Red Capitalism (22 page)

Authors: Carl Walter,Fraser Howie

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Finance, #General

4

Of course, underwriters are free to set higher interest rates (known as coupons) on enterprise bonds if their issuer clients agree.

5

From January 2004, the cap on maximum interest rates on loans was eliminated, but banks are still subject to a minimum rate charged, which is 90 percent of the PBOC set rate for the relevant tenor.

6

Figures from US Department of Treasury, Office of Debt Management, June 2008.

7

There is, however, now a stock index future product.

8

Foo Choy Peng, “China Economic Rated Top Broker,” Bloomberg, January 13, 1996.

9

The Asian Development Bank and the International Financial Corporation, a part of the World Bank, have been the only foreign issuers in the domestic bond market to date.

10

The inter-bank market in China was established in 1986 as a funding mechanism for banks in which those with surplus funds place them with others needing additional funding in order to balance their books.

11

A small number of bonds remained listed on the Shanghai exchange to enable securities firms to finance themselves through repo transactions. Until recently, banks were excluded from this market. Their reintroduction is largely an effort to merge what has become two separate markets: the exchange-based and the inter-bank.

CHAPTER 5

The Struggle over China’s Bond Markets

“If it doesn’t have access to a stable and sufficient source of capital, the China Development Bank will be unable to operate normally.”

Unnamed staff member, Treasury Department, China Development Bank

January 11, 2010

1

The combination of bank restructuring and the stock market’s collapse from mid-2001 catalyzed dynamic growth in China’s bond markets. This period began with the appointment of Zhou Xiaochuan to the governorship of the PBOC in early 2002. That year, a total of RMB933 billion (US$113 billion) in bonds, largely Chinese government bonds (CGB) and policy-bank bonds, was issued. By 2009 new issuance had nearly tripled, to RMB2.8 trillion (US$350 billion), and included a large chunk of corporate and bank bonds. As of year-end 2009, the total value of China’s outstanding stock of debt securities had reached RMB 17.5 trillion (US$2.6 trillion), with a mix of products that included government bonds (US$841.8 billion), PBOC notes (US$620.6 billion), bank bonds (US$747.1 billion) and a variety of corporate debt (US$354.1 billion) being traded between more than 9,000 institutional investors.

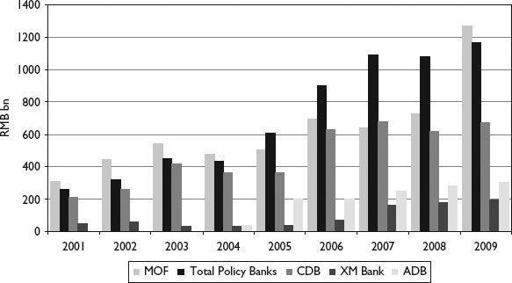

Many issuers struggled to get a piece of this market, none more significant than the China Development Bank (CDB). As the trends in

Figure 4.2

illustrate, the CDB has begun to challenge for the dominant position, becoming, in effect, the country’s second Ministry of Finance. The bank’s RMB620 billion (US$912 billion) in issuance in 2009 was nearly on a par with the MOF’s RMB666.5 billion (excluding savings bonds) and represented nearly 30 percent of the total market. Equally significant, driven by the need to finance the stimulus package, Beijing at last recognized the legitimate funding needs of local governments and allowed certain poor provinces to issue bonds. In addition, all levels of local government made aggressive use of the bond markets, raising RMB423 billion (US$62 billion) via their own enterprises on top of massive levels of bank borrowing.

Far surpassing the CDB and the localities were the PBOC’s efforts to sterilize the creation of new RMB generated by China’s huge inflows of foreign currency. From 2003, as China’s trade surplus began to widen and foreign investors flocked to invest, the PBOC began to issue ever-increasing amounts of short-term notes (and sometimes long-term notes, as we saw in Chapter 3) to control the domestic money supply. This use of a market-based tool to manage the macro-economy was a first in China, but pressures on the PBOC grew to the point that its institutional rival, the MOF, was able to step in and “help out.” A complex series of transactions relating to the establishment of China’s second sovereign-wealth fund revealed a triumphant MOF in control of the very lynchpin of the domestic financial system, once again bringing the story back to the bank dividend policies described earlier.

THE CDB, THE MOF AND THE BIG 4 BANKS

The rapid growth in the China Development Bank’s funding and lending activities coincides with the ascension of the new Party and government leadership in 2003 and the start of a continuing debate about China’s economic development model. During this time, the CDB became the darling of those supporting a return to both a more state-planned economy domestically and a natural-resource-based foreign policy internationally. But understanding the CDB’s position is complicated by the fact that, on the one hand, it represented a challenge to the prevailing banking model sponsored by Zhou while, on the other, it depended on the PBOC for approval of its annual bond-issuance plan. The dramatic increase in its bond issuance during this period may be the result of the PBOC’s antipathy toward the MOF; but the MOF also had its own tactics.

Chen Yuan, the bank’s very ambitious founding chairman, positioned the CDB deliberately as an alternative model to the Big 4 banks. The Big 4, under Zhou Xiaochuan’s reform program, followed a path modeled after their international counterparts, including the deliberate introduction of international banks as strategic investors. As we saw earlier, Chen Yuan was opposed to what he referred to as “that American stuff.” Instead, he proposed to “develop around our own needs and build our own banking system” which, he said, “must provide the capital to meet the needs of our high-growth economy, resolve the various financial bottlenecks of our enterprises and provide a channel for capital for various types of enterprise.”

