Red Capitalism (36 page)

Authors: Carl Walter,Fraser Howie

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Finance, #General

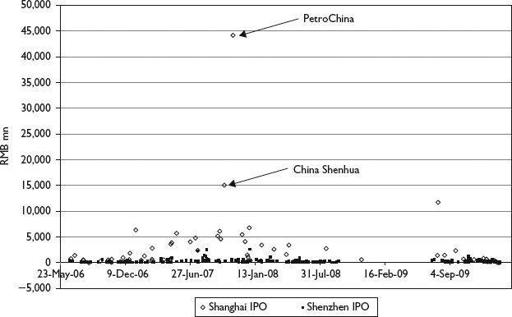

Source: Wind Information and authors’ calculations

But this money, as shown previously, was hardly lost to the state: it had just been given to those state-owned institutions, the group of “family and friends” that had participated in the prearranged lottery. From this, it seems that IPOs function as a means to redistribute capital among state entities with, possibly, some leakage into the hands of retail investors and mutual-fund holders to smooth things out.

The looking-glass culture of these markets creates figures such as the chairman of China Shenhua Energy, Chen Biting, who could say without a trace of irony: “The debut price was within expectations, but I am still a wee bit disappointed.”

7

His lament was that on the first day of Shenhua’s IPO, its shares jumped only 87 percent, leaving just RMB15 billion on the table for his friends. Such generosity characterized the highs of the 2007 stock bubble and Chen was no doubt looking for a doubling of his company’s share price. If he had been running PetroChina, he would have been much happier, it seems. After all, PetroChina’s chairman, Jiang Jiemin, could look his buddies straight in the eyes, knowing that he had delivered for them and the Party that backed them all up. More importantly, he knew that he could now count on their continued support should he need it.

For those in the central

nomenklatura

of the Party, there are no independent institutions, only the Party organization and it is indifferent as to which box does what. On the other hand, just think how relieved the two AMC investors in ICBC’s Shanghai IPO must have felt, knowing they had made enough quick money to pay interest on the PBOC and bank bonds.

Whose hot money?: The trading market

The stock market money-machine works best when IPO prices are cheap and there is huge liquidity in the trading market. This environment drives up the prices of “strategic” investments locked up in the hands of the state investor pool. As is the case in the IPO market, this money does not come from retail investors, as the state would have us believe. From roughly 1995 until the present day, the Chinese secondary markets have been dominated by institutional traders; that is, SOEs and state agencies. Their investment decisions move the market index. While much of the evidence is anecdotal, it has been estimated that anywhere up to 20 percent of corporate profits came from stock trading in 2007. The authors themselves once received a call from a recently listed company asking for advice on how to set up an equity trading desk now that management had some cash in hand. Given the ability to achieve a return greater than the bank deposit rate and the ease with which trading can be disguised, why wouldn’t a corporate treasurer look to make some easy money while the market is running hot?

Based though it is on sparse public information,

Table 7.8

provides a rough breakdown by types of investors in Chinese A-shares at the end of 2006, just as the market was beginning its historic boom. The market reforms of 2005 notwithstanding, shares owned in various ways by the original state investors remain locked up. As a result, the tradable market capitalization is a known figure and at FY2006 totaled US$405 billion. The figure for domestic mutual funds is published quarterly. The retail number is based on the assumption that half of retail investors invest through mutual funds and half invest directly. If accurate, this would mean that retail investors account for nearly 30 percent of the traded market; this is considered to be a high estimate. The size of total Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor (QFII) quotas is publicly known, although the investment mix is not, and the NSSF and insurance companies at this time had known restrictions as to how much they could invest in shares. The assumption in each of these three cases is that 100 percent of their approved quotas was placed in equities; this yields a US$30 billion estimate. Netting all of these knowable fund sources out of the tradable market means that some

60 percent

, or US$245 billion, of the A-share float as of year-end 2006 cannot be linked to identifiable categories of investor.

TABLE 7.8

Investors in China’s stock markets, December 31, 2006

Source: China Economic Quarterly 2007 Q1, p. 11

| US$ billion | % of Total | |

| Total A-share market capitalization | 1,318 | 100.0 |

| Less: capitalization under three-year lock-up | 913 | 69.3 |

| Tradable market capitalization | 405 | 100.0 |

| Total identifiable institutional investors including: | 100 | 24.7 |

| - Domestic funds (actual number) | 60 | 14.8 |

| - QFII (100% of existing total approved quota) | 20 | 4.9 |

| - Securities companies estimate | 10 | 2.5 |

| - NSSF (100% of approved limit) | 5 | 1.2 |

| - Insurance companies (100% of approved limit) | 5 | 1.2 |

| Estimated retail investors | 60 | 14.8 |

| Estimated other investors including: | 245 | 60.5 |

| - State agencies | 115 | 28.4 |

| - State enterprises | 65 | 16.0 |

| - Large-scale private investors | 65 | 16.0 |

Who are these unknown investors that own the majority of the A-share float? Almost certainly, they include many overseas Chinese tycoons who have the wherewithal to evade the prohibition on foreign individual investments in A-shares. More interestingly, during the market ramp-up in 2006, many domestic financial reporters believed the market rumor that China’s army and police forces alone had brought onshore upward of US$120 billion and committed it all to stock investments. While this figure is outlandish, it may have been possible that a smaller amount had been repatriated and invested just as the market began its upward move in 2006, resulting in this much higher value. But there can be no doubt that SOEs and government agencies between them must have held some US$180 billion in

tradable

shares in addition to shares they held subject to a lock-up.

