Red Capitalism (29 page)

Authors: Carl Walter,Fraser Howie

Tags: #Business & Economics, #Finance, #General

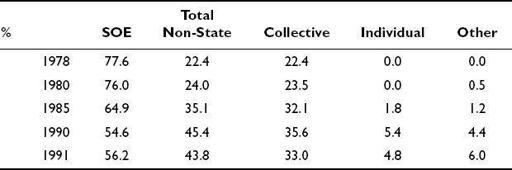

On their surface, China’s stock markets are the biggest in Asia, with many of the world’s largest companies, and more than 120 million separate accounts trading stocks in nearly 1,800 companies. Their capital-raising abilities are the stuff of legend (see

Table 6.1

). According to data from Bloomberg, since January 2006, half of the world’s top 10 IPOs were Chinese companies raising over US$45 billion. It is not uncommon for new issues in Shanghai to be 500 times oversubscribed, with more than US$400 billion pledged for a single offering. The scale of China’s companies since 1990 has increased exponentially. In 1996 the total market capitalization of the top 10 listed companies in Shanghai was US$17.9 billion; by year-end 1999, this was US$25.3 billion and, 10 years later, US$1.063 trillion! Like everything else about China, the simple scale of these offerings and the growth they represent at times seems staggering.

TABLE 6.1

Funds raised by Chinese companies, China and Hong Kong markets

Source: Wind Information and Hong Kong Stock Exchange to September 30, 2010

Note: US$ at prevailing rates; Hong Kong GEM listings not included; No B-share issuance since 2000.

Of course, the scale of the profit involved can also be huge. In 2009, Chinese companies raised some US$100 billion, of which 75 percent was completed in their domestic markets of Shanghai and Shenzhen. Underwriting fees in China are around two percent, suggesting that China’s investment banks (and only the top 10 at best participate in this lucrative business) earned fees totaling US$1.5 billion. This amount, as large as it, pales in comparison to the amount collected in brokerage fees. For example, on a single day, November 27, 2009, A-share trading on the Shanghai and Shenzhen markets reached a historic high of over RMB485 billion (US$70 billion) in value. For a market that doesn’t allow intra-day trading, that turnover is truly impressive—more than double the rest of Asia, including Japan, combined. Brokerage fees for that one day alone totaled around US$210 million, spread between 103 securities companies. With all that money up for grabs (and a clear preference for domestic over foreign markets by Chinese companies) it is no wonder that there is so much noise surrounding China’s stock markets—investment bankers anywhere are hardly known for being self-effacing and China’s are no different.

Observers are also very impressed with the market’s infrastructure. Like the inter-bank debt markets, the mechanics of the stock exchanges are state-of-the-art, with fully electronic trading platforms, efficient settlement and clearing systems and all the obvious metrics such as indices, disclosure, real-time price dissemination and corporate notices. The range of information provided on exchange websites is also impressive and completely accurate, but all of this is only a part of the picture. China’s stock exchanges are not founded on the concept of private companies or private property; they are based solely on the interests of the Party. Consequently, despite the infrastructure, the data and all the money raised, China’s stock markets are a triumph of form over substance. They give the country’s economy the look of modernity, but like the debt-capital markets, the reality is they have failed to develop as a genuine market for the ownership of companies.

The engine at the heart of the debt markets is the valuation of risk and this is missing in China because the Party controls interest rates. Similarly, the heart of a stock market is the valuation of companies and this is also missing in China because the Party controls the ownership of listed companies. Private property is not the central organizing concept of the Chinese economy; rather, the central organizing concept is tied to control and ownership by the Communist Party. Given this basic premise, markets cannot be used as the means to allocate scarce resources and drive economic development. This role belongs to the Party which, to achieve its own ends, actively manipulates both the stock and debt markets. As shown in the previous two chapters, the debt market cycle takes place within a regime of controlled interest rates and suppressed risk valuations that are the corollary to the Party’s control over the allocation of capital. The stock markets, in contrast, are vibrant, but do not trade securities that convey an ownership interest in companies. What these securities do represent is unclear, other than that they have a speculative quality that permits gains and losses from trading and IPOs.

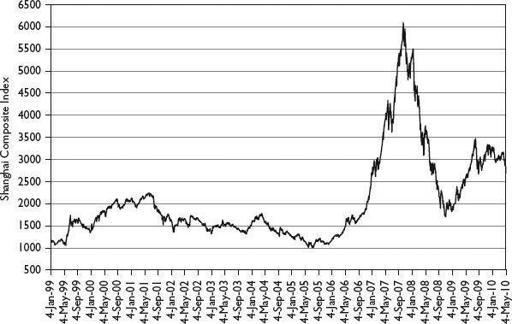

In China, the stock and the real-estate markets have evolved into controlled outlets for surplus capital seeking a real return and, for the most part, this capital is controlled by agencies of the state. Stocks and real estate are the only two arenas in China that, although subject to frequent administrative interference, can produce rates of return greater than inflation. The huge run-up in the Shanghai Index in 2007 is an example of this (see

Figure 6.1

): the significant appreciation of the RMB that year drew in large volumes of “hot money” that was then parked in stocks, drawing the index ever higher. Like developed markets, China’s stock markets operate rationally, but only within a framework shaped by the distorted and biased initial conditions set by the state. Their substance cannot and will not change unless these boundary conditions change. This would require outright and publicly accepted privatization—a highly unlikely prospect in any prognosticator’s near- or medium-term futures.

FIGURE 6.1

Performance of the Shanghai Index, 1999–2009

Source: Wind Information

WHY DOES CHINA HAVE STOCK MARKETS?

