Red Capitalism (35 page)

Authors: Carl Walter,Fraser Howie

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Finance, #General

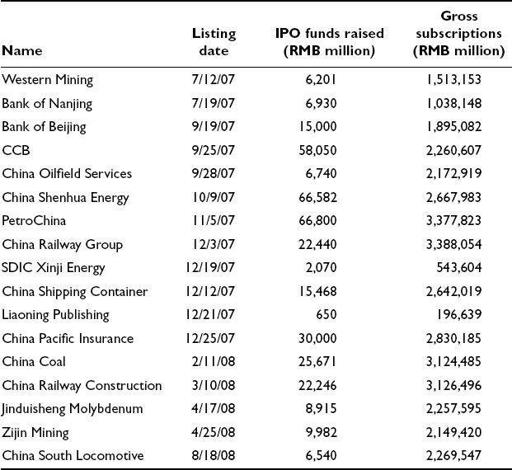

Once the market picked up, however, strategic investors were no longer needed until, that is, the huge Agricultural Bank of China IPO in July 2010, which the government sought to make the world’s largest. It was able to achieve its goal of raising nearly US$9 billion in Shanghai only by relying on a group of 27 strategic investors for 40 percent of an offering that received a very weak reception and was only a little over eight times oversubscribed. This time, 50 percent of strategic allocations were subject to an 18-month lock-up period, indicating again just how weak the reception for the ABC IPO was. By comparison, CCB’s IPO raised US$1 billion less in its Shanghai offering but attracted RMB1.7 trillion (US$210 billion) in lottery applications. Then there was China Railway Group, with some US$400 billion in applications (see

Table 7.6

).

This arrangement served all the important parties well. It meant that the larger deals were about a third sold before they had even been announced, so the downside risk was well covered. But, most importantly, the major investors were able to access huge blocks of otherwise unobtainable shares in the “strategic” group. They were able to hedge these shares, which were by regulation locked up, by massively participating in the open online lottery, in which there was no lock-up period and which, in normal circumstances, guaranteed them eye-popping IPO returns, as discussed in the next section. The lucrative involvement of “family and friends” in an SOE’s IPO ensures that it will receive support from the same group if and when they are called upon: a favor received means a favor returned at a later date.

An example of who such friends were in the case of ABC’s IPO can be seen in

Table 7.5

. The biggest investors included China’s major life-insurance companies and the finance subsidiaries of several National Champions. Further down the list of 173 investors were the proprietary trading accounts of almost the entire list of the SASAC’s National Team as well as asset-management companies and the always profit-oriented Military Weapons Equipment Group Company. These offline friends accounted for 20 percent of the offering. In short, some 60 percent of ABC’s Shanghai listing was supported by the government acting through its National Team. These investors, despite the policy reason for their participation, could not have been heartened by ABC’s modest performance. The first day after listing, its shares rose only one percent, as compared to an average jump of 69 percent even in 2010’s weak market.

TABLE 7.5

Top 20 offline investors in the Agricultural Bank of China A-share IPO

Source: ABC public notice, July 8, 2010

| Name | Value of shares allocated (RMB million) | |

| 1 | Ping An Life Insurance designated accounts | 1,668.6 |

| 2 | CNOOC Finance Co. proprietary account | 1,195.4 |

| 2 | Shengming Life Insurance Co. designated account | 1,195.4 |

| 3 | People’s Insurance Co. managed accounts | 929.3 |

| 4 | Ping An Insurance Co. proprietary account | 896.6 |

| 5 | China Pacific Insurance Co. managed account | 650.5 |

| 6 | Taikang Life Insurance Co. managed accounts | 525.3 |

| 7 | China Power Finance Co. proprietary account | 448.3 |

| 8 | Xinhua Life Insurance designated account | 366.1 |

| 8 | NSSF designated accounts | 335.9 |

| 9 | CITIC Trust designated account | 278.8 |

| 10 | China Aviation Engineering Finance Co. proprietary account | 149.4 |

| 10 | Deutsche Bank QFII account | 149.4 |

| 11 | Jiashi Top 300 Index Fund | 97.6 |

| 12 | Daiya Bay Nuclear Power Finance Co. proprietary account | 92.2 |

| 12 | Red Tower Securities Co. proprietary account | 92.2 |

| 13 | Boshi Stable Value Fund | 83.4 |

| 14 | Yifang Top 50 Fund | 72.2 |

| 15 | Fuguo Tianyi Value Fund | 55.8 |

| 15 | Jingshun Growth Equity Fund | 55.3 |

ABC’s IPO came in the aftermath of the Great Shanghai Bubble of 2007. From June of that year, the market entered the final stage of its heroic bubble, rising 50 percent in four months to nearly 6,100 points. Many people, caught up in the euphoria, believed the index would easily break 10,000 by year-end. During this period, 17 more companies listed on the Shanghai exchange, including PetroChina, China Shenhua Energy and CCB, and none used the formal strategic-investor route (see

Table 7.6

). The reason for this is simple: there was no longer any need; the market was full of liquidity and listing success was guaranteed.

