Red Capitalism (23 page)

Authors: Carl Walter,Fraser Howie

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Finance, #General

Without question, this market-based outcome has marked a defeat for Chen Yuan’s ambitions for the CDB and represents a major victory for the MOF, which in all probability encouraged his listing ambitions. As discussed below, when China Investment Corporation (CIC) acquired Central Huijin in 2007, it acquired a full 100 percent interest in the CDB. The tables were now turned on Chen Yuan. In the greatest of political ironies, the CDB has now returned to its roots—as a mere sub-department of the MOF—but at what cost to the system?

The People’s Bank of China and the National Development and Reform Commission

In contrast to the CDB’s aspirations and the MOF’s bloodless revenge, the now discredited market-oriented model espoused by reformers is far less eloquently described.

6

It involved the development of direct, market-based, enterprise-financing capabilities based on the decisions of enterprise management. In other words, corporations were to be given a choice between banks and debt markets. Not only that, they were to take responsibility for their decisions for both shareholders and bond investors; in short, the full international capital-markets model. To create this possibility, in 2005, in the midst of collapsed domestic stock markets, the PBOC leveraged a regulatory loop hole defining “corporate bonds”

7

as those with maturities above one year. It used this definition to create a short-term debt product, commercial paper (CP;

duanqi rongziquan ), that quickly became the debt product of choice among SOEs.

), that quickly became the debt product of choice among SOEs.

In 1993, the PBOC had ceded the corporate-debt product to the State Planning Commission (SPC) primarily because issuers would not take responsibility for repayment of bonds on maturity. This created huge difficulties at the time and largely caused the product to be terminated. But in 2005, corporate bonds were a hot product again due to both bank reform and the weak equity markets. Unfortunately, the “enterprise bond” (

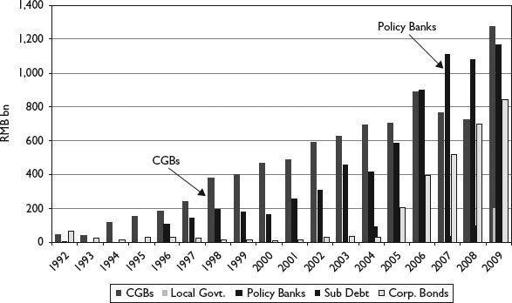

qiyezhai ) market belonged to the SPC’s grandchild, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), with underwriting done only by securities companies regulated by the CSRC. As the volume of issuance in the years up to 2005 illustrate (see

) market belonged to the SPC’s grandchild, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), with underwriting done only by securities companies regulated by the CSRC. As the volume of issuance in the years up to 2005 illustrate (see

Figure 5.2

), neither agency gave much thought to developing this product. From the NDRC’s perspective, a bond was an afterthought. The few projects contained in its planning documents were funded by the national or local budgets or the banks and it could see no need to develop the bond product. From the CSRC’s perspective, bonds represented a zero-sum game with equity products, and the regulator’s avenue to achievement was not fixed-income products or markets.

FIGURE 5.2

Issue volume by product type,1992–2009

Source: PBOC, Financial Stability Report, various

Note: 2007 CGB issuance excludes the RMB1.55 trillion Special Bond

Zhou Xiaochuan provided a detailed analysis of the corporate market’s resultant inadequacies in his famous October 2005 speech excerpted at the start of this chapter.

8

He rightly pointed out that the root cause of the market’s failure to develop was found in the command-economy mentality of the “early days of the transition when the economy was more planned than market-driven.” This comment, historically couched as it was, pointed straight at the NDRC, but the fact is that previous central bank administrations had also done little to promote the bond markets, leaving them to the MOF.