Why would China’s government in 1990 of all times decide to create stock markets? The decision to open the Shanghai exchange was made in June 1990, just a year after Tiananmen, and it opened at year-end in the midst of malicious political mudslinging concerning whether the reforms of the 1980s belonged to what are commonly referred to in China as “Mr. Capitalism” or “Mr. Socialism.” The markets were not needed from the viewpoint of capital allocation. Then, as now, the Big 4 banks provided all the funds the state-owned sector could possibly want. The reason for establishing stock markets was not related to political expediency or the capital requirements of SOEs. Rather, Beijing decided to establish stock markets in 1990 largely from an urge to control sources of social unrest and, in part, because of the inability of its SOEs to operate efficiently and competitively. The stock-market solution to both issues was purely fortuitous. If there had not been a small group of people sponsored by Zhu Rongji who had plans for stock markets already drawn up, China today could have been quite different. Moreover, had these people retained authority over market development into the new century, China could have been quite different in yet another way.

“Share fever” and social “unrest”

In the 1980s, China’s stock markets arose for the same reasons as stock markets in Western private economies: small, private and state-owned companies were starved of capital and small household investors were seeking a return. The idea of using shares to raise money sprang up simultaneously in many parts of the country and, given the relaxed political atmosphere of the times, the ideas were allowed to take shape.

3

Despite Shanghai’s raucous claims to be the country’s financial center, there is no argument but that Shenzhen was the catalyst to all that has come after. Its proximity and cultural similarity to Hong Kong were major factors behind this. The key year was 1987, when five Shenzhen SOEs offered shares to the public. Shenzhen Development Bank (SDB), China’s first financial institution (and first major SOE) limited by shares, led off in May and was followed in December by Vanke, now a leading property developer. Their IPOs were undersubscribed and drew no interest. The retail public’s indifference to SDB’s IPO even forced the Party organization in Shenzhen to mobilize its members to buy shares. Despite this support, only 50 percent of its issue was subscribed.

The fact is that after more than 30 years of central planning, near-civil war and state ownership, the understanding of what exactly an equity share was had been lost in the mists of pre-revolution history. Where securities called “shares” existed, investors thought of them as valuable only for the “dividends” paid; people bought them to hold for the cash flow. There was no awareness that shares might appreciate (or depreciate) in value, and so yield up a capital gain (or loss). So the market was understandably tepid for the bank’s IPO and it was also unprepared for events that followed payment of the first dividend in early 1989.

The SDB’s dividend announcement in early 1989 marked a major turning point in China’s economic history and it should be recognized as such. The bank was very generous, awarding its shareholders—largely state and Party investors—a cash dividend of RMB10 per share and a two-for-one stock dividend. In the blink of an eye, those who had bought the bank’s shares in 1988 for about RMB20 enjoyed a profit several times their original investment. Even so, a small number of shareholders failed to claim their stock dividends and the bank followed procedures to auction them off publicly. The story goes that when one individual suddenly appeared at the auction, offered RMB120 per share, and bought the whole lot, people got the point: shares were worth something more than simple face value. As this news spread in Shenzhen, a fire began to blaze. The bank’s shares, as well as the few other stocks available, sky rocketed in wild street trading. SDB’s shares jumped from a year-end price of RMB40 to RMB120 just before June 4, 1989, and despite the political trouble up north, ended the year at RMB90.

Armed with this new insight, China’s retail investors set off a period of “share fever” centering on Shenzhen and gradually extending to Shanghai and other cities such as Chengdu, Wuhan and Shenyang where shares were traded. In the end, Beijing forced local governments to take steps to cool things down. Restrictions eventually took hold, leading to a market collapse in late 1990. Even so, investors had learned the lesson of equity investing: stocks can appreciate. But Beijing had also learned a lesson: stock trading could lead to social unrest. The decision to establish formal stock exchanges was made in the midst of “share fever” in June 1990 and the Shenzhen and Shanghai exchanges opened later the same year.

State-owned enterprise reform via incorporation

Of course, Beijing could simply have forbidden stocks and all associated activity, but it didn’t. The reason for this can be found in a policy debate about the sources of dismal SOE performance. Despite the government’s lavishing of resources and special policies of all kinds on SOEs during the 1980s, China’s emerging private sector had left them in the dust.

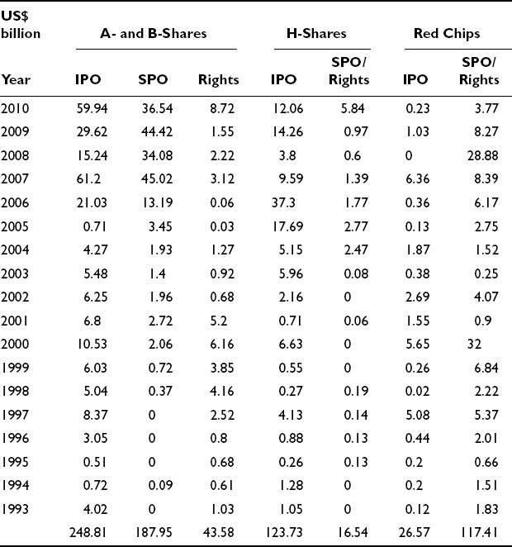

The annual growth rates of private industry exceeded 16 percent as against only seven percent for the state sector (see

Table 6.2

). As a consequence, the private sector had increased its share of industrial output nationally from 22 percent to more than 43 percent during the decade. For the Party, this was simply not acceptable and, in fact, it is still not acceptable. Then (as now) the Party expected the state sector to dominate, and in the late 1980s, it desperately needed to find an effective way to strengthen the sector, if not to stimulate better SOE performance.

TABLE 6.2

Share of total industrial output by ownership

Source: China Statistical Yearbook, various