2

The bank’s investment projects, once included in the national budget, are now independent of it; the CDB can, to a certain extent, determine on its own “commercial” principles what projects to invest in and what not. Nonetheless, its projects are state projects and its obligations are state obligations. The CDB, unlike the Big 4 banks, was established as a ministerial-level entity with quasi-sovereign status reporting directly to the State Council. It is a typical example of an organization, not an institution, built around one man, the son of a powerful revolutionary-era personage. Chen’s father, Chen Yun, was the planner whose famous “Bird Cage” theory provided the ideological foundation for the Special Economic Zones in the 1980s. Political conservatives were able to accept the idea of foreign investment as long as it was “caged” inside these special zones. This powerful political concept has now morphed and provides the inspiration for the distinction between “inside” and “outside” the system. Unless there are bounds imposed by a determined Party leader, as was the case during Zhu Rongji’s era,

3

“princelings” such as Chen Yuan can drive the political and economic process in ways contrary to the national interest, as we will see further in the next chapter. In Chen’s case, the goal has long been to add both an investment bank and a securities company to the CDB portfolio and become China’s first universal bank (and this in spite of his avowed aversion to “American stuff”). If the CDB can be a universal bank, is it any wonder that the Big 4 banks have reacted defensively by wanting to acquire the licenses held by their respective AMCs?

If it had succeeded, the strategy Chen marked out for the CDB would have marked a return of China’s banking system to the pre-reform era and the People’s Construction Bank of China (PCBC). Essentially a division of the MOF, the PCBC provided exactly the same kinds of long-term capital services for the economy as Chen’s CDB. The difference, however, is that the CDB possesses a modern corporate veneer and polished public-relations expertise, as evidenced by its website on which Chen’s old-fashioned sloganeering is pushed into the background. That, however, is not the most important difference. The PCBC was funded by the national budget and it channeled, on behalf of the MOF, the disbursement of interest-free investment funds to SOEs and special infrastructure projects contained in the state plan. But the CDB does not rely on the national budget for funding.

This fact and Chen’s own ambitions created a trap for the CDB. As a policy bank, the CDB funds itself through debt issuance in the markets, and China’s bond markets are fully reliant on the commercial banks and the PBOC for support. Some 72 percent of the CDB’s funding comes from those very banks Chen holds in such low esteem. As

Figure 5.1

illustrates, beginning in 2005, CDB bond issues began to grow rapidly. This growth was approved by the PBOC, whose own position was being challenged by the MOF.

FIGURE 5.1

MOF vs. policy bank bond issuance, 2001–2009

Source: China Bond

Note: 2007 MOF issuance excludes the CIC Special Bond of RMB 1.55 trillion; 2009 MOF issuance excludes RMB200 billion local government bonds.

Since banks are the source of all funds, if this situation had continued, market saturation could have been reached and, from that point, the CDB would have begun to squeeze out the MOF, as

Figure 5.1

indicates. Can one man fight the MOF as well as the Big 4 Banks? The answer is “No” and this is where ambition led Chen Yuan astray.

In addition to pursuing greater business scale, Chen appears to have envied the superficial modernity of the commercial banks. This led him to seek to create China’s first universal bank and to become publicly listed. He was clearly encouraged to pursue this goal and on December 11, 2008, the CDB became a joint-stock corporation, the first step in preparing for an IPO. But why in the world would the State Council seek to make a policy bank—which had been designed to make and hold non-commercial investments in state-designated infrastructure projects—into a commercial entity and then to list it? Chen’s argument was that “commercialization” would not change the bank’s strategy as a development bank:

The lesson we can take is that a first-class bank should not take even the very best Western bank as a standard. We should have an objective international standard . . . expressed as having high-quality assets, the trust of market investors, and an objective, fair and deep understanding of society’s needs and to work to resolve those social needs in order to receive society’s approval.

4

The CDB model, with its emphasis on social-justice issues, threatens the last 15 years of profit-oriented banking reform in China and has already erased the policy-bank reforms of 1994. While Chen’s words and vision may have resonated among the country’s people and top leadership in the wake of the global financial crisis, they found no such resonance in the bond market.

5

The reason for this is simple: the banking regulator had been less than precise in defining the CDB’s new status. After its incorporation, is the CDB still a semi-sovereign policy bank or is it now a commercial bank? From this definition flows the valuation of its outstanding bonds, as well as the pricing for future bond issues. Market pricing will differ depending on the answer and there is as yet no clear answer. It is not just about pricing: if the CDB is a commercial entity, other banks and insurance companies will only be able to invest up to a regulation-imposed limit and the CDB’s days of cheaply funded expansion will rapidly come to an end.

The uncertainty as to the CDB’s exact status is what accounts for its bonds being more actively traded than those of the MOF. Uncertainty is risk and the risk created by Chen’s ambition is by no means small for his investors, the commercial banks. They currently hold an estimated RMB3.2 trillion (US$460 billion) of his old bonds on their balance sheets and even a small 0.5 percent drop in value for them would mean mark-to-market losses of RMB16 billion (US$2.3 billion). Even though they hold CDB debt as investments, the loss of value on such a scale might ultimately require their international auditors to recommend loss provisions and a hit to their income.

In early 2010 as the party reflected on the massive lending binge of 2009, the accepted line became: “We know these projects do not produce cash flow today, but they will prove very useful to China’s development later on.” This describes perfectly the function of lending by policy banks. On the other hand, policy loans in commercial banks are, by definition, NPLs. This was recognized in 1994 when the CDB was established and the Big 4 banks embarked on commercialization. It is now beyond irony that just as China’s hard-built commercial banks have turned themselves into policy banks, the China Development Bank is striding in the opposite direction.