Red Capitalism (38 page)

Authors: Carl Walter,Fraser Howie

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Finance, #General

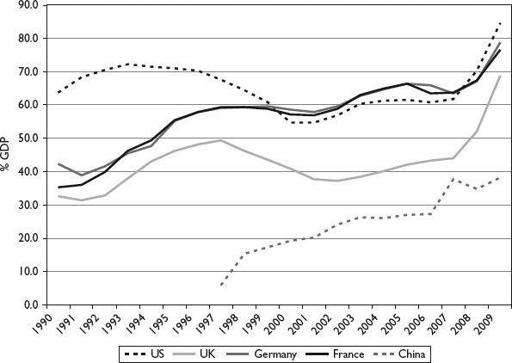

Over the course of the 1990s a fragmented regulatory environment began to take shape, particularly after 1997 when Zhu Rongji moved the government-bond market from the securities exchanges and the CSRC’s oversight to the inter-bank market under the supervision of the PBOC. This was just the beginning. By 2003, seven regulators were responsible for the four major categories of bond products, and equity and commodities had also been parceled out. Each regulator had its favored group of financial institutions or markets—the PBOC had the debt markets; the CSRC and the NDRC had the securities companies and commodities brokers; the MOF had the banks; the CBRC had the trust companies; and the CIRC had insurance companies and private-equity funds. Now even the NDRC is looking for that special vehicle that can give it access to the financial markets. The capital markets are thus divided up into small areas of special interest and members of that group are thereby guaranteed a slice of the action with the help of their own patrons (see

Figure 8.1

).

FIGURE 8.1

Capital-market products by regulator and business beneficiary, FY2009

Source: Wind Information

This is not to say that a single Super Regulator is necessarily the answer to coordination across China’s capital markets. There are good reasons for different regulators for different sectors; stock broking is not banking, and vice versa. The trouble is that in China, the different regulators have over the past few years created so-called “independent kingdoms”; effective coordination across these fiefdoms has been difficult in the apparent absence of strong political leadership.

The lack of a unitary market regulator may have been less important in the 1990s when banks were almost the sole source of capital in the economy. But after the Asian Financial Crisis, Zhu Rongji’s plans to radically restructure the Big 4 banks required a far more integrated approach. Recapitalizing the banks was only one part of a larger plan designed to address the problem of systemic risk. But an integrated solution required the coordination and active support of a wide variety of government agencies including the MOF, the SPC/NDRC, the CSRC and the PBOC. Who would lead? Zhu Rongji was both willing and able to drive financial reform forward until the end of his term in 2003; the momentum that had built up from 1998 carried through until 2005. But, in his absence, when the PBOC sought to institutionalize these reforms in 2005, with itself as the Super Financial Regulator, supporters of the status quo, led by the MOF, pushed back hard enough to stop the consolidation of an integrated approach to financial markets.

As outlined in earlier chapters, when the MOF took back control of the banks from the PBOC, China’s financial system incurred a high cost for its bureaucratic revenge. Foreign investors made a down payment through their participation in IPOs that were, in fact, a prepayment of cash dividends used to make good the interest payments on the MOF’s Special Bond. For their part, China’s major banks became simple channels for this interest, as well as for payments on the special “receivables” the MOF used to restructure Industrial and Commercial Bank of China and Agricultural Bank of China. It would seem that with the MOF’s interest being paid by the banks, the national budget did not need to bear the expense. Perhaps this explains why this Special Bond is no longer recorded in the PBOC’s central depository; after December 31, 2007, these bonds simply disappeared. In addition, the major banks are now in search of another US$42 billion to fill an equivalent gap in their capital created by dividend payments. Even more ungainly, the new sovereign-wealth fund suddenly found itself to be the heart of the entire banking system.