TABLE 7.6

IPOs in the closing days of the Great Shanghai Bubble, 2006–2007

Source: Wind Information and author calculations

This is not to say that these IPOs did not attract the small investor. But in almost any market circumstance, the average deposit required to secure an application was far beyond the reach of any normal retail investor. During the mid-2006 to mid-2007 period, the average online “retail” bid was nearly RMB700,000; in the second half of 2007, when strategic investors were no longer needed, it rose to RMB1.2 million

on average

. During this period, there were more than a million online investors per IPO; PetroChina attracted over four million. So while small investors most certainly came out to help boost the number of applications, they did not account for the bulk of the money put down online: institutions did.

As for the offline tranche, the amounts of money involved could be staggering. For example, in PetroChina’s Shanghai IPO, 484 institutional investors successfully bid for allocations in an offline tranche that accounted for 25 percent of the entire share offer. The smallest successful bid was made by the appliance-maker Haier, which received 2,089 shares and was refunded RMB1.64 million from its lottery deposit. The largest was Ping An Life, which received a total of 119 million shares in a handful of separate accounts and got back RMB93.2 billion (US$11.4 billion) in excess bid deposits. Not far behind was China Life, with over 100 million shares and deposits worth RMB78.5 billion (about US$10 billion) returned. Reviewing the 400-plus names reveals a

Who’s Who

of China’s top financial and industrial companies, including even the Military Weapons Equipment Group Company (

Bingwu Gongsi

) of the People’s Liberation Army.

If one of the original goals of creating stock exchanges was, as stated, to ensure the primacy of a socialist economy overseen by the Party, then China’s experience with stocks has succeeded far beyond any reasonable expectation.

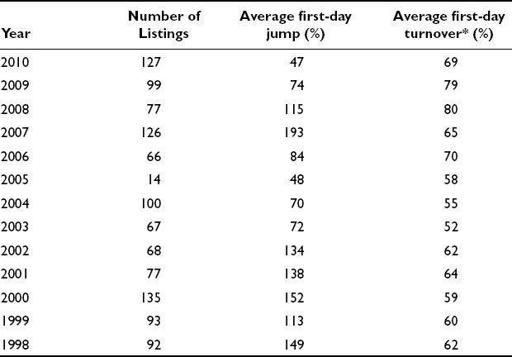

Keeping everyone happy: Primary-market performance

In addition to the lottery arrangements that create mass feeding frenzies, the share valuation mechanism set by the CSRC explains the popularity of IPOs in China. Simply put, prices are knowingly set artificially low while demand is set high, with the result that big price jumps on listing day are virtually guaranteed (see

Table 7.7

). This approach also eliminates underwriting risk so that securities firms need not be concerned that their underwriting fees are so thin. But this all comes at a cost. The pricing process eliminates the need for investors to understand companies and the industries in which they operate to arrive at a judgment as to valuation.

TABLE 7.7

A-share listing-day price performance

Source: Wind Information; author’s calculations; 2010 data through March 31

Note: * represents the amount of shares sold as a percentage of what was allowed to be sold on the first day.

Since the process is dumbed down to a formula, underwriters have never learned how to value companies and price risk. Even worse, the investor population, in whatever category, never became educated as to the values of different companies, the prospects for their shares, or the risks associated with investing. Over time, the result has been that companies became commodities and getting an allocation of shares, any shares, became the sole objective and wildly oversubscribed IPOs were the result. From another angle, what these valuations of China’s National Champions are most certainly not revealing is Chinese management skill, technical innovation, entrepreneurial flair, or the growth of genuine companies. What they do show is the state’s confidence in its own ability that, when push comes to shove, it can manage the market index so that it will go up and the state’s holdings will increase in value. Chinese investors refer to their stock markets as “policy” markets for this very reason: they move on the expectation of government policy changes and not on news of company performance. The fundamental value-creation proposition in China is the government, not its enterprises.

In spite of this, prices play a huge role, although not in valuing the risk related to the business prospects of companies. As mentioned, the CSRC formulas uniformly result in share valuations well below prevailing market demand so that double-digit and triple-digit first-day jumps in prices become par for the course. Put another way, the regulator requires that companies and their underwriters price shares in a completely opposite way to market practice in Western markets. Forced by their ultimate state owner, companies effectively sell their two-yuan shares for one yuan.

From an international perspective, the losses to companies arising from this practice are enormous. As an extreme example, take PetroChina. The company raised RMB67 billion (US$9.2 billion) in its Shanghai IPO and received RMB3.4 trillion (US$462 billion) in subscription deposits. The difference between its actual share price and a market-clearing price based on actual demand is shown in

Figure 7.5

. As indicated, PetroChina’s cheap pricing meant that it had left RMB45 billion (US$6.2 billion) on the table. Not surprisingly, on its listing, PetroChina’s shares jumped nearly 200 percent, giving it, albeit briefly, a market capitalization of more than US$1 trillion. From a developed-market viewpoint, this was a complete crime. It should have been an even bigger crime in the SASAC’s eyes, given the cheap sell-out of state assets. From the company’s viewpoint, an astute chairman would have wondered why he had just sold 10 percent of his company at half the value attributed to it by the secondary market. To put it another way, he had sold US$16.8 billion of stock for just US$8.9 billion. In an international market, he would, no doubt, have fired his investment bankers outright and then been fired by his board.

FIGURE 7.5

Money left on the table