With the support of the Party’s “Nine Articles,” which explicitly called for the development of bond markets, the PBOC drove through this “one year and above” loop hole and created a CP market out of thin air. In 2005, its first year, more than RMB142 billion (US$17 billion) in CP was issued by presumably capital-starved SOEs. This amount tripled in 2008, with growth being driven by a unique ease of issuance: no regulatory approvals were required, only registration. PBOC reformers modeled this process after that used in the US wherein issuers are required to have a credit rating (this takes about three weeks in China), an underwriter (banks, which are not regulated by the CSRC), a prospectus, and a filing with the PBOC. To further ease the government out of any role in the market, in September 2007, the PBOC sponsored the establishment of an industry association—the National Association of Financial Markets Institutional Investors (NAFMII)—to manage things. In contrast to the opaqueness of China’s equity markets, the universe of debt issuers, their financials, approval documents and prospectuses are available for all to see online on the China Bond website.

NAFMII is registered as a non-profit, non-government organization authorized by the PBOC to advise on the development of the debt-capital market, to sponsor new policies and regulations, and to review debt issues. When establishing NAFMII, the PBOC was astute enough to create a governing board including the Who’s Who of China’s banking industry. In its brief existence, the agency has become the regulator in charge of the most rapidly growing segments of the inter-bank debt market, including local-currency risk-management products. Its scope of authority would, of course, exclude the NDRC’s enterprise bonds (

qiyezhai ), as well as financial bonds and subordinated bank debt which, given their direct impact on the sensitive banking sector, remain directly with the PBOC.

), as well as financial bonds and subordinated bank debt which, given their direct impact on the sensitive banking sector, remain directly with the PBOC.

If the commercial paper ploy did not upset the NDRC, the PBOC’s next move did. In April 2008, the PBOC, working through NAFMII, created a three–to–five-year medium-term note (

zhongqi piaoju ). Unlike bonds, which are issued once and remain outstanding until redemption or maturity, MTNs are issued like CP as part of a “program” that allows the issuer, depending on his funding needs, to issue more or less of the securities within a certain overall limit. Perhaps a bit sarcastically, the NAFMII called these securities “non-financial enterprise financing instruments” (

). Unlike bonds, which are issued once and remain outstanding until redemption or maturity, MTNs are issued like CP as part of a “program” that allows the issuer, depending on his funding needs, to issue more or less of the securities within a certain overall limit. Perhaps a bit sarcastically, the NAFMII called these securities “non-financial enterprise financing instruments” (

feijinrong qiye rongzi gongju ) in order to clearly demarcate them from the NDRC’s “enterprise” bonds and the CSRC’s “company” bonds. MTNs, like CP, only require registration with NAFMII.

) in order to clearly demarcate them from the NDRC’s “enterprise” bonds and the CSRC’s “company” bonds. MTNs, like CP, only require registration with NAFMII.

The NDRC, however, did not find the wordplay funny and sought to stop the PBOC and its MTNs by claiming control over the notes which, after all, had tenors of more than one year. The State Council accepted the case, delaying the product’s debut for four months. Later in the year, however, a consensus developed that more debt in the right hands would bolster the swooning stock markets and MTNs were given the go-ahead. In just three months, enterprises raised RMB174 billion (US$26 billion), in new capital and, in 2009, the market grew explosively. By year-end, some RMB608 billion(US$ 89 billion) in new MTNs had been issued. Together with CP, these new instruments accounted for 22 percent of the total capital raised in the fixed-income markets in 2009.

With the defeat of its approach to financial reform in 2005, the PBOC could only push the development of new products in its own space as part of the infrastructure for the future. As

Figure 4.10

shows, CP and MTNs with their shorter maturities brought in new non-state investors, mutual funds and foreign banks. For the first time in China’s bond markets, such investors played a significant role, accounting for 30 percent of short-term corporate-debt holdings. Such small victories can, over time, add up to something important when circumstances change.

LOCAL GOVERNMENTS UNLEASHED

The PBOC’s product innovations provided a solution to financing problems for all sorts of Chinese corporations and not just those commonly thought of as SOEs. It has been 15 years since the last serious reform of China’s system of taxation created a clear split between those taxes belonging to the center and those to the localities. Since that time, SOE reform, the closures of hundreds of failed local financial institutions and the centralization of bank management have greatly reduced the financial resources available to local governments. The shortfall between revenues and expenditures has widened significantly.