These are the costs to the system when complexity reigns and there is no “Emperor of Finance”. Since 2005, there has been some talk of a unitary financial regulatory body, but there has been little of any substance to emerge except, perhaps, the idea of a “Super Coordinating Commission” that would include all stakeholders. However, just such an agency had existed before, in the late 1980s, and had proved a failure. Who would lead such a commission when even previous coordinating meetings between these regulatory agencies had lapsed into disuse because of “scheduling difficulties”?

BEHIND THE VERMILLION WALLS

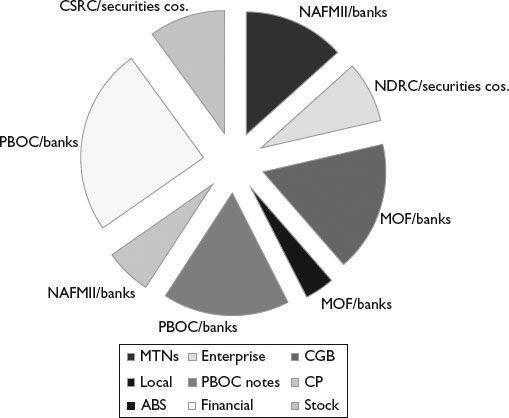

So, without a strong champion for change, the status quo asserted itself; each of the major stakeholders in the system settled back inside its own “courtyard” and pursued their own interests including, especially, seeking access to increasing amounts of bank money. This poorly coordinated chase for funding has rapidly led to significant growth in China’s public-debt burden. The data in

Table 8.1

illustrate the various stakeholders who have contributed to China’s stock of public obligations. For simplicity, the only changes in the projection for 2011 from 2009 are in the estimates of local-government obligations and non-performing loans, the two areas with potentially the greatest variability. These estimates are meant to be conservative and serve simply to show the scale of debt that has already been built up. To be clear, these numbers represent debt obligations; this does not imply that there is no value to the assets or services or other activities that such debt finances. But at a certain point, the cost of these liabilities adds up to a critical mass, becomes burdensome for an economy, and begins to inhibit economic growth. The international standard for such a red line is 60 percent of GDP, beyond which growth may suffer as a government spends more on managing its debt burden than on investing in growth-creating programs.

TABLE 8.1

China public-debt obligations, 2009 and 2011

The table shows that if only the obligations of the MOF (as representative of the sovereign) are used to define central-government debt, then China’s debt ratio is less than 20 percent of GDP, well below the international standard. This is the commonly held view, but it ignores how Beijing has structured its finances over the past decade. The MOF once funded a national budget that included major investments in infrastructure and other fixed assets. Today, such projects are outside the budget and are the responsibility of the policy banks and an aggressive Ministry of Railways (MOR). The obligations of these near-sovereign (if not fully sovereign) entities should be included as part of China’s public debt: would the Party allow any of the policy banks to fail? Such sovereign entities include the MOR, the policy banks, the subordinate debt of the major state banks, as well as any known contingent obligations incurred by the MOF itself (those IOUs plus the 1998 and 2007 Special Bonds). When these obligations are included, public debt almost doubles, to 43 percent.

To this must be added the obligations of local governments, which are without doubt a part of the China sovereign. Beijing historically has been aware of this debt and that it is substantial; a quick look at the finance section of any

China Statistical Yearbook

illustrates this point. The Party, however, is conflicted: Does it really want to know the exact picture? Most successful Party leaders must at some point in their careers serve in the localities. Since local budgets are severely constrained, creative funding solutions—many of which would not withstand outside scrutiny—are the only choice open to the ambitious Party leader. Consequently, the best choice is not to arouse such scrutiny. Local governments comprise more than 8,000 entities at four distinct administrative levels. What is known is that the stock of local debt increased enormously after the announcement of the stimulus package in late 2008. Beijing required local governments to contribute at least two-thirds of the publicly announced total of RMB4 trillion.