A CASINO OR A SUCCESS, OR BOTH?

It has been nearly two decades since the Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges were established. Why, if they are still regarded as casinos, have they been so successful? How have they come to be seen as beacons of China’s economic reform and attained such central roles in the country’s economic model? The answer is simple: you can make money from them. These markets are driven by liquidity and speculative forces, given the almost-arbitrary business decisions made by companies influenced more by politics than profit. How can this not be the case when companies are the property of the Party and its families?

Such a market may seem daunting to investors from developed markets, but the Chinese are long accustomed to operating in a No Man’s Land of political interference and contradictory signals. None of this stops them from playing or being played by the market: if you buy a share at RMB10 and sell at RMB15, you do make RMB5. Putting money on deposit with banks or playing the bond market is hardly worth the effort; interest rates are set in favor of state borrowers, not lenders, so they do not provide a real return over the rate of inflation.

In China, the only two ways to make this real return are property and the stock markets. Of the two, the stock markets are preferable since they are more flexible than the property market (not that those with the means cannot play both). The investment measure in stocks may be smaller, but liquidity is substantially better than the property market. In contrast to interest rates, the equity market equivalent, the price-to-earnings (PE) ratio, is free to run as high as the market will take it. In the glory days of the Golden Bull Market from 2006 to 2007, the overall Shanghai PE multiple rallied from 15 to nearly 50 times. With that sort of valuation expansion, the upside is very large indeed.

The Chinese market simply doesn’t have natural stock investors: every body is a speculator. Chinese history and bitter experience teach that life is too volatile and uncertain to take the long-term view. The natural result of this is a market dominated by short-term traders, all dreaming of a quick return. The one natural investor is the state itself and it already owns the National Champions. In contrast, ownership in developed markets is far more diversified; large companies simply do not have dominant shareholders owning more than 50 percent of their shares. For example, the largest shareholder of Switzerland’s biggest banking group, UBS, is the Government Investment Company of Singapore, with less than a seven percent holding. Contrast that with Bank of China: even after its IPO the bank’s largest shareholder, Huijin, still controlled 67.5 percent of the bank’s stock.

Since China’s stock markets, which include Hong Kong, are not places that decide corporate control, the pricing of shares carries little weight when thinking about the whole company simply because it is never for sale. This is why there is no true M&A business in China and most definitely none involving non-state or private enterprises acquiring listed SOEs. Instead, market consolidation is driven by government fiat and is accomplished by mixing listed and unlisted assets at arbitrary valuations. This leaves share prices to simply reflect market liquidity and demand at any given time. The high trading volumes in the market are its most misleading characteristic since they give outside observers the impression that it is a proper market. High volumes lend credibility to the idea that prices are sending a signal about the economy or a company’s prospects. In fact, in China, all that the volume represents is excess liquidity.

All markets are driven by a mixture of factors, including liquidity (how much money is in the system); speculation (the belief in making a profit from market volatility); and economic fundamentals (the underlying business prospects and performance of listed companies). Chinese markets are often seen to be decoupled from the actual economic fundamentals of the country. A rough comparison of simple GDP growth and market performance would certainly show minimal correlation between the two. As long as Chinese A-shares ignore economic fundamentals, the market will always be thought of as a casino and too risky for most investors. Chinese investors, however, instinctively know what they are buying because they think the share price is going up, not because the company that issued the shares is having a great quarter or the economy is having a record year.

Much of the effort over the 1990s to develop the markets was aimed at strengthening this fundamental component by creating or introducing more long-term institutional investors, as in developed markets. The entire domestic mutual-fund business was created by the CSRC in the late 1990s with this in mind. The introduction of foreign investors in 2002 via the QFII facility was another step in this direction. The growing volume of company and economic research from local and foreign brokerage houses is all based on the belief that China’s markets are becoming, or will become, more fundamental and driven from the bottom up.

This entire effort is misdirected. It isn’t the absence of equity research that makes the market a casino. It is the absence of genuinely accountable companies subject to market and investor discipline. If the chairmen/CEOs of China’s major companies care little about the SASAC, they care still less about the Shanghai stock exchange or the legion of domestic equity analysts. The CEO knows full well that his company possesses the resources to assure the performance of its own shares. The National Champions dominate China’s stock markets, accounting for the lion’s share of market capitalization, value traded and funds raised.

The growing number of private (non-state) companies listed on Shenzhen’s SME and ChiNext boards is encouraging, but most of these companies, with few exceptions, are tiny in the broader market context. Perhaps investors can look at the SME or ChiNext market and apply the usual investment analysis used in the international markets, but how can an investor look at PetroChina and compare it with ExxonMobil when it is nearly 85 percent controlled by the state and will remain so as long as the Party remains in power? It is the same with China Mobile or China Unicom; can they really be compared with Vodafone, T-Mobile, or BhartiAirtel? The fact that foreign telecommunication providers are barred from China’s domestic market means that China Mobile and China Unicom have a comfortable duopoly. Their privileged positions are simply not subject to the same regulatory or market checks and balances that their global peers face.