The dividend payout ratio of around 50 percent for all three banks is not necessarily excessive by international standards for banks that are growing at a stable rate and in a normal business environment where bad loans and securities losses are not material. This, however, does not describe the situation faced by the Chinese banks. These banks drive national economic growth by increased lending typically at 20 percent a year and in certain years, such as 2009, much more. But from 2008, Huijin’s new duty would be to pay interest on CIC’s bond obligations to the MOF as well as help the MOF make good on its IOUs. Since the banks are publicly listed and audited by international accounting firms, cash dividends paid by them are transparent to all. To some extent, they might serve as a reliable indicator of how the government thinks about its banks.

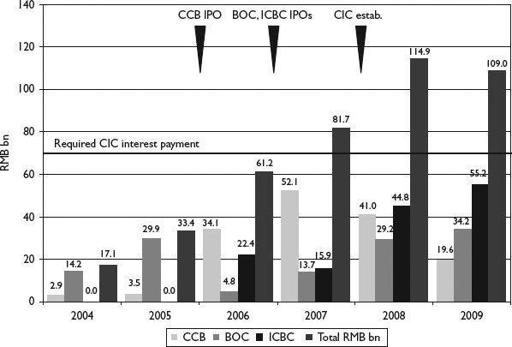

In the early days of restructuring, as NPLs were being spun off to the AMCs and capital rebuilt, asset growth was tightly controlled (see

Figure 3.7

for the years 2001–2005) and capital ratios were rapidly bolstered. After their respective listings, however, lending, profits and dividends for all three banks grew rapidly, particularly after CIC acquired Central Huijin in 2007. From that point, total dividends immediately increased to a level sufficient to cover CIC’s interest obligations, leaving plenty left over to reduce the outstanding restructuring IOU due to ICBC from RMB143 billion (US$18 billion) to RMB62 billion (US$9 billion) (see

Figure 5.10

). Of course, to the extent that CIC and its banks were responsible for making such payments, the national budget was freed of the obligation.

FIGURE 5.10

Big 4 bank IPOs, cash dividends paid and CIC, 2004–2009

Source: Huijin; bank annual audited financial statements

These financial arrangements raise questions about the future path of China’s bank reform. Given the experience of 2009, there is no question but that banks have reverted to their former business model as the Party’s financial utility. But is it really possible that dividend policy is being set to meet the MOF’s own parochial needs? The appearance certainly suggests that the listed banks have become cash cows subsidizing the MOF’s efforts which, among other things, are aimed at sidetracking the institutional influence of the PBOC. Worse yet, it is outrageous that the full amount of cash dividends paid during this period has been funded by the IPOs of state banks (as discussed in Chapter 2). From a very simplistic point of view, international and domestic investors handed over US$42 billion in new capital to the banks and indirectly to the MOF, yet received in those years less than US$8 billion in dividends. Beyond that, is it possible that under pressure to maintain dividends, bank managements might easily be encouraged to increase lending? With fixed spreads over the cost of funding, more lending assures more earnings, higher dividends, better stock price and higher rankings on the

Fortune

Global 500. Then came the economic stimulus package, which provided all the excuse needed to do just that.

Not even a year later, in early 2010, however, the combination of 50 percent dividend payouts and binge lending have created huge challenges for the banks. Most challenged of all must be Bank of China, whose loan portfolio grew nearly 43 percent in 2009 while the other major banks hit levels over 20 percent. Given the high dividend payouts and asset growth, it is hardly surprising that the banks rapidly grew out of their capital base, with BOC and ICBC rapidly approaching capital ratios close to pre-IPO levels (see

Table 5.2

).

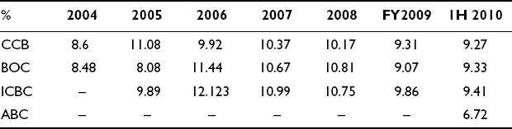

TABLE 5.2

Trends in core capital-adequacy ratio, 2004–1H 2010

Source: bank annual and interim audited reports