This discussion is not meant to suggest that all these figures are exact and correct; it is enough to know the approximate scale of such obligations. In early 2010, Beijing publicly admitted to a figure for total local debt of RMB7.8 trillion—23 percent of GDP and likely to increase over the next few years, if only to complete projects already under way. One estimate of such additional funding needs is RMB4 trillion. There will undoubtedly be additional credit extended but, given the creative financing possibilities offered by the interaction of governments, banks, trust companies and finance companies, no one can know how much. For the purposes of this discussion, it is simply assumed that only RMB4 trillion is spent, so that by 2012, total local debt will be close to RMB12 trillion, or 28 percent of estimated GDP. While no one knows the true amount of local-government debt in China (the banking regulator most certainly does not), if the Hainan and GITIC experiences can be used as reference points, the scale of such debt is as vast as the country it finances.

Not to be forgotten in all of this are the non-performing loans, both current and those obligations yet to be written off from the 1990s. For the upcoming crop of NPLs that will derive from the stimulus-package lending of 2009 and follow-on loans of 2010, a total of about RMB20 trillion (US$2.9 trillion) is assumed.

1

Of this, 20 percent is assumed to have gone to local governments, while the other 80 percent relates to typical SOE or project lending for which new NPLs are estimated, based on a 20 percent rate that begins to be seen in 2011. For the obligations left over from the earlier bank restructuring, the total of RMB3.2 billion is a hard figure derived from audited financial statements and the bank regulator. Together, these old and forecast NPL numbers yield a total of RMB6.4 trillion or over 15 percent of estimated GDP for 2011.

Adding all this up suggests that as of year-end 2009, China’s stock of public debt stood at nearly 76 percent of GDP, well above the international standard. This burden can only increase, given China’s practice of generating a significant portion of GDP growth through fixed-asset investment. Others will arrive at different estimates. The point is simply that in the past few years, China has quickly built up significant levels of public debt, and that is without taking the value of contingent liabilities, such as social security obligations, into consideration.

AN EMPIRE APART

What if this debt buildup is not just the result of a weak hand at the financial tiller? It may also be accurate to say that these increases are the result of the government deliberately leveraging China’s domestic balance sheet to achieve its policy goal of high GDP growth. The economics are simple and well understood: borrow expensive RMB now to build projects the state believes it needs, and make repayment at some point in the distant future using inevitably cheaper RMB.

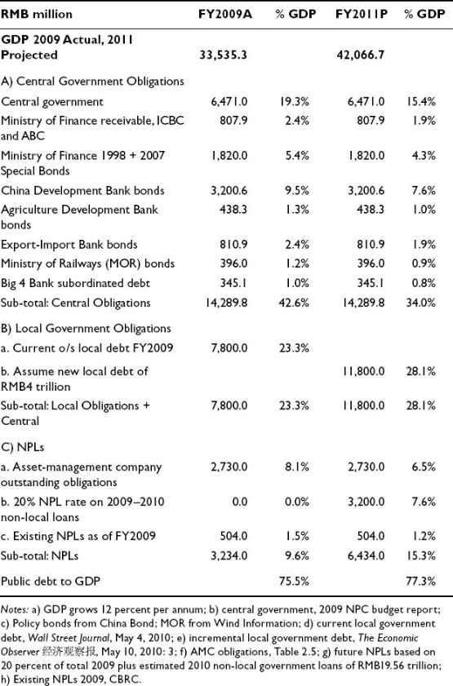

Figure 8.2

shows the growth of outstanding central-government debt, here defined narrowly as that of the MOF plus the three policy banks and the Ministry of Railways only, as against the public debt of four developed economies, including the US. These developed economies have issued debt for a century; at times, as in the case of England in the late 1940s, national debt has been more than 200 percent of GDP. At times, these governments have even defaulted on their debt, as Germany did after World War II. These developed economies have extensive experience in managing public debt, both positive and negative. What is interesting about this chart is how in just a few years, China’s narrowly defined stock of debt seems to be catching up with the levels of developed countries, some with a GDP many times larger than China’s.

FIGURE 8.2

Trends in outstanding public debt: US, Europe and China, 1